by Lance Roberts of STA Wealth Management,

In this past weekend's newsletter (subscribe free for weekly technical and allocation updates) I discussed an issue that has concerned me for some time. It is an issue that was prevalent in the late 90's as markets surged to new heights. It was an issue that resurfaced again in 2007 as readily available liquidity and leverage made the financial markets the "only game in town." Right now, we see the resurgence of the same notions once again which is simply: "Fundamentals don't matter."

In this past weekend's missive, I noted an article from the Wall Street Journal discussing the closure of another hedge fund. The closure of a hedge fund is not unusual, it was the stated reason of the closure that was most striking. To wit:

"In a May regulatory filing, the firm wrote it believed that "making investment decisions by looking solely at the fundamentals of individual companies is no longer a viable investment philosophy."

Do not misunderstand me. Fundamentals DO matter very much over the "long term." There is ample evidence that future returns are very much linked to valuation at the time of the initial investment. Forbes recently penned an article on this very issue.

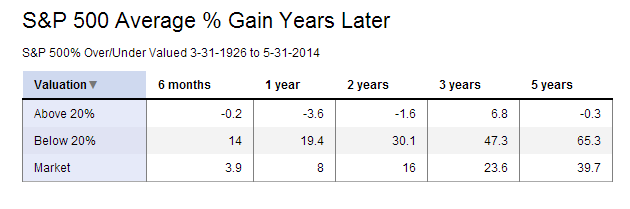

"Looking at history, the stock market's returns depend a lot on where equity valuations are when you start the clock.Ned Davis Research has done the math, comparing the actual levels of the S&P 500 Index each month with a 'normal' valuation of the index based on fundamental factors like P/E, dividends, earnings, and cash flows. They identified points when the market was over- or undervalued by at least 20% and they crunched the numbers on performance after each of these points."

"The performance difference is dramatic. On average, one year after a low valuation, the market rose by 19.4%. One year after a high valuation, it dropped by 3.6%. When the market has been fairly valued, it increased 8.0%. Also note the returns one, two, three and five years later. Data through 5-31-2014 shows the market to be 33.240% overvalued."

[Note: Yes, I know, the majority of the "mainstream" analysis focuses on "forward operating earnings" which currently suggests that the markets are fairly valued. However, historical valuation measures are based on "reported trailing earnings," which are "in your pocket earnings," versus "operating earnings" which are essentially "what earnings would have been if reality hadn't happened." Furthermore, analysts are historically about 30% overly optimistic in their estimates, so caution is advised.]

Duration Mismatch

There is also just a good bit of "common sense" involved in this analysis. What is particularly interesting is the "behavioral" aspect of individuals when it comes to investing. Individuals will scour the internet to find the best deal on everything from a pair of shoes to a television. It is a source of "bragging" rights to tell their friends how cheaply they obtained their prize possession. However, when it comes to investing, they disregard "value" altogether believing that something that has gone up 100% is a better buy than something that has declined 20%.

What is truly ironic is that when it comes to buying "crap" we don't really need, people will spend hours researching brands, specifications and pricing. However, when it comes to investing our "hard earned savings," we tend to spend less time researching the underlying investment and more time fantasizing about our future wealth.

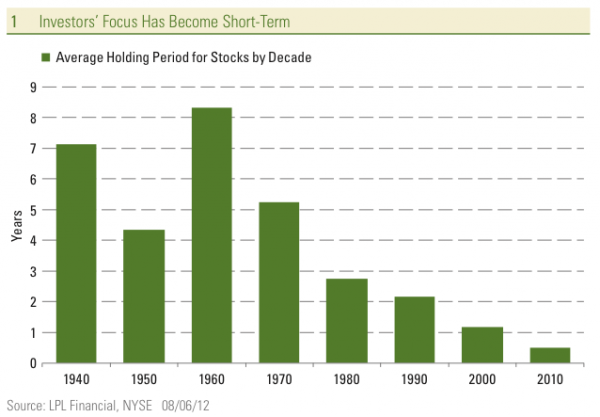

This "mentality" leads to what I call a "duration mismatch" in investing. While valuations give us a fairly good assessment about future returns, such analysis is based on time frames of five years or longer. However, for individuals, average holding periods for investments has fallen from eight years in the 1960's to just six months currently.

The point to be made here is simple. The time frame required for fundamental valuation measures to be effective in portfolio management are nullified by short-term investment horizons.

This "duration mismatch" is why I maintain a focus on price momentum and trend analysis. Over shorter duration periods, one month to one year, it is price movement that tells the underlying story. Price is a reflection of current "investor psychology" which can, and often does, detach from the underlying fundamentals.

It is this "detachment" that causes speculative manias in the financial markets whether it is "tulip bulbs" or "dot com" stocks. However, the one thing that all speculative manias have in common is a current belief that "this time is different." Unfortunately, this has never been the case.

Will Fundamentals Ever Matter?

There is growing evidence that we are rapidly entering into the final stage of the current bull market cycle. This is not a "bearish" bit of commentary; it is just "what is." I discussed this idea recently in "Could Stocks Melt Up?"

"However, looking ahead to 2015 is where things get interesting. The decennial pattern is certainly suggesting that we take advantage of any major correction in 2014 to do some buying ahead of 2015.

As shown in the chart above, there is a very high probability (83%) that the 5th year of the decade will be positive with an average historical return of 21.47%. However, 2015 will also likely mark the peak of the cyclical bull market as economic tailwinds fade, and the reality of an excessively stretched valuation and price metrics become a major issue."

With investor exuberance mounting, a high degree of complacency and relatively little volatility, all the ingredients are in place for the markets to push higher in the short term. The rising "panic" for individuals to get into the market is an "emotional bias" that has nothing to do with underlying fundamentals or valuation measures.

Will investing based on fundamentals eventually find favor once again with investors? Maybe, but I am not sure. The problem is that market participants no longer view the financial markets as a place to invest savings over the "long term" to ensure future purchasing power parity. Today, they view the markets as a place to "create" wealth to offset the lack of savings. This mentality has changed the market dynamic from investing to gambling.

The issue for portfolio managers is in trying to justify valuations to support an investment thesis. This is a particular problem for portfolio managers who potentially suffer "career risk" for not being invested in the right stocks as markets rise. Since individuals make investment decisions based on recent performance, a manager who lags his benchmark for very long is likely to be unemployed. However, this eventually creates a "valuation justification trap," that leads to rather nasty reversions when reality collides with theory. Of course, the manager is then blamed for "not having seen it coming."

This is not a new concept. It is one that has played out repeatedly in history. As legendary investor Seth Klarman of Baupost Capital recently wrote:

"A skeptic would have to be blind not to see bubbles inflating in junk bond issuance, credit quality, and yields, not to mention the nosebleed stock market valuations of fashionable companies like Netflix and Tesla. The overall picture is one of growing risk and inadequate potential return almost everywhere one looks. There is a growing gap between the financial markets and the real economy.

Not surprisingly, lessons learned in 2008 were only learned temporarily. These are the inevitable cycles of greed and fear, of peaks and troughs."

This "time IS different," but only from the standpoint that the current variables are not the same as they were previously. Unfortunately, it will be the "same as it ever was" as it is realized how "overvalued" the markets were and that only "dumb money" bought stocks there. Fundamentals will matter, but only after the fact.

Copyright © STA Wealth Management