by Cam Hui, Humble Student of the Markets

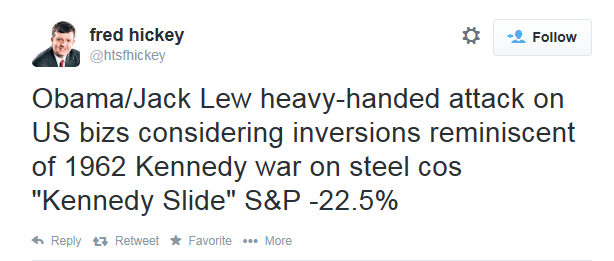

In light of the recent Obama Administration's new rules intended to curb tax inversions, there have been a lot of controversy over corporate tax policy. Fred Hickey went so far as to warn of a Kennedy-esque bear market:

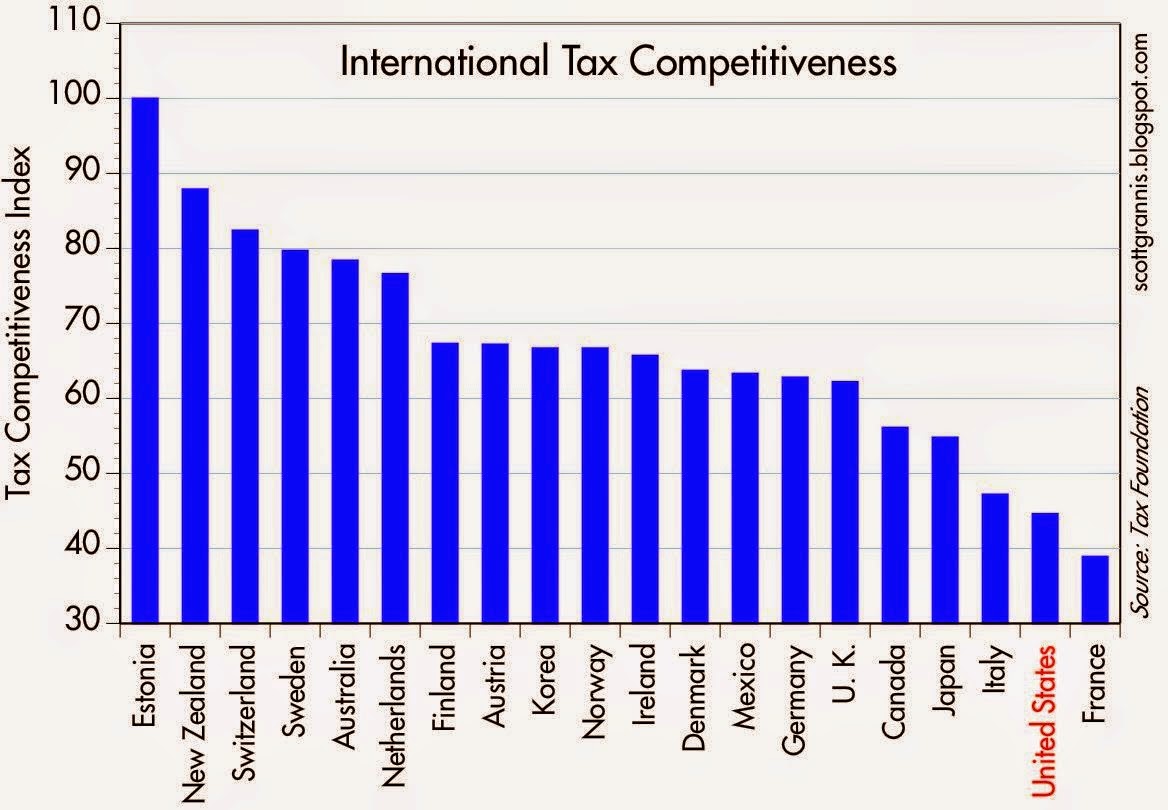

Scott Grannis has railed against US tax policy for years. US tax competitiveness stinks, he railed:

Today the Tax Foundation released its 2014 index of International Tax Competitiveness. Of the 34 countries ranked on the basis of "more than forty variables across five categories: Corporate Taxes, Consumption Taxes, Property Taxes, Individual Taxes, and International Tax Rules," the U.S. came in #32, only a few points ahead of notoriously tax-loving France.

