The Sustainable Active Investing Framework: Simple, But Not Easy

by Wesley Gray, AlphaArchitect

The debate over passive versus active investing is akin to Eagles vs. Cowboys or Coke vs. Pepsi. In short, once our preference for one style over the other is established, it becomes a proven fact or incontrovertible reality in our minds.

This post is not meant to convert a passive investor into an active investor; however, we do explain why we believe some active investing approaches can logically beat passive strategies over a reasonably long time horizon (clearly it won’t work forever). Our framework also helps investors decipher the quantitative “factor zoo,” to determine if data-mining computers have actually identified a sustainble active strategy or a pipe dream.

We cannot overemphasize that identifying sustainable alpha in the market is no cakewalk. More importantly, being smart, having superior stock-picking skills, or amassing an army of PhDs to crunch data is only half of the equation. Even with those tools, you are still only one shark in a tank filled with other sharks. All sharks are smart, all sharks have a MBA or PhD from a fancy school, and all the sharks know how to analyze a company. Maintaining an edge in these shark infested waters is no small feat, and one that only a handful of investors has accomplished.

In order to achieve sustainable success as an active investor, one needs skill, an understanding of human psychology, and an appreciation of market incentives (behavioral finance). We start our journey where mine began: as an aspiring PhD student studying at the University of Chicago. Let the adventure begin…

Into the Lion’s Den: Pitching Market Inefficiency in the Land of Efficient Markets

I entered the University of Chicago Finance PhD program 13 years ago (Fall 2002). It was the beginning of a painful, but highly enlightening journey into the world of advanced finance. For context, the UChicago finance department maintains a rich legacy associated with having established, and successfully defended, the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). PhD students in the department spend their first 2 years in grueling, graduate-level finance courses infused with highly technical mathematics and statistics. The final 2-4 years are dedicated to dissertation research. I would describe these conditions as: “sweatshop factory meets international mathematics competition.” The program was tough.

After surviving my first 2 years of intellectual waterboarding, I needed a break. I took a unique “sabbatical”, and decided to join the United States Marine Corps for 4 years. Long story short: I wanted to serve and I wasn’t getting any younger.

I returned to the PhD program in 2008 to finish my dissertation. My time in the Marines taught me a lot of things, but one lesson stood out from the rest: “Make Bold Moves.” And of course, what is the boldest move one can do at the University of Chicago?

Write research that claims markets aren’t perfectly efficient.

OK…sounds bold…how the heck are we going to show this?

Inefficient Market Mavericks: Value Investors

I wanted to determine if traditional value-investors can “beat the market.” I had been following a value investing strategy with my own account for over 10 years. I was a tried-and-true believer in the Ben Graham mantra: margin of safety. The story that long-term value investing beats the market was compelling, but much of the rhetoric in academic circles, and the research published in top-tier academic journals, suggested otherwise.

The “value” debate was reinvigorated by the famous Fama and French 1992 paper, “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns.” The paper sparked a debate over whether or not the so-called “value premium,” or the large spread in historical returns between cheap stocks and expensive stocks, was due to extra risk or to mispricing. The risk-based argument for the value premium didn’t sit well with me as a Ben Graham aficionado. Graham and Buffett were famous for beating the market over long periods of time by buying cheap stocks. I began digging.

I started collecting data on nearly 4,000 stock picks submitted by top fund experts, asset managers, and value enthusiasts to Joel Greenblatt’s website, ValueInvestorsClub.com. And this wasn’t just any club. Highly selective, screened for quality, and regarded as one of the best sites on the web for market ideas, these members were true heavy hitters in the value investing arena (see appendix for details).

After a year of toil and anguish, I compiled all 4,000+ recommendations into a database so I could conduct a thorough analysis. The results were extremely compelling–there was strong evidence that these “Varsity Value Investors” exhibited significant stock picking skills.

Excited to share my new findings, I eagerly drafted a paper, which included the following abstract:

Figure 1a: “Value investors have stock picking skills.”

I immediately sent my draft dissertation to my advisor, who happened to be the godfather of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Eugene Fama, a strong–if not the strongest–supporter of EMH reviewed my results. The response I received was less than ideal:

Figure 1b: “Your conclusion has to be false.”

I sped down to Dr. Fama’s office to get some clarification. The last thing I wanted was a year’s worth of blood, sweat, and tears to get tossed out the window. I had to know exactly why Dr. Fama disagreed. Sweating profusely, with the prospect of the PhD title slowly slipping away, I asked one of the world’s most famous financial economists, for clarification. Fama responded:

“Listen, the data and analysis are sound, you simply can’t say that, “value investors have stock picking skills,” but instead you need to qualify that statement with, “the sample of value investors we investigated,” have stock picking skills.”

I sat back, relieved. Sounds like I might graduate after all. Prof. Fama was correct: My findings did not suggest that all value investors have skill, merely the sample I was investigating had skill. Crisis averted. I graduated the following year, with my research affirming, at least for me, that markets were not perfectly efficient.

But nagging questions abounded: What gives a certain investor “skill”? What characteristics drive alpha? Why can one active manager (winner) systematically take money from another active manager (loser)?

Enter behavioral finance and “rational” investors.

As I plowed through thousands of stock-picking proposals, one key takeaway was present. These analysts were good. They all had skill. They all were smart. They all made compelling cases that, statistically, outperformed in aggregate. But that couldn’t be the only reason why they outperformed. As I mentioned above, everyone in this market is smart and capable…intellect alone can’t be the driver of superior returns. What enabled these varsity stock pickers to buy low and sell high and why was the Efficient Market Hypothesis not stopping them?

Enter behavioral finance.

John Maynard Keynes, a shrewd observer of financial markets and a successful investor, highlights the paradox that behavioral finance represents. At one point, Keynes was nearly wiped out while speculating on leveraged currencies (despite being a highly successful investor). This downfall led him to share one of the greatest investing mantras of all time:

“Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

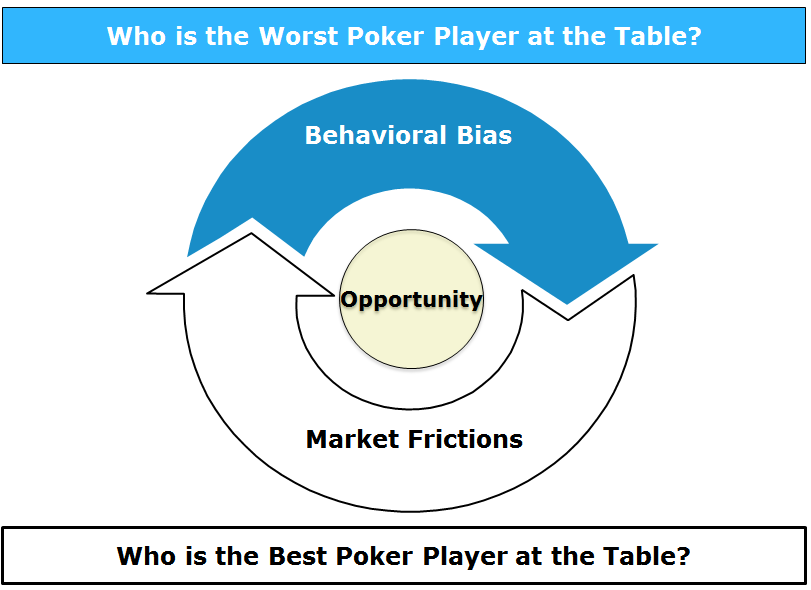

Keynes’ quip highlights two key elements of real world markets that the efficient market hypothesis doesn’t consider: investors can be irrational and arbitrage is risky. In academic parlance, “investors can be irrational” boils down to an understanding of psychology. “Arbitrage is risky” boils down to what academics call “limits to arbitrage”, or market frictions. These two elements–psychology and market frictions–are the building blocks for behavioral finance (depicted in Figure 2, below).

Figure 2: The 2 Pillars of Behavioral Finance

First, let’s discuss limits to arbitrage, more commonly referred to as market frictions. The efficient market hypothesis predicts that prices reflect fundamental value. Why? People are greedy and any mispricings are immediately corrected by those smart, savvy investors that can make a quick profit. But in today’s world of instant information, super computers, and interconnected markets, true arbitrage–profits earned with zero risk after all possible costs–rarely, if ever, exists. Most arbitrage involves some form of cost or risk (risk of buying at the wrong price, risk of paying high transaction costs, liquidity, etc). Let’s look at a simple example:

Arbitraging oranges:

- Oranges in Florida cost $1 each.

- Oranges in California cost $2 each.

- The fundamental value of an orange is $1 (Assumption for the example).

- The EMH suggests arbitrageurs will buy in Florida and sell in California until California oranges cost $1.

But what if it costs $1 to ship oranges from Florida to California? Prices are decidedly not correct–the fundamental value of an orange is $1. But there is no free lunch since the frictional costs are a limit to arbitrage. In short, the smart, savvy arbitrageurs are prevented from exploiting the opportunity (in this case, due to frictional costs).

Next, a discussion of psychology. Newsflash: humans beings are not rational 100% of the time. To any one who has been married, driven without wearing a seat belt, or hit the snooze button on their alarm clock, this should be pretty clear. And the literature from top psychologists is overwhelming for remaining naysayers. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel-prize winning psychologist, and author of New York Times Bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow, tells a story of 2 modes of thinking: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is the “think fast, survive in the jungle” portion of the human brain. When we start to run away from a poisonous snake (even if later on, it turns out to be a stick), you are relying on your trusty System 1. System 2 is the analytic and calculating portion of the brain that is slower, but 100% rational. When you are comparing the costs benefits of refinancing your mortgage, you are likely using System 2.

System 1 keeps us alive in the jungle. System 2 helps us make rational decisions for long-term benefit. Both serve their purpose; however, sometimes one system can muscle onto the turf of the other. When System 1 starts making System 2 decisions, we can get in a lot of trouble. Do any of these sound familiar?

- “That diamond bracelet was so beautiful, I just had to buy it.”

- “Dessert comes free with dinner, of course I had to have some.”

- “Home prices never seem to go down. We gotta buy!”

Unfortunately, the efficiency of System 1 comes with drawbacks–what keeps us alive in the jungle isn’t necessarily what saves us from ourselves in the markets.

Now, let’s combine our irrational investors (System 1 types) with the limits of arbitrage that we discussed above (smart people that simply can’t take advantage of the System 1 types for some reason). Combining the bad behaviors with the limits that smart people run into could be a very compelling strategy indeed.

For example, consider the concept of “noise traders” (think day traders that ignore fundamentals and trade on “gut” – classic System 1 types). These irrational noise traders dislocate prices, but because they are irrational, arbitragers have a hard time pinning down the timing when these System 1 types will make their trades. Thus an element of risk arises when an arbitrageur tries to exploit an irrational noise trader. Brad De Long, Andrei Shleifer, Larry Summers, and Robert Waldmann describe this phenomenon, “Noise Trader Risk in Financial Markets,” in the Journal of Political Economy in 1990.

Here is the abstract from the paper:

We present a simple overlapping generations model of an asset market in which irrational noise traders with erroneous stochastic beliefs both affect prices and earn higher expected returns. The unpredictability of noise traders’ beliefs creates a risk in the price of the asset that deters rational arbitragers from aggressively betting against them. As a result, prices can diverge significantly from fundamental values even in the absence of fundamental risk. Moreover, bearing a disproportionate amount of risk that they themselves create enables noise traders to earn a higher expected return than rational investors do. The model sheds light on a number of financial anomalies, including the excess volatility of asset prices, the mean reversion of stock returns, the underpricing of closed-end mutual funds, and the Mehra-Prescott equity premium puzzle.

