2Q S&P500 Corporate Results Survey: All-Time High Sales, Profits, and Margins

by Urban Carmel, The Fat Pitch

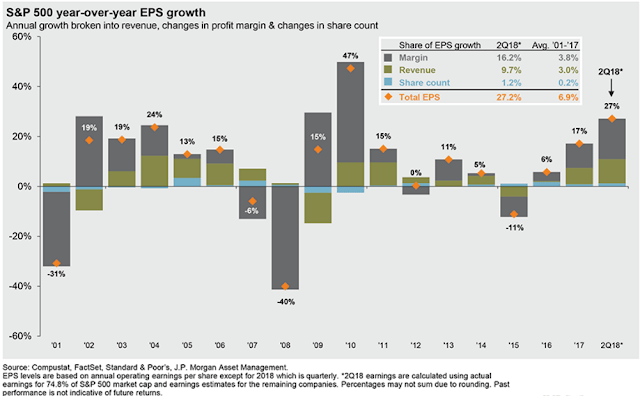

Summary: Overall, corporate results in the second quarter were excellent. S&P sales grew 11%, earnings rose 27% and profit margins expanded to a new all-time high of 11.4%.

Fundamentals are driving the stock market higher, not valuations: earnings during the past 1 year and 2 years have risen faster than the S&P index itself. The strong growth in company profits is not due to the net reduction in shares through, for example, corporate buybacks.

The outlook in 2018 looks solid: the consensus expects earnings to grow 21% this year. Rising energy prices and the tax reform law are tailwinds.

Expectations for 10% earnings growth in 2019 looks too optimistic and will likely be revised downward; the substantial jump in margins this year is unlikely to be sustained, especially with labor and interest expenses rising.

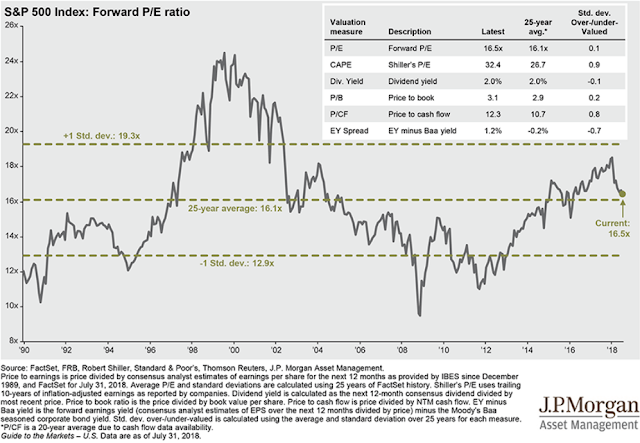

Valuations are back to their 25-year average. They are not cheap, but the excess from 2017 and early 2018 has been worked off. If investors once again become ebullient, there is room for valuations to expand.

90% of the companies in the S&P 500 have released their second quarter (2Q18) financial reports. The headline numbers are very good. Here are the details:

Sales

Quarterly sales reached a new all-time high, growing 11% over the past year, the best sales growth in 7 years (since 2011). On a trailing 12-month basis (TTM), sales are 9% higher yoy (all financial data in this post is from S&P). Enlarge any image by clicking on it.

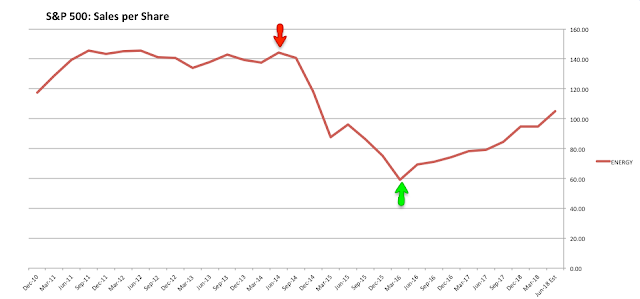

The arrows in the chart above indicate the period from 2Q14 to 1Q16 when oil prices fell 70%. The negative affect on overall S&P sales (above) and the energy sector alone (below) is easy to spot.

In the past year, the six sectors with the highest weighting in the S&P have grown an average of 10.2% (box in middle column) and since the peak in oil in 2Q14, their sales have grown an average of 27.8%. In contrast, energy sector sales have declined 25% (far right column).

The arrows again indicate the period when oil prices fell 70%. The new high in total EPS comes with energy sector EPS at half of its level in 2014.