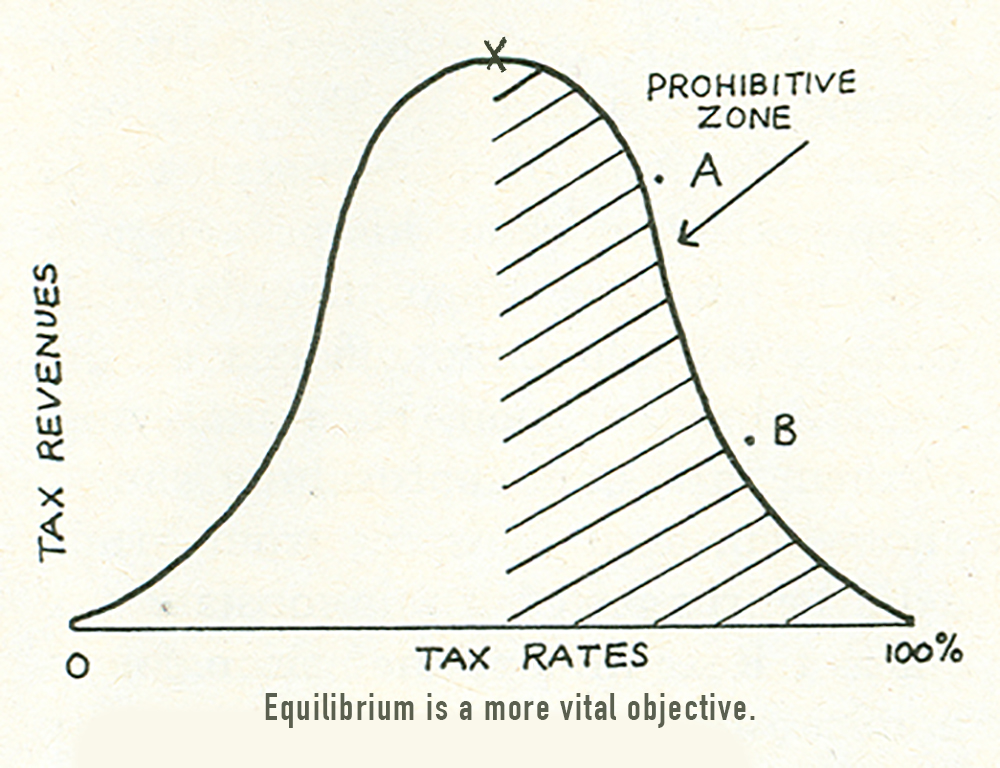

Grannis has long been an advocate of slashing US corporate tax rates:

At 35%, the U.S. corporate income tax rate is the highest of any developed country. The fact that corporations are refusing to repatriate trillions of dollars of overseas profits is proof that it is negatively impacting the economy. Overseas profits have already passed through the tax tollgate once, but to subject them to another 35% just for bringing them back to the states is unconscionable to any responsible corporate executive.

In an ideal world, corporate profits should not be taxed at all, since the burden of corporate taxes falls almost entirely on the customers and employees of corporations. In the end, only people pay taxes, and it's highly inefficient to tax businesses and individuals separately. Today, capital faces double and triple taxation: first on business profits, again when shareholders pay tax on dividends (paid out of after-tax profits) received, and again if and when capital gains are realized. Punitive tax burdens inhibit risk-taking and capital formation, and that in turn leads to slow growth.

Changing the ecosystem

As for my views, the question of correct tax policy is way beyond my pay grade. What I do know is that when tax policy changes, it affects the economic ecosystem in subtle ways that investors might not expect.

Instead of focusing on what should be, investors should focus on what is and how it is changing. For another perspective, consider the views of John Hussman (whom I respect, but do not necessarily endorse):

The central point is this. The U.S. economy has shifted course from one of productive capital accumulation to a reliance on continuous expansion of debt in excess of the economic ability to repay it. Call this the Ponzi Economy.

The U.S. Ponzi Economy is one where domestic workers are underemployed and consume beyond their means; household and government debt make up the shortfall; corporate profits expand to a record share of GDP as revenues are sustained by household and government deficits; local employment is replaced by outsourced goods and labor; companies refrain from productive investment, accumulate the debt of other companies and issue new debt of their own, primarily to repurchase their own shares at escalating valuations; our trading partners (particularly China and Japan) become our largest creditors and accumulate trillions of dollars of claims that can effectively be traded for U.S. property and future output; Fed policy encourages the yield-seeking diversion of scarce savings toward speculation in risky securities; and as with every Ponzi scheme, everyone is happy as long as nobody seeks to be repaid.