Let’s translate this into English:

Day traders mess up prices, but these people are idiots, and you can’t really time the strategy of an idiot, so most smart people don’t even try take advantage of them. Consequently, prices move around a lot more than they should because no one is stopping the idiots. Moreover, since prices move around a lot more, the returns can be higher, so idiots think they are actually good at timing markets, which incentivizes more idiots to do more idiotic things.

This combination of bad behavior and market frictions describes what behavioral finance is all about:

Behavioral bias + market frictions = interesting impacts on market prices.

And while this working definition of behavioral finance may seem simple, clearly, the debate surrounding behavioral finance is far from settled. In one corner, the efficient market clergy claims that behavioral finance is heresy, reserved for those economists who have lost their way from the “truth.” They point to the evidence that active managers can’t beat the market and incorrectly conclude that prices are always efficient as a result.

In the other corner, practitioners that leverage “behavioral bias” suggest that they have an edge because they exploit investors with behavioral bias. Yet, practitioners who make this claim often have terrible performance.

So what is the disconnect?

The disconnect lies in the fact that both sides of the argument fail to assess both the bad behaviors of the market AND the limits to arbitrage. Passive investors assume there are no limits to arbitrage and markets are perfectly efficient. Practitioners who claim to exploit behavioral bias believe they are the smartest poker players at the table, but they ignore the fact there are other smart poker players who have also identified behavioral bias in the marketplace.

Good Investing is like Good Poker: Pick the Right Table

Behavioral finance outlines a framework for being a successful active investor:

- Identify market situations where behavioral bias is driving prices from fundamentals (e.g., identify market opportunity)

- Identify the actions/incentives of the smartest market participants (e.g., identify market competition)

- Find situations where mispricing is high and competition is low

In the context of poker, a similar strategy is critical for success:

- Know the fish at the table (opportunity is high)

- Know the sharks at the table (competition is low)

- Find a table with a lot of fish and few sharks

In Figure 3 below, the graphic outlines the questions we must ask as an active investor in the marketplace.

- Who is the worst poker player at the table?

- Who is the best poker player at the table?

To be successful over the long-haul, an active investor needs to be good at identifying market opportunities created by poor investors, but also skilled at identifying situations where savvy market participants are unable or unwilling to act.

Figure 3: Identifying Opportunity in the Market

Understanding the Worst Poker Players

While stationed in Iraq, I saw stunning displays of poor decision-making. Obviously, in areas where violence could break out at any moment, it was of paramount importance to stay focused on standard operating procedures. But in extreme conditions where temperatures regularly reached over 125 degrees, stressed and sleep-deprived humans can sometimes do irrational things.

In Figure 4, I am situated at a combat checkpoint in Haditha, a village in Al Anbar Province. I am explaining to my Iraqi counterparts how to set up a tactical checkpoint. A quick inspection of the photograph highlights how a stressful environment can make some people do irrational things. My Iraqi friend directly beside me in the photo is wearing a Kevlar helmet, carrying extra ammunition, and has a water source on his gear. These are all rational decisions:

- Kevlar helmets are important because mortar rounds can kill you.

- Rational reaction: wear your Kevlar helmet!

- Ammunition is important because shooting back can save you.

- Rational reaction: carry ammunition!

- Water is important because 125 degree heat can kill you.

- Rational reaction: carry water!

While all of these things sound rational, the Iraqi on the far right isn’t wearing a Kevlar, isn’t carrying extra ammo, and doesn’t have a source of water.

Figure 4: Chaotic Environments + Emotion + Stress = Bad-Decision Making

Is my irrational Iraqi friend abnormal? Not really. All human beings suffer from behavioral bias and these biases are magnified in stressful situations. After all, we’re only human.

Below I laundry list a plethora of biases that can affect investment decisions on the “financial battlefield”:

- Overconfidence (“I’ve been right before…”)

- Optimism (“Markets always go up”)

- Self-attribution bias (I called that stock price increase…)

- Endowment effect (“I have worked with this manager for 25 years, he has to be good”)

- Anchoring (“The market was up 50% last year, I think it will return between 45 and 55% this year.”)

- Availability (“You see the terrible results last quarter? This stock is a total dog!”)

- Framing (“Do you prefer a bond that has a 99% chance of paying its promised yield or one with a 1% chance of default? – hint, it’s the same bond)

Psychology research is clear: humans are flawed decision-makers.

But even if we identify poor investor behavior, that doesn’t necessarily mean a market opportunity exists that we can exploit. As discussed, other smart investors will surely be privy to the situation and they will immediately exploit the opportunity, putting pressure on our ability to profitably take advantage of market participants. We want to avoid competition, but to avoid competition, we need to understand the competition.

Understanding the Best Poker Players

In the context of financial markets, the best pokers players are often those investors managing the largest amounts of money. They are the hedge funds with all-star managers or institutional titans running massive fund complexes. The resources available to these investors are incredible and vast. One can rarely overpower this sort of opponent. Thankfully, overpowering isn’t the only way to slay Goliath. One can out maneuver these titans because many top players are hamstrung by economic incentives.

Before we dive into the incentives of these pokers players, let’s quickly review the concept of arbitrage. The textbook definition of “arbitrage” involves a costless investment that generates riskless profits, by taking advantage of mispricings across different instruments representing the same security. In practice, arbitrage entails costs as well as the assumption of risk, and for these reasons there are limits to the effectiveness of arbitrage. There is ample evidence for such limits to arbitrage. Examples include the following:

Fundamental Risk. Arbitragers may identify a mispricing of a security that does not have a perfect substitute that enables riskless arbitrage. If a piece of bad news affects the substitute security involved in hedging, the arbitrager may be subject to unanticipated losses. An example would be Ford and GM — similar stocks but they are not the same company.

