It’s easy to beat the S&P 500. Just hold all stocks in the S&P 500 in an equal amount. This “equal weighted” index would have outperformed the cap-weighted S&P by more than 6% annually over the past five years. What’s the trick? Just ignore risk.

There’s more risk in an equal-weighted S&P 500 stock strategy. Once the extra risk is accounted for, the strategy is a zero-sum game. See No Free Lunch From Equal Weight S&P 500 for a detailed explanation.

The extra risk in equal-weighted strategies tends to get shuffled into the background in the hype surrounding this and other so-called Smart Beta Strategies. Research Affiliates (RA) recently published an article in their February newsletter, Fundamentals, that provides an example of this. Here is a quote from their article:; “[W]e find that traditional indexing—and active managers who hug the benchmark (closet indexers)—deliver below-average returns.”

Is this statement true? It depends on what’s meant by “average returns”. To find out, I went to the endnotes of the article, “By definition, broad cap-weighted indices match the return of the market portfolio; that is, the aggregate return of all the stocks held at market weights. In other words, traditional indices deliver the market-weighted average return. They do not, however, deliver the return of the average asset.”

Average return in this case means “average asset” return, which is the simple average return of each stock individually without consideration to the size of each company. It’s a fancy way of saying equal-weighted index. What this definition doesn’t mean is the average investor return or the average actively managed return. Those returns are much lower.

There are problems with using the average asset return as a benchmark for performance. First, there isn’t enough supply of stock available for everyone to equal weight the markets. Second, those who do equal weight accept more risk than those who cap-weight the same stocks.

Let’s assume an index holds two stocks. One is a rock solid $500 billion conglomerate and the other is a $5 million penny stock issued by Rick’s Waffle Shop. In 2013, the conglomerate earned a total return of 4% and Rick’s Waffle Shop had a total return of 100% (I make great waffles). In line with the RA article, the “average asset” has outperformed the cap-weighted index by a whopping margin. The equal weight index return was 52% while the cap-weighted return was only 4% plus a bit more.

A 52% return is more attractive than a 4% return, but is it fair to tell all investors that there’s a free lunch waiting to be served at the Equal Weight Café? I don’t think so.

Let’s assume there are only 1,000 investors in the world with $500 billion in total to invest and that they’ve all bought into equal weighting. A two stock index would require half of the money be invested in the conglomerate and the other half in Rick’s Waffle Shop.

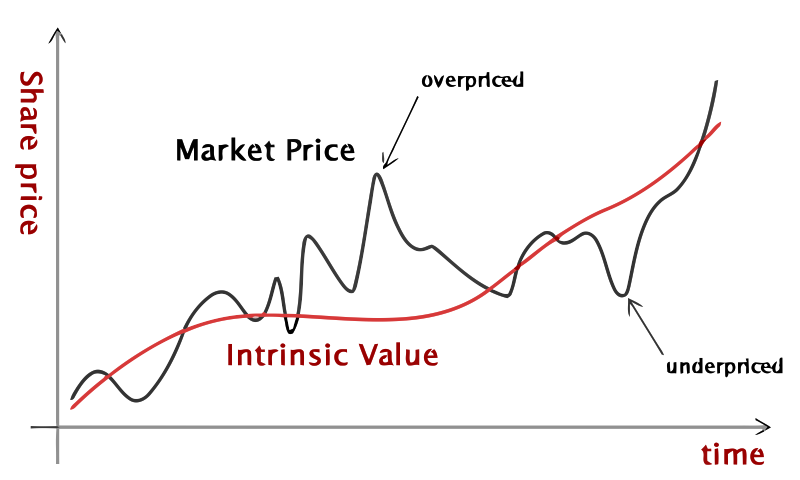

The only way for all 1,000 investors to equal weight in both companies is if both companies had the same market capitalization. Both the giant conglomerate and Rick’s Waffle Shop would have to be worth $250 billion. Thus, in theory, equal weighting drives up the price of small stocks and adds risk while driving down the price of large stocks and reduces risk. I’d like that as the purveyor of delicious waffles, but the conglomerate would hate it.

It is widely known that small stocks outperform large stocks because they have more risk, but that’s only because small stocks are priced to reflect this risk. When a market moves toward equal weight, investors are no longer rewarded for taking that risk, and the market becomes inefficient.

Given that Rick’s Waffle Shop is higher risk than the conglomerate, investors should expect to earn a higher return. This assumption is based on a $5 million market cap, not a $250 billion market cap! On the other hand, the conglomerate is underpriced, so the net excess return from the conglomerate would make up for the loss from Rick’s Waffle Shop. It all comes out in the wash in an efficient market.

The market in aggregate only produces a finite amount of profit or loss for all investors to share. Coming up with alternative weighting schemes has never produced an extra dime of profit from the market. It’s impossible to get two quarts of milk from a one quart bottle.

Investors earn a cap-weighted return less cost. Bill Sharpe pointed this out in his timeless 1991 article The Arithmetic of Active Management: “Because active and passive returns are equal before cost, and because active managers bear greater costs, it follows that the after-cost return from active management must be lower than that from passive management… Empirical analyses that appear to refute this principle are guilty of improper measurement.”

The frenzy around so-called Smart Beta strategies sometimes leads to the idea that everyone can outperform the market by using alternative weighting strategies. It’s just not true. The laws of economics cannot be overturned. Investors earn a market return less cost. Everything else is marketing.