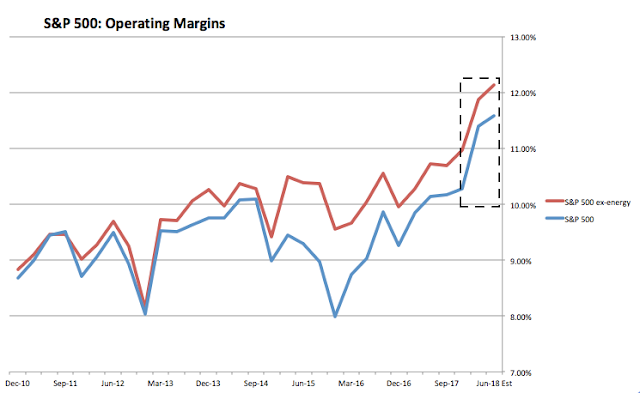

Likewise, overall S&P profit margins peaked at 10.1% in early 2014, fell to 8% at the end of 2015 and have since rebounded to new highs of 11.4% in 2Q18.

For most sectors, margins remained relatively stable while energy fell and rebounded in 2014-16. But in the past 6 quarters, non-energy margins have expanded from 9.9% to 12.1%.

Misconceptions and Bad Memes

There are some common misconceptions that are regularly cited with respect to corporate earnings.

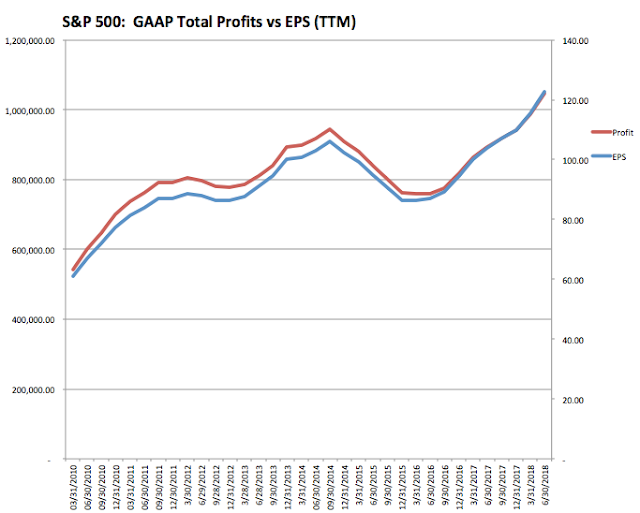

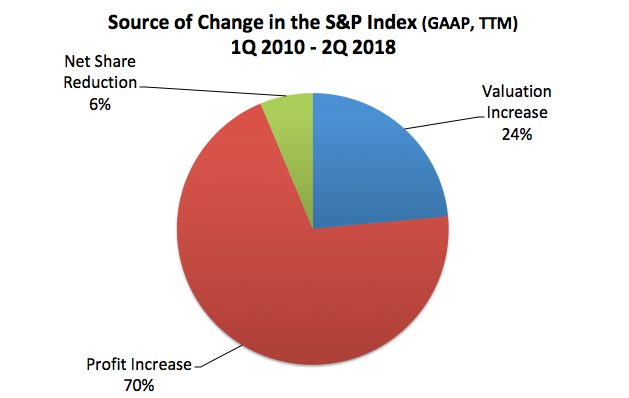

First, companies have been accused of inflating their financial reports through a net reduction in shares through, for example, corporate buybacks. In reality, however, over 90% of the growth in earnings in the S&P over the past 8 years has come from better profits, not a net reduction in shares. Better profits drive growth, not "financial engineering."

That has been true over the past 17 years, during which the change in corporate shares has accounted for just 3% of EPS growth (from JPM).

In fact, the impact of share reduction has declined over the past two years as the difference between EPS and profits has markedly narrowed.

Second, equity prices are said to have far outpaced earnings during this bull market. In fact, better profits accounts for about 70% of the appreciation in the S&P over the past 8 years. Of course valuations have also risen - that is a feature of every bull market, as investors transition from pessimism to optimism - but this has been a much smaller contributor. In comparison, 75% of the gain in the S&P between 1982-2000 was derived from a valuation increase (that data from Barry Ritholtz).

Over the past 2 years (since 2Q16), during which time the S&P has risen about 30%, earnings have risen 41%, i.e., faster than the S&P index itself thereby accounting for more than 100% of price appreciation. The same is true over the past 1 year.