Noise Trader Risk. Noise traders limit arbitrage. Once a position is taken, noise traders may drive prices farther from fundamental value, and the arbitrageur may be forced to invest additional capital, which may not be available, forcing an early liquidation of the position.

Implementation Costs. Short selling is often used in the arbitrage process, although it can be expensive due to the “short rebate,” which represents the costs to borrow the stock to be sold short. In some cases, such borrowing costs may exceed potential profits. If short rebate’s fees are 10% or 20%, then arbitrage profits must exceed these costs to achieve profitability. That’s a tall order.

The three frictions mentioned are important, but the biggest, most underestimated, issue for many smart poker players are the incentives of their clients:

Performance Requirements/Agency Costs. The biggest short-circuit to the arbitrage process is limits imposed by performance expectations. Consider the pressures produced by “tracking error,” or the tendency of returns to deviate from a benchmark.

Say you have a job investing the pensions of 100,000 firemen. You have a choice of investment strategies. You can invest in:

Strategy A: A strategy that you know (by some magical means) will beat the market by 1% per year over 25 years. You also know that you will never underperform the index by more than 1% in a given year; or

Strategy B: An arbitrage strategy that you know (again by some magical means) will outperform the market, on average, by 5% per year over the next 25 years. The catch is that you also know that you will have a 5-year period where you underperform by 5% per year.

Which strategy do you choose? If you are a professional money manager, the choice is often obvious, despite being sub-optimal for their investors: choose A and avoid getting fired.

Why choose A? It a bad long-term strategy relative to B!

The incentives of an investment manager are complex. Fund managers are not the owners of the capital, but work on behalf of someone who owns the capital. Financial mercenaries, if you will. These managers sometimes make decisions that ensure they maintain a job, but not necessarily maximize risk-adjusted returns for their investors. For these managers, relative performance is everything and tracking error is dangerous. In the example above, the tracking error on strategy B is just too painful to digest. Those firemen are going to start screaming bloody murder during the 5 years of underperformance, and the manager won’t be around long enough to see the rebound when it occurs after year 5. But if the manager follows strategy A, he can avoid career risk and the fireman’s pension will not endure the stress of a prolonged downturn.

Over long time frames, this arbitrage opportunity is a mile wide–you could drive a proverbial truck through it. But this agency problem–the fact that the owners of the capital can, in lean times, begin to doubt the abilities of the arbitrageur and pull their capital–precludes smart managers from taking advantage of it!

The threat of short-term tracking-error is very real. The following quotes are from a WSJ article written on Ken Heepner’s CGM Focus Fund.

First, the WSJ facts on Ken’s fund performance:

“Ken Heebner’s $3.7 billion CGM Focus Fund, rose more than 18% annually and outpaced its closest rival by more than three percentage points.”

Next, the WSJ facts on the performance of investors in Ken’s fund:

“Too bad investors weren’t around to enjoy much of those gains. The typical CGM Focus shareholder lost 11% annually in the 10 years ending Nov. 30, according to investment research firm Morningstar Inc.”

Ken’s fund compounded at 18% a year, and yet, the investors in the fund lost 11% a year, a reflection of the typical investor’s inability to time in and out of Ken’s fund. When Ken’s fund was underperforming (and the opportunity was high), they pulled capital; when his fund was outperforming (and opportunity was low), they invested more capital. On net, Ken looks like a genius, but few investors actually gained from Ken’s ability–a lose-lose proposition.

Ken’s Heebner’s experience highlights this conflict of interest problem for asset managers. The dynamics of this problem are explored in a ground-breaking 1997 Journal of Finance paper by Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, appropriately called, “The Limits of Arbitrage.” The takeaway from Ken Heebner’s experience and Shleifer and Vishny’s insights is as follows:

Smart money managers avoid long-term market opportunities if their investors are focused on the short-term.

And can you blame them? If an asset manager is compared to a benchmark every month, year, or even five years, then the client clearly cares more about short-term performance as opposed to long-term returns. Whether the asset manager is proactively protecting his / her job, or the client is actively driving the conversation around near-sighted metrics, the end result is the same.

Keys to Long-Term Active Management Success

We’ve outlined a few elements of the marketplace. First, some investors are probably making poor investment decisions, and second, some managers are unable to exploit genuine market opportunities. We encapsulate these elements in a simple equation for sustainable long-term performance in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The Long-Term Performance Equation

The long-term performance equation has 2 core elements. First, sustainable alpha. By sustainable alpha, we mean a process that systematically exploits mispricings caused by behavioral bias in the marketplace (i.e., find the worst poker players). Next, sustainable clients. Sustainable clients are important, because many of the best poker players in the game (think large asset managers with a majority of the capital), are unable to pursue long-term opportunities because their client base is too focused on the short-term (i.e., find the best poker players and understand their actions).

Based on the equation, if one could identify a processes with an edge (i.e., sustainable alpha) that require long-term discipline to exploit (i.e., sustainable clients), it is likely that this process will serve as a promising long-term strategy.

Moving from Theory to Practice

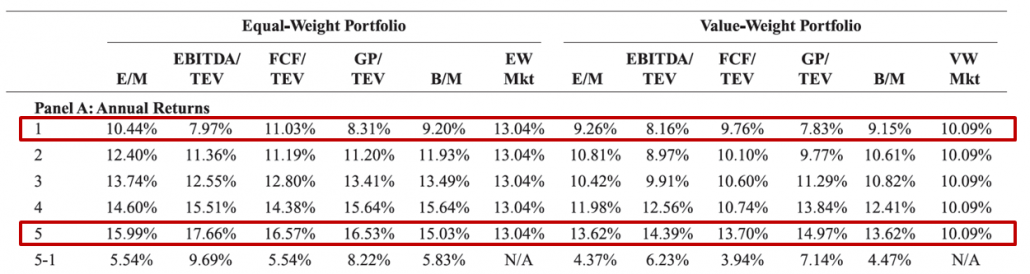

Much of the discussion above outlines an intellectual framework for successful active investing. The building blocks to create sustainable performance, framed appropriately, are simple to follow. To put a little bit of meat on the bone, we provide an example of how this construct works in practice. Our example is value investing, the practice of purchasing portfolios of firms with low prices to some fundamental price metric (e.g., P/E, P/B, or EBITDA/TEV). Figure 6 below is taken from our paper, “Analyzing Valuation Measures: A Performance Horse Race over the Past 40 Years,” published in the Journal of Portfolio Management. In the paper, we run a horse race among valuation metrics and tally the results. Row “1” is the performance of the top 20% most expensive stocks and row “5” is the performance of the 20% cheapest stocks, annually rebalanced.

Figure 6: Value Investing Results

What do you notice? Across the board, the historical evidence is clear: cheap stocks have outperformed expensive stocks–by a wide margin. The equally-weighted portfolio of cheap stocks measured by EBITDA/TEV earns a 17.66% compounded annual return, whereas, the most expensive stock portoflio earns 7.97%–nearly a 10% spread in performance. A spread of ~10% per year, compounded over a long time period, would lead to huge differences in the value of a portfolio. One can argue over reasons why the spread is large–risk or mispricing–but nobody can dispute the empirical fact: Cheap stocks have outperformed expensive stocks.

Now we Have the Facts. Next Step, Identify the Bad Poker Players at the Value Investing Table

Let us first identify those market participants that are making poor decisions.

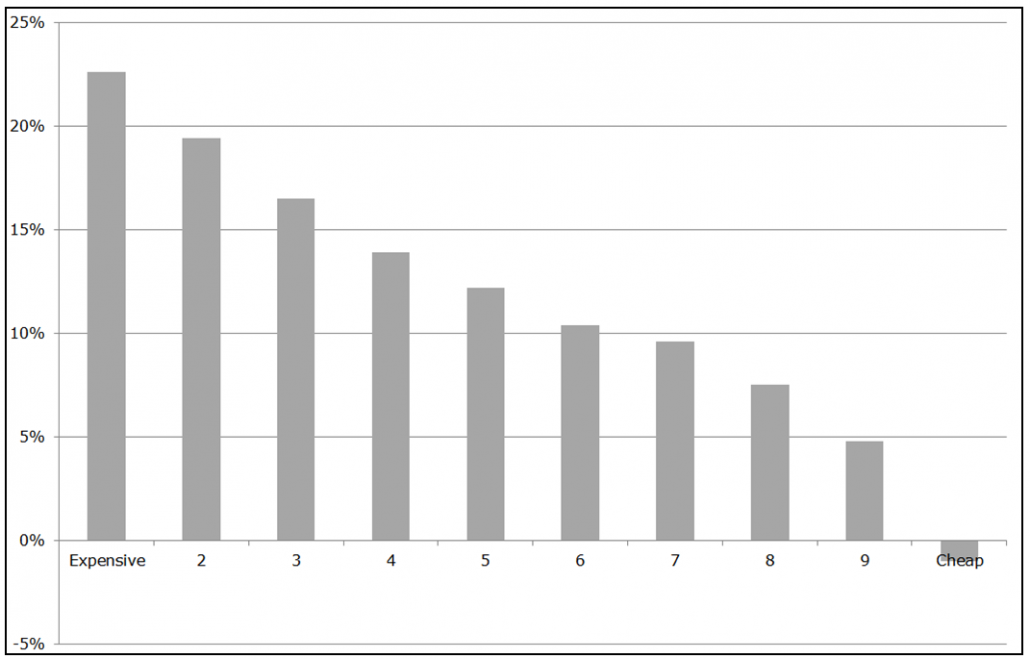

The poor poker players at the value investing table were first discussed by Lakonishok, Shleifer and Vishny (LSV) in their paper, “Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation, and Risk.” The poor behavior they investigate is referred to as representative bias, a situation where investors naively extrapolate past growth rates too far into the future. Figure 7 below highlights the concept from the LSV paper using updated data from Dechow and Sloan’s 1997 paper, “Returns to Contrarian Investment Strategies: Tests of Naive Expectations Hypothesis.” The horizontal axis represents cheapness and sorts securities into buckets based on expensive stocks (low book-to-market ratios) and cheap stocks (high book-to-market ratios). The vertical axis represents past 5 year earnings growth rates for the respective valuation buckets. Stocks in Bucket 10 are the cheapest, and they exhibited (on average) ~ a negative 1% earnings growth over the past five years.

The relationship is almost perfectly linear. Cheap stocks have terrible past earnings growth, whereas expensive stocks have had wonderful earnings growth over the past 5 years. No real surprise there, but interesting to see how the data fits so well to this relationship.

Figure 7: Investors Extrapolate Past Growth Rates into the Future

Figure 7 underscores the general market expectation that past earnings growth rates will continue into the future. Expensive firms are expensive because market participants believe past growth rates will continue. Meanwhile, cheap stocks are cheap for a reason–the market believes their poor past growth rates will continue as well.

But does this really happen? Do cheap stocks have poor future growth and do expensive stocks have strong future growth? We can test whether or not this market assumption occurs, on average, OR if there is a systematic flaw in market expectations.

