by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

Four questions I’m pondering at the moment:

Is “low rates and low inflation forever” the new consensus? Economists and pundits have been predicting a rise in interest rates for a number of years now, but the professional investors I talk to these days almost all seem convinced that rates will stay “lower for longer.” Many of the investors, portfolio managers and analysts I meet with are probably macro tourists so this is anecdotal, but I get the sense that low interest rates and low inflation for the foreseeable future is now the consensus among these professional investors. It’s amazing to me how quickly opinions have shifted from the 2009-2013 thinking of “interest rates and inflation are going to scream higher because of the Fed” to the 2014-2015 mindset of “we think interest rates and inflation will be subdued for the next decade or so.” The secular stagnation thesis is gaining support.

Is it possible that both of these consensus lines of thinking will be proven wrong?

Will the financial advisor ranks be cut in half within the next 10 years? Uber-financial advisor Ric Edelman is on record saying he thinks advances in technology could mean as many as half of all existing financial advisors could be out of a job by the next decade. There are 10,000 baby boomers retiring every day for the next 20 years, so obviously many advisors will be retiring as well, considering the average age of all financial advisors in somewhere in the 50s. But the fact that there are 10,000 baby boomers retiring a day means that the demand for new advice is going to be enormous. Some numbers from a recent report by US Trust:

There are now nearly 1.8 million households in the U.S. with $3 million or more, including 950,000 households with $3 million to $5 million, 600,000 households with $5 million to $10 million, and 250,000 households with more than $10 million in assets.

There’s a huge difference between accumulating wealth and preserving or spending down said wealth. These people are going to require advice regarding taxes, portfolio withdrawal strategies, estate and trust issues and social security payouts in addition to investment management in a fairly tricky market environment with extremely low interest rates. We could see some consolidation among existing advisory practices, but I think the demand for financial advisors will bring in a wave of new entrants to manage the money for retiring boomers and their heirs.

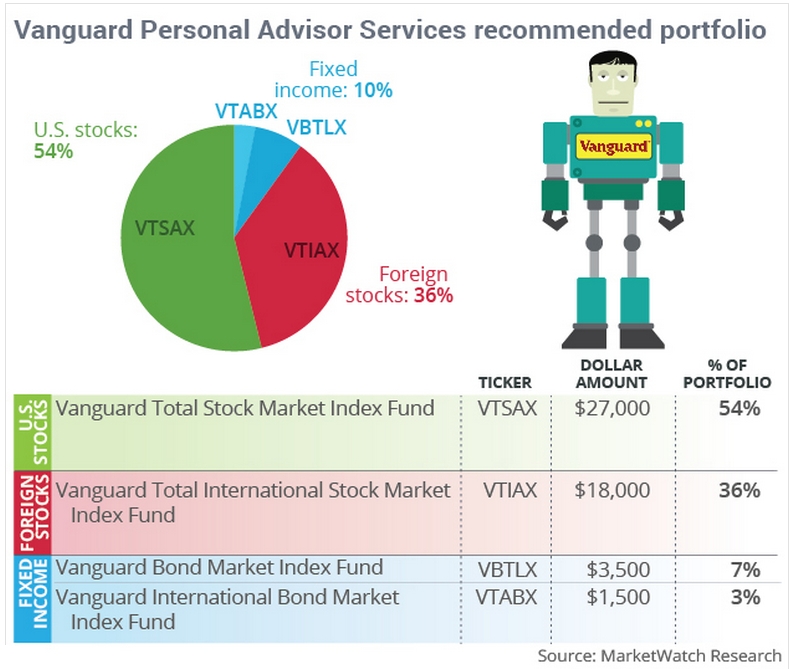

Are robo-advisors really that innovative? Vanguard has quickly added in the neighborhood of $20 billion to their hybrid robo-advisor service that gives their clients the opportunity to talk to a financial advisor when they have planning questions in addition to an asset allocation service. Victor Reklaitis at MarketWatch tried out the new robo offering himself and discovered that the recommended portfolio he got is basically the same thing as Vanguard’s 2040 Targetdate Retirement Fund. As you can see here, the fund is fairly simple:

There’s nothing wrong with a simple portfolio. I’d argue many individual investors could do much worse for themselves than this simple offering. But this goes to show you that robo-advisors aren’t doing anything groundbreaking. They’re simply building low cost portfolios for people and handling the rebalancing for them. Investors could easily do this on their own if they wanted to.

What this suggests to me is that what people truly desire is some attention from an outside party. They want someone else to do these things for them or offer guidance with their decisions. In some ways it relieves people from the burden of making the decisions on their own. As long as it works, I think it’s a great service. But it’s really just a different packaging of existing products and services in a more efficient manner. This efficiency is something more financial firms should be paying attention to.

Does 2004-2007 really count as a rising rate environment? The Fed raised short-term rates from 1% in early 2004 in a stair-step approach over time all the way up to 5.25% by the summer of 2007. So technically this was a rising interest rate environment, but it’s unlike any we’ve ever seen because credit was so easily available to pretty much anyone that wanted it. By now everyone has heard about the strawberry farmer in California who received a $720,000 mortgage even though he made just $14,000/year. Credit wasn’t exactly tightening throughout this rising rate cycle.

It may be somewhat useful to make comparisons to that period of time to see how certain interest rate sensitive asset classes such as junk bonds, REITs, dividend-paying stocks or bonds performed, but my guess is that particular environment doesn’t do a great job of showing investors what a typical rising rate scenario would look like (assuming there is such a thing).

Further Reading:

Portfolio Management & Decision Fatigue

What Do Low Interest Rates Mean for Stock Market Returns?

Subscribe to receive email updates and my quarterly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs