by Hubert Marleau, Market Economist, Palos Management

December 9, 2022

Wall Street dodged a bullet last week and everybody was expecting a non-eventful session. The data docket was sparse and Fed officials were in a pre-meeting quiet period ahead of this year’s final policy gathering. Not much was supposed to happen in the market. The job market was doing well, the economy chugging along and inflation receding. Put simple, the business was holding strong.

Unfortunately, circumstances changed drastically on Monday when Nick Timiraos, known as the Fed’s whisperer, suggested in the WSJ that Federal Reserve officials could signal on December 14 a higher peak for the policy rate next year than the 5% that they projected last September in their Summary of Economic Projections. Investors desperately wanted to see a market bottom, they did not like that one bit. Knee-jerk reactions based on a single solitary story have become a habit because the market is still sitting on pins and needles. There are also concerns that the Fed will raise rates if there is too much good news, and that bad news will push the economy into a recession. In other words, both good and bad news is bad. Plus the timing of Timiraos’ story made things worse on three additional counts.

First, the Bank of International Settlement (BIS) put investors on guard. It pointed out that non-bank financial firms have more than $80 trillion of hidden off-balance sheet dollar debt in foreigh exchange swaps and forwards, which it described as a “blind spot” that risked leaving policymakers in a thick fog. Gillian Tett, in a FT opinion piece, correctly pointed out that in a world of geopolitical risks, economic pain and challenges to the US currency’s supremacy, transparency is essential.

Second, there were a lot of ed-ops surrounding the potential of a U.S. government debt crisis. The amount of money the Treasury needs to refinance is shockingly large, coming to $9.0 trillion - about 29% of its total outstanding debt of $31.3 trillion. And that amount does not include $1.0 trillion for QT and $2.0 for the anticipated federal deficit.

Third, the November ISM services index unexpectedly jumped, suggesting that Amricans were not ready yet to preserve the remaining stock of their excess savings. They will soon, per my last 4 weekly commentaries.

Meanwhile the shift in China’s Covid-19 lockdown policy, including pledges to focus on stabilising growth and improving consumer sentiment, helped the market, but not enough to compensate for the aforementioned factors. By the end of the week, the S&P 500 was off 3.4% or 138 points, ending at 3934.

Rising Inflation is in the Rear-View Mirror:

The S&P’s US PMI highlighted; that “A striking development is the extent to which companies are increasingly reporting a shift towards discounting in order to help stimulate sales, which augurs well for inflation to continue to retrench in the coming months, potentially quite siginificantly.”

The NY Fed Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) increased moderately in November, reflecting Chinese delivery times, which related to temporary Covid-19 lockdowns. Improvements in U.S. and Taiwanese delivery times and purchases were observed.

The upward revision in GDP growth, reduced number of hours worked, and shorter workweeks pulled productivity up to 0.8% from 0.3% in Q3, which, in turn, pushed unit labour cost increases down to 2.4% from 3.5%. According to the Atlanta Fed, which tracks wages published in job postings, wage growth is on track to fall back to its 3-4% pre-pandemic pace by the second half of 2023.

Meanwhile, the price of Brent crude touched its lowest level in a year, falling below $80 per barrel, which is 40% lower than it was at its peak last March. At that time, the global oil bills accounted for 5.25% of worldwide GDP in nominal terms compared to 2.7% today. Consequently, prices at the pump, the most visible symbol of inflation for much of the year, are now lower than they were a year ago. This reversal is deflationary because crude prices are lower but also pro-growth because it frees income.

Chinese November CPI was up 1.6% y/y. It was down 0.2% m/m for a 3-month annualised rate of 0.8%. Meanwhile, producer prices were down 1.3% y/y.

U.S. November producer prices - supply-side price data - were up 7.4% y/y, a slowdown from 8.1% in the previous month and 11.7% at the March high. The month data was up 0.3%, giving a 3-month annualised rate of 3.2 %..