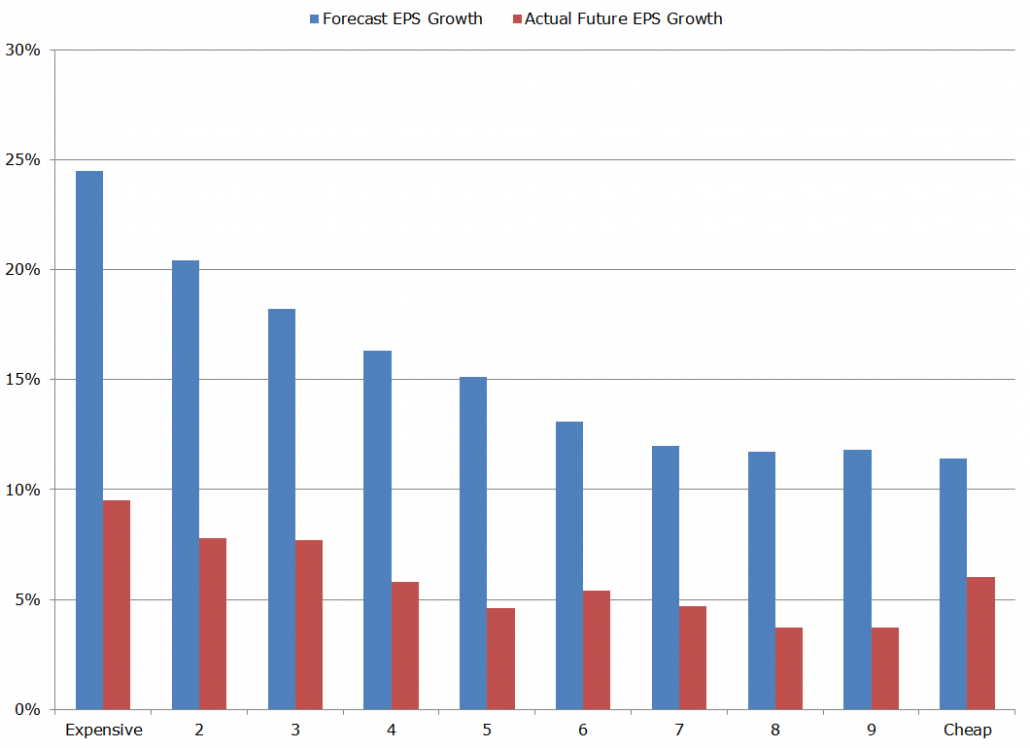

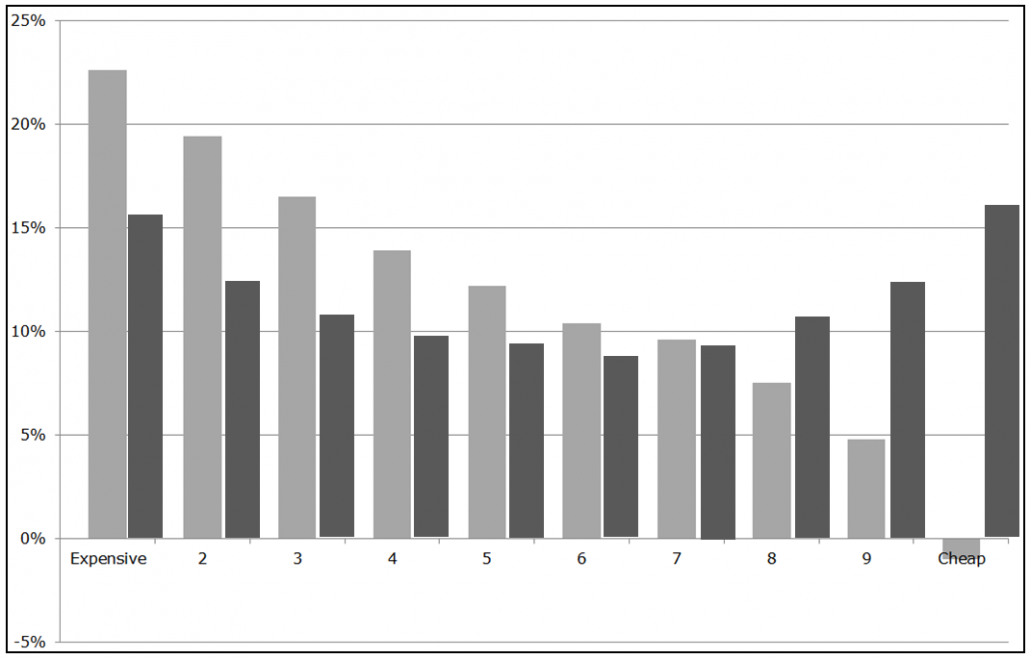

In Figure 8, we look at what happens to earnings growth over the next five years. Specifically, did the cheap stocks continue to exhibit terrible earnings growth as predicted? Did expensive stocks maintain their terrific earnings growth?

The chart below is evidence of systematically poor poker playing. The realized earnings growth (dark bars) systematically reverts to the average growth rate across the universe. Cheap stocks outperform growth expectations and expensive stocks underperform growth expectations, systematically. This unexpected deviation from expectations leads to price movements that are favorable for cheap “value” stocks, and unfavorable for expensive “growth” stocks. Growth investors underperform; value investors outperform; and passive investors receive something in between.

This behavioral phenomena explains much of the spread in returns between value and growth securities. (We explore a related concept by Dechow and Sloan in the appendix).

Figure 8: Realized Growth Rates Systematically Mean-Revert

To summarize: Markets, on average, throw cheap stocks under the bus and clamor for expensive stocks. From a poker playing perspective, this is an example of a systematically poor strategy. Assuming that a great hand last round equals a winning hand in the next round is a losing approach. But that’s what people do in the financial markets! This is how the worst poker players are playing the game. But what are the best poker players doing and can they actually exploit the poor poker players?

Who are the Best Poker Players at the Value Investing Table?

It is unlikely that we will ever be the smartest investors in the world–somebody will always be smarter. But if we aren’t going to be the best poker player at the investing table, how can we win?

We can win by finding those market opportunities where the smartest investors are reluctant to participate.

