by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Chief Investment Officer, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

Franklin Templeton Fixed Income CIO Sonal Desai believes that the Fed’s March policy meeting was not as dovish as some commentators and market participants have claimed, and that the Fed is still pragmatic and cautious about inflation and rate cuts. In her view, getting inflation down to 2% will be harder and take longer than Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell expects, and she predicts that rate cuts will come only later—in the second half of the year.

The Federal Reserve’s (Fed) March policy meeting has generated very vocal reactions by commentators and market participants. This time I think the excitement has gone well beyond what the substance of the meeting warranted and tries to read way too much into the Fed’s new economic projections and into Chair Jerome Powell’s words, in my view. Financial markets’ reaction so far, I’m happy to say, has been slightly more muted than on previous occasions when Powell was perceived as dovish.

Let me say one thing up front: I do think this is a dovish Fed, and that Powell’s own preferences are on the dovish end of the monetary committee. But I also think this is a pragmatic Fed, which has already gotten burnt by high and stubborn inflation.

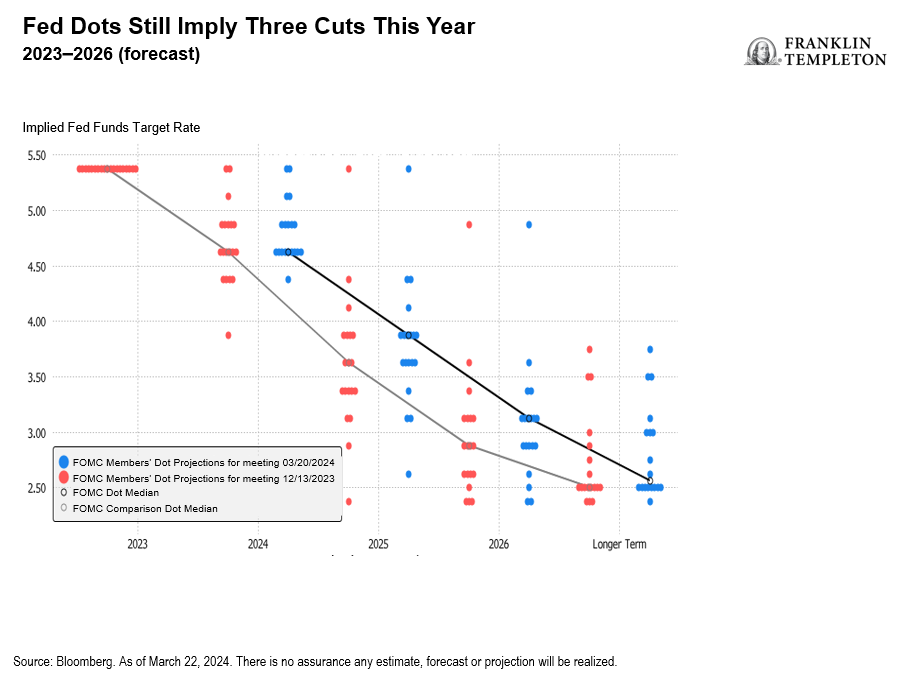

With rates expected to stay on hold, attention focused on the new economic projections. The prevailing narrative about the March meeting has emphasized the fact that the Fed’s new economic projections envision higher inflation and stronger growth, but the median rate forecast implicit in the dots still implies three rate cuts this year. Therefore, the argument goes, the Fed has given a strong signal that it is determined to cut rates and willing to tolerate higher inflation.

But this is one occasion where it’s important to look at the trees, not just the forest: Looking at the individual dots shows that, on net, five governors have reduced their projected number of cuts. Nine out of nineteen members now see two cuts or fewer versus ten who envision three or more (with only one expecting more than three). If just one more governor had lowered a dot, the median would have ticked down to only two rate cuts, and the narrative would have changed.

Next, let’s consider what Powell said during the press conference.

On financial conditions: This commentary was by far the most dovish signal. In the Q&A, Powell pointed to the tentative weakening in labor markets to argue that financial conditions were pushing in the right direction, helping the disinflation effort. This is rather a stretch: Financial conditions as measured by the Bloomberg index are currently as loose as when policy interest rates were at zero. The sustained rally in asset prices has been moving with full force against the Fed’s monetary tightening. Powell was obviously reluctant to utter words that might cause equity markets to retrace, but I think here he pushed the argument too far.

On inflation, Powell to me sounded fairly balanced and pragmatic—by his standards. He did say there are reasons to believe that the higher-than-expected inflation readings of January and February might be “bumps in the road,” partly influenced by seasonal factors. But he acknowledged that within the Federal Open Market Committee the readings certainly did not bolster anyone’s confidence that the disinflation goal is within reach, and that they validated the Fed’s decision to keep rate cuts on hold for longer. He noted that the Fed always expected the disinflation process to be bumpy; it did not get too excited when inflation readings were better than expected, and it’s not panicking after the latest readings—it wants more data to understand whether January and February were “bumps” or signs that inflation is getting entrenched above target.

On policy rates, he reiterated that the Fed sees the first rate cut as a “very consequential” step: The Fed knows there is a risk in waiting too long, but they also still see a risk of cutting too soon. Before they start cutting, they want to be confident that disinflation is sustainably on track, and the strong economy affords them the luxury to wait for more inflation data to come in.

All this sounds sensible. I also have some sympathy for a central bank that finds itself in a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation with respect to the election calendar. With the presidential ballot looming in November, either a sharp downturn in growth or a resurgence in inflation would be highly consequential. And the closer we get to an election, the more likely that a rate cut will be read through a political lens.

I still believe that getting inflation all the way down to 2% will be harder and will take longer than Powell would like—and the Fed’s new projections confirm that some Governors are also getting somewhat more concerned that inflation might prove stubborn. The Fed’s estimate of the neutral policy rate, which inched up to 2.6%, remains well below my estimate of around 4%, but Powell at least acknowledged that rates are unlikely to move back to their post-pandemic lows. And the dots now show one fewer rate cut in 2025—three rate cuts, in line with my view.

So, overall, I think Powell handled the March press conference well, and much of the subsequent debate has been overblown. As I said, it is telling that the market’s reaction has been much more muted relative to previous occasions when Powell was perceived as dovish. But I also remain of the view that the last mile of disinflation will be harder and will take longer. As we get closer to June, where the market is pricing the first rate cut as most likely, this challenge will likely bring more volatility. Neither the data nor Powell’s press conference have changed my view that rate cuts will come only later, in the second half of the year.

Copyright © Franklin Templeton Fixed Income