The Cycle of Interest Hikes Is Slowing and Coming Close to a Terminal Rate:

The Reserve Bank of Australia raised rates on Tuesday by 25 bps, warning that more hikes were to come; while the Bank of Mexico mentioned that, although the rhythem of interest rate increases will slow, more hikes can still be expected. Meanwhile, the Bank of Canada followed suit on Wednesday with a 50 bps increase in the bank rate to 4.25%. It took the lead among the major G10 central banks announcing a step down last October and is now the first one again to say that considerations will be given to whether the policy rate needs to rise further. If one eliminates posturing, the Bank's next move will be to pause. Andrew Lees points out: “It is worth remembering that 3-months annualised CPI has been 2% or lower for the past 3 months.”

The Canadian policy rate is now 125 bps above the neutral rate. If that gap were to hold up for a while, a better balance between supply and demand can be expected to return inflation closer to target. Fed Chairman Powell is not beholden to Tiff Macklem, the Governor of the Bank of Canada, but he’s not likely to ignore the dovish surprise of a lesser important central bank and risks missing a nuance that might well be relevant.

Goldman Sachs says: “This Time Is Different”: Stepping Out with the Herb.

The much-predicted recession is priced in. If the economy shrinks next year, no one should be surpised. It’s the most widely forecast recession in history. Professional forecasters surveyed by the Philly Fed showed that the average probability of such an outcome is about 50% - never been that high - and it's based on the notion that good news is bad. Meanwhile, a recent WSJ survey found that economists think there is a 63% chance of a recession next year. In a December survey conducted by the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago in partnership with the Financial Times, 85% of economists said they expected the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) - the arbiter of recession - will declare one by next year.

This does not mean that they are right. The record taken as an average is awful - not a single recession was spotted in advance. They missed the 1990, 2001 and 2008 recessions completely.

Goldman Sachs (GS) is not buying the hard landing forecast, arguing that “this time is different”, perhaps a dangerous assumption. Nevertheless, Jan Hatzius, chief economist at GS, puts the risk of a recession at 35%. That is out of step with the herb. Here is the argument in a nutshell: He’s calling for a “soft landing”, narrowly avoiding a recession as core PCE inflation slows from 5% now to 3% in late 2023, with a half-a-point rise in the unemployment rate to 4.2%. Why? There are three basic reasons to believe that this cycle is different and that a soft landing is in the cards.

“First, the over-hot jobs market has shown up in ‘unprecedented job openings’, which are much less painful than over-hiring to unwind. Second, there’s still more disinflation to come as supply chains and housing markets normalise. Third, long-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored.” (Financial Times)

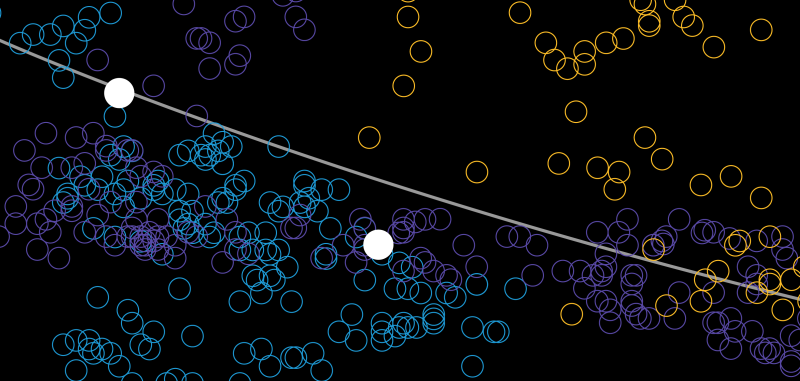

This would be huge, if it were to happen. It would protect earnings from falling too much and allow the Fed policy makers to pause also and at some point cut rates. It may be a reason why the Dow Jones Industrial index is on the verge of forming a technically bullish golden-cross. It occurs when a shorter-term moving average over a major long-term moving average to the upside. Interestingly, since the post-WW11 era, only two periods of back-to-back negative S&P 500 returns have come to pass.

For all this to happen, three things must go right:

- Inflation must come down on its own, not because demand collapses.

- The Fed needs to recognise in time that it doesn’t need to crush demand to get what it wants.

- The sharp rise in interest rates does not cause a recession.

Copyright © Palos Management