But when will smart investors NOT want to participate? Using our example above, who wouldn’t want to partake in what appears to be a straightforward way to beat the market (buy cheap stocks, hold, sell once earnings growth reverts to the mean)?

As mentioned previously, really smart investors often get endowed with large amounts of capital from a large group of investors (think DFA, AQR, Blackrock, Fidelity, and so forth). This makes sense on many levels–investors want to give their money to smart people. The challenge is that the really smart investors are often managing money on behalf of investors that suffer from behavioral biases (System 1 thinkers). Shleifer and Vishny highlight, and the Ken Heebner example confirms that many smart market participants are hamstrung by the short-term performance measures imposed upon them by their investors. “How did you perform against the benchmark this quarter? What do your results look like year to date? What new trends are you exploiting this month?” All of these questions are commonplace in the market. The threat of being fired and replaced with a passive portfolio of Vanguard funds is always close in the rearview mirror. And when job security / client expectations trump long-term value creation, funny things happen.

So what is the difference between short-term (incorrect) and long-term (correct) horizons? How patient do our good poker players have to be in order to realize their edge?

Let’s consider an example from 1994 to 1999. Barron’s famously stated the following regarding Warren Buffett’s relative performance:

“Warren Buffett may be losing his magic touch.”

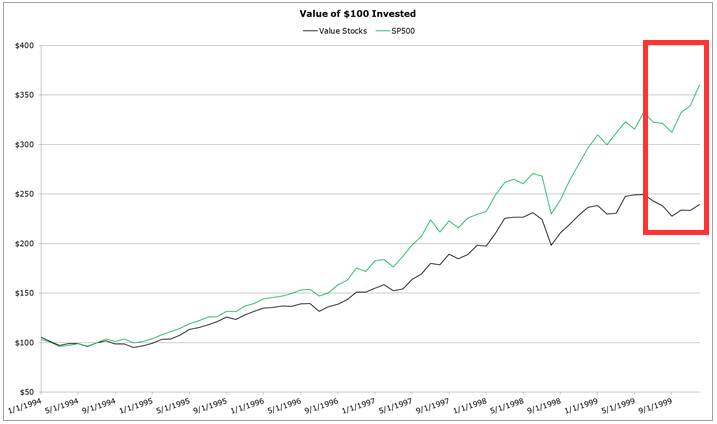

Barron’s observation, in many respects, was fully warranted. Value investors as a group were destroyed by the market in the late 1990’s. Generic value investing (shown in Figure 9 below) underperformed the broader market by a large margin for 6 long years!

Figure 9: Value Investing Can Underperform

Clearly, being a value investor requires patience and faith that few investors possess. In theory, value investing is easy–buy and hold cheap stocks for the long haul–in practice, true value investing IS ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE.

Using Ken French’s data, we examined just how painful it was to be a value investor in the late ’90s.

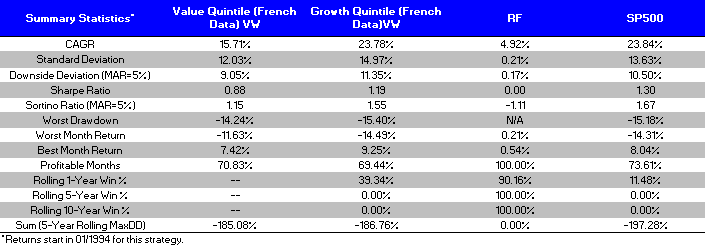

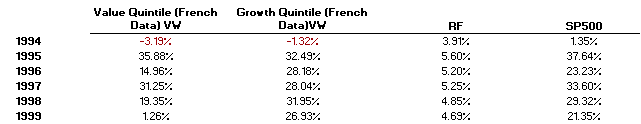

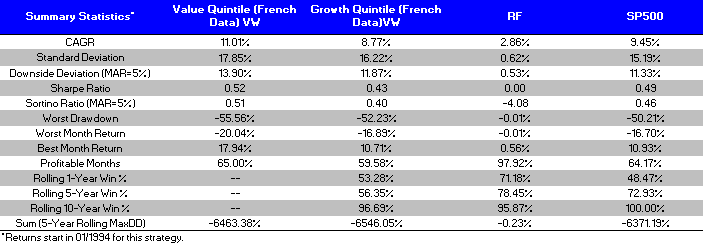

We examine the returns from 1/1/1994-12/31/1999 for a Value portfolio (High B/M quintile, VW returns), Growth portfolio (Low B/M quintile, VW returns), Risk-Free return (90-day T-Bills), and SP500 total return. Results are shown in Figure 10 below. All returns are total returns and include the reinvestment of distributions (e.g., dividends). Results are gross of fees.

Figure 10: Summary Statistics (1994-1999)

Talk about a beat-down! Looking at the annual returns (shown in Figure 11), value investing lost every year to a simple market allocation!

Figure 11: Annual Returns

A plain vanilla index fund outperforms value six years in a row, sometimes by double digit figures! To simulate what these value managers went through, ask yourself this question:

If your asset manager underperformed a benchmark for six years, at times by double digits, would you fire them?

For 99.9% of investors, that answer would be a resounding YES (and giving someone a six year trial period is probably out of the question as well). Most–if not all–professional asset managers would be fired given this underperformance. Truly active value investing is practically impossible to follow for many pros.

After viewing the 6-year underperfomance of value, we need to highlight 2 conclusions:

- For a long-term investor, a 6-year stretch of pain is a truly great thing. Why? Because the competition from the best pokers players is going to be limited, careers and tracking error trump performance!

- Sustainable active investing requires special clients. Disciplined investors with long term horizons that are indifferent to short-term relative performance ar eessential. These unique clients are what we label “Sustainable Clients” in Figure 5.