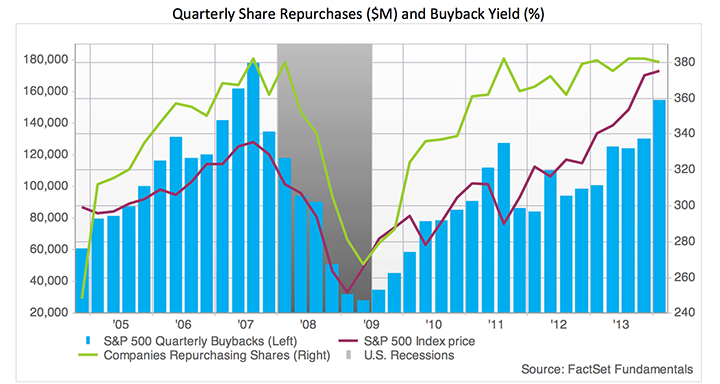

Hussman believes that investors should care because corporate executives are focusing too much on share buybacks. In fact, they are issuing debt (and junk debt if the balance sheet is shaky) in order to boost EPS by decreasing the number of shares outstanding and "issuing corporate debt to repurchase equity presently represents value destruction":

We view corporate and junk yields as insufficient to justify their additional credit risk at present levels, and we are particularly concerned at the increasing issuance of corporate debt to obtain what amounts to leveraged exposure to equities at historically extreme valuations (either through share buybacks or acquisitions). Buybacks are not a return of capital to shareholders – they are partly a leveraged speculation on shareholder’s behalf, partly a strategy to enhance per-share earnings by reducing share count, and partly a way to reduce the dilution from stock-based compensation to corporate insiders. Moreover, repurchases move in tandem with corporate debt issuance, which is another way of saying that the history of stock buybacks is one of companies using debt to buy their stock at overvalued prices.

Keep in mind also that corporate share repurchases have no tendency to concentrate at points of depressed valuation, and but have instead been disproportionately aggressive at points that have historically represented severe overvaluation. The chart below (h/t Thad Beversdorf) illustrates this regularity. See The Two Pillars of Full-Cycle Investing for additional data.

Why does any of this matter? Whether Hussman's comments are on target or not, it does show that companies are buying back a lot of their own shares. In some cases, they are borrowing, or levering up the balance sheet to do so. Under the current tax regime, some CFOs may feel that they can lower their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) by shifting financing from equity to debt. In effect, CFOs are effecting a slow-motion LBO of their own companies.

Hussman's comments are correct if companies are already at their optimal capital structure, but the perverse effects of option-related compensation incentives are pushing managements to overly stretch their balance sheet with debt. They are incorrect if these companies have excess equity and they are merely lowering their WACC by shifting their capital structure.

The perverse effects of lower corporate taxes

With that preamble, now imagine that the GOP won a landslide victory in the Senate in November and they controlled the House. What would happen if the Republican dominated Congress were to lower the corporate tax rate?

The economic ecosystem would shift and, in aggregate, CFOs would find the cost of equity cheaper compared to debt. They would therefore delever the balance sheet by replacing equity with debt. We would see more equity financing (and therefore more supply) while debt would get retired (especially if the Fed starts to raise rates).

The net effect of such a shift could see a flood of equity financing that was beyond the capability of the market to absorb, and in light of a tightening Fed, spark an equity bear market.

To be sure, there would be a bullish equity effect as lower tax rate as the market bids up equity prices. However, the effective corporate tax rate can be very low, though the notional rate is still relatively high, because multi-nationals have learned to lower their taxes by keeping cash in offshore subsidiaries. How whether the bullish re-rating effect overwhelms the bearish higher equity supply effect, or vice versa, I have no idea.

The point of this post is that there are no easy answers in economics and tax policy. If you down on widget A, unpredictable effects occur and widgets G and K move up unexpectedly.

Before you start writing nasty notes and emails to me, note that I wrote that lower corporate tax rates could lead to a bear market, not would. There are never any certainties in forecasting. However, investors should pay attention to possible perverse effects of a change in the economic ecosystem.

Copyright © Humble Student of the Markets