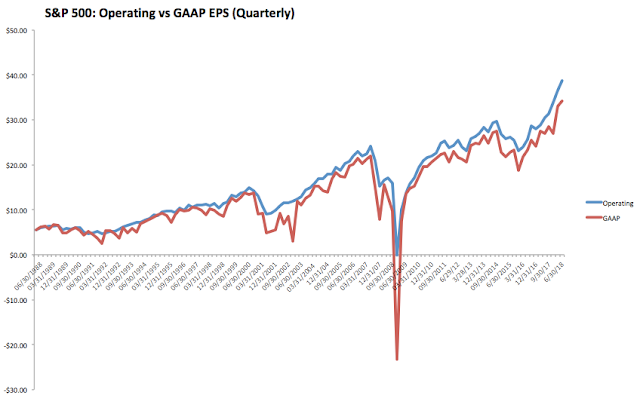

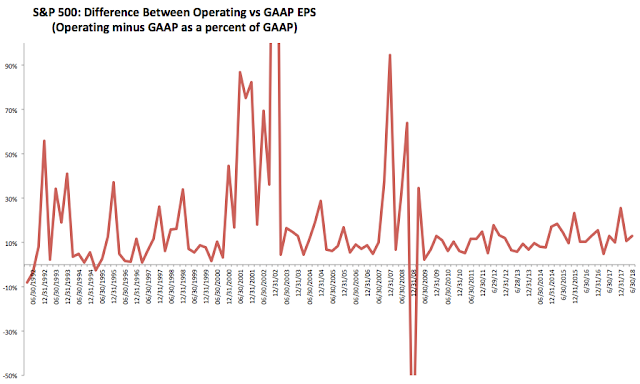

Third, financial reports based on "operating earnings" are said to be fake. This complaint has been a feature of every bull market since at least the 1990s. In truth, the trend in GAAP earnings (red line) is the same as "operating earnings" (blue line).

It's accurate to say that operating earnings somewhat overstate and smooth profits compared earnings based on GAAP, but that is not new. In fact, the difference between operating and GAAP earnings in the past 25 years has been a median of 10% and the recent history has been no different (it was 13% in the most recent quarter). Operating earnings overstated profits by much more in the 1990s and earlier in the current bull market. The biggest differences have always been during bear markets.

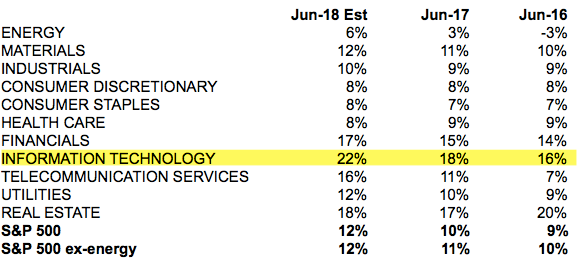

Looking ahead, the consensus expects 21% earnings and 8% sales growth in 2018 (from FactSet). There are four considerations with a strong bearing on forward sales and earnings.

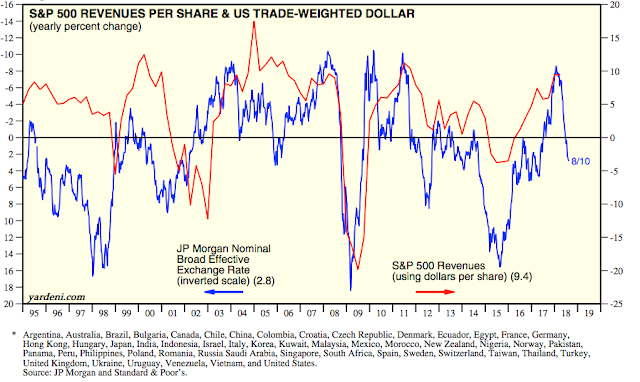

First, as a baseline, it is reasonable to assume that corporate (non-energy) sales growth will be largely similar to the nominal economic growth rate of 4-5%, excluding currency effects (from the OECD).

Second, the dollar weakened in 2016-17 (a tailwind to growth) but is tracking close to flat for 2018. That means that currency effects are no longer a tailwind to growth. With half of corporate sales coming from abroad, a small 2-4% appreciation in the dollar could cut 1-2 percentage point to sales growth in the next year (second chart from JPM).

Third, the price of oil is tracking a healthy 28% yoy gain so far in 2018, meaning the energy sector should continue to be a tailwind to overall corporate sales and EPS growth.

As we have seen, the direct impact of oil prices on the energy sector is far more important than any ancillary affects on other sectors. As an example, consider this: the price of oil fell from over $100 to under $50 between mid-2013 and mid-2016 but non-energy sector operating margins were 10% in both instances.

Finally, corporate tax cuts have been a major tailwind to earnings. Analysts estimate that these likely add 10 percentage points to growth, meaning baseline growth of 5% jumps to 15% by virtue of tax cuts alone.

The tax cut is a one-off adjustment, applicable only to 2018, and there is not much reason to expect it to permanently raise growth rates. Why? US corporations are not capital constrained; they have abundant cash and access to low cost debt and equity. Moreover, corporations have been making fixed capital investments. Over the past 3 decades, rising corporate profitability (blue line) has had no positive affect on new investments (red line; from the FT).

Outlook for 2019: Peak Margins?

Next year, the consensus expects 10% earnings and 5% sales growth (from FactSet). Sales growth expectations are fine but the expected earnings growth looks too optimistic.