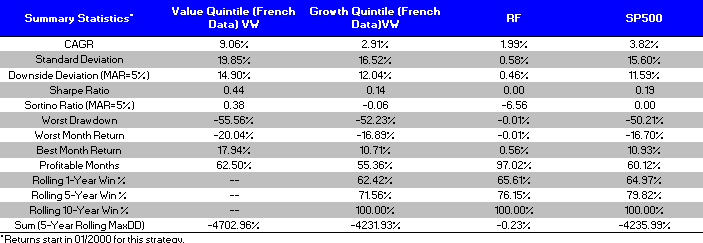

Now, suspend reality for a moment and let’s imagine that an active value manager had clients that didn’t flee for the exits in 1999. What would their hypothetical returns look like in the long run? As you can see below in Figure 12, value quickly recovers and outperforms the entire time period thereafter. Here are the returns to the same portfolios from 1/1/2000 – 12/31/2013, the 14 years following the 6-year underperformance:

Figure 12: Summary Statistics (2000-2013)

Sticking with the value strategy, although painful, was richly rewarded with a 5%+ edge–per year–over the market benchmark from 2000-2013.

Over the entire cycle, patient, disciplined investors were also rewarded. Here are the results (Figure 13) over the entire time period, measured from 1/1/1994 to 12/31/2013:

Figure 13: Summary Statistics (1994-2013)

Bottom line: For a long-term investor, value investing was the optimal decision, but for many of the smartest asset managers in the world, value investing was simply not feasible as a business.

Putting it all together

We’ve used value investing as a laboratory to highlight how the sustainable active investing framework can identify long-term winning strategies. Value investing is not the only active strategy that fits nicely in this paradigm. There are other investing approaches that follow similar fact patterns, such as concentrated momentum, and concentrated low-volatility strategies. The lesson from all of these approaches is that successful active investing is simple, but not easy. If active investing were easy, everyone would do it, and if it were too complex, it probably wouldn’t work.

In summary, our long-term performance equation highlights 2 required elements:

- A sustainable process that exploits systematic investor expectation errors.

- A sustainable clientele that has a true long-term horizon.

These 2 pieces of the puzzle map back to the classic lessons of poker:

- Identify the worst poker player at the table.

- Identify the best poker player at the table.

And these classic lessons map into the 2 pillars of behavioral finance:

- Understanding behavioral bias and how investors form expectations.

- Understanding market frictions and how they affect market participants.

So the next time you hear some market commentator suggest that successful active investing is impossible, simply nod in agreement, and walk away. The less competition, the better.

Appendix

Value Investors Club Background

Valueinvestorsclub.com (VIC) is an “exclusive online investment club in which top investors share their best ideas.” Many business publications have heralded the site as a top-quality resource for those who can attain membership (e.g., Financial Times, Barron’s, BusinessWeek, and Forbes). Joel Greenblatt and John Petry, managers of a large hedge fund, Gotham Capital, founded the site in 2000 with $400,000 of start-up capital. Their goal was for VIC to be a place for the highest-quality ideas on the Web. The investment ideas submitted on the club’s site are broad but are best described as fundamentals-based. VIC states that it is open to any well thought out investment recommendation, but that it has particular focus on long or short equity or bond-based recommendations, traditional asset undervaluation situations, such as high book-to-market, low price-to-earnings, liquidations, etc., and investment ideas based on the notion of value as articulated by Warren Buffett (firms selling at a discount to their intrinsic value irrespective of common valuation ratios).

VIC managers try to ensure that only members with significant “investment ability” are admitted to the club. Accordingly, membership in the club is capped at 250 and the approximate acceptance rate is 6% (Per email correspondence with VIC management). As a result of the low acceptance rate, membership started at 90 members in 2000 and did not reach the 250 cap until 2007. Admittance is based solely on a detailed write-up of an investment idea (typically 1000 to 2000 words). Employer background and prior portfolio returns are not part of the application process. If the quality of the independent research is satisfactory and the aspiring member deemed a credible contributor to the club, he is admitted. Once admitted, members are required to submit at least two “high-quality” investment ideas per year to continue as members and receive unrestricted access to the ideas and comments posted by the VIC community.

Statistics Definitions

- CAGR: Compound annual growth rate

- Standard Deviation: Sample standard deviation

- Downside Deviation: Sample standard deviation, but only monthly observations below 41.67bps (5%/12) are included in the calculation

- Sharpe Ratio (annualized): Average monthly return minus treasury bills divided by standard deviation

- Sortino Ratio (annualized): Average monthly return minus treasury bills divided by downside deviation

- Worst Drawdown: Worst peak to trough performance (measured based on monthly returns)

Naive Forecasts or Naive Reliance of Bad Forecasts?

Dechow and Sloan 1997 argue that the value anomaly is not driven by naive extrapolation by irrational investors as LSV 1994 suggested, but rather, the outperformance of value stocks is driven by market participants’s flawed faith in analysts forecasts, which are systematically overoptimistic. In Appendix Figure below, Dechow and Sloan look at the relationship between the earnings growth forecasted by sell-side analysts and the actual earnings growth (note, the sample used below is different than the sample above due to I/B/E/S data constraints). The chart below first splits firms into 10 buckets based on their price. The left bucket contains the most expensive firms, while the far right bucket contains the cheapest firms. The black bars represent past earning growth rates, while the blue bars represent future earning growth rates.

What do we see? A few things:

- Systematic sell-side overoptimism (blue bars are always higher than the red bars)

- Mean-reversion in fundamentals, unappreciated by sell-side analysts (red bars are roughly equal across buckets)

Appendix Figure: Value Investing Results

If investors anchor on sell-side expectations about the future, investors will be most surprised when the realized growth on expensive stocks underwhelms forecasts, and investors will be least surprised when the realized growth rates on cheap stocks underwhelm forecasts.

Copyright © Wesley Gray, AlphaArchitect