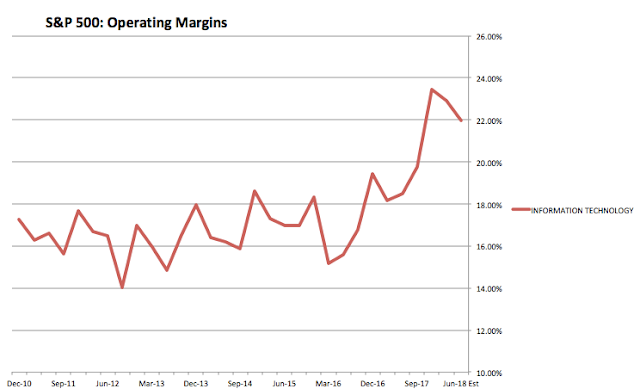

The primary reason for skepticism is margins. For earnings to grow faster than sales, margins have to expand. But after trending higher over the past 7 years, margins expanded by 130bp in the past two quarters. This is a massive jump and sustaining that level (let alone expanding margins further) is too aggressive an assumption, especially in face of rising labor and interest expenses.

All else equal, an approximate guess would be that earnings in 2019 will grow no faster than sales (5%). If the dollar continues to appreciate, that growth could drop to just 3%.

Valuation

Corporate growth should be a tailwind for equities in 2018 and perhaps (to a much smaller degree) in 2019 as well. With the relatively minor appreciation in equity prices so far in 2018, valuations are back to their 25-year average (from JPM).

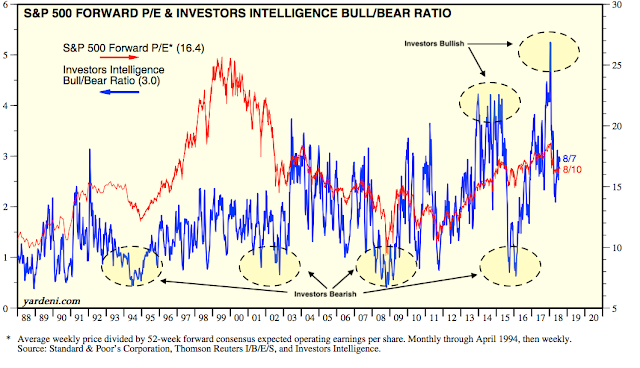

Valuations are not cheap, but if investors once again become ebullient, there is room for valuations to expand. Why? When investors become bullish (blue line), valuations rise (red line). Investors had been pessimistic in early 2016 and then became far too optimistic at the market peak in January 2018. That had been largely reset by 2Q18. With the ongoing rally, optimism is once again rising but is not yet at a bullish extreme (from Yardeni).

Valuations are influenced by more than investor psychology. Part of the reason equities have become more expensive over time is rising corporate profitability. Margins have reached successive new highs with each economic cycle over the past 3 decades: they are now more 100bp higher than in 2007, and that peak was more than 100bp higher than in 2000. Higher profitability (and growth) is typically rewarded with higher valuation multiples (from Yardeni).

Again, while it is objectively impossible to know when or at what level margins will peak for this cycle, it's a reasonable guess that significant further upside is probably limited.

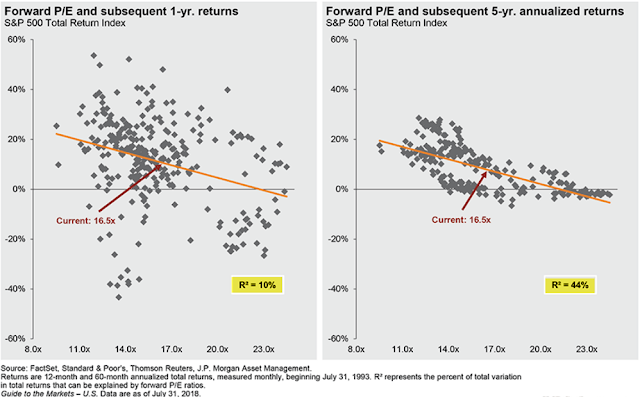

Importantly, valuations have almost no bearing on the market's 1-year forward return (left side). But over the longer term, current valuations suggest that single digit annual returns are odds-on (right side; from JP Morgan).

In summary, corporate results in the second quarter were excellent. S&P sales grew 11%, earnings rose 27% and profit margins expanded to a new all-time high of 11.4%.

Fundamentals are driving the stock market higher, not valuations: earnings during the past 1 year and 2 years have risen faster than the S&P index itself. The strong growth in company profits is not due to the net reduction in shares through, for example, corporate buybacks.

The outlook in 2018 looks solid: the consensus expects earnings to grow 21% this year. Rising energy prices and the new tax reform law are tailwinds.

Expectations for 10% earnings growth in 2019 looks too optimistic and will likely be revised downward; the substantial jump in margins this year is unlikely to be sustained, especially with labor and interest expenses rising.

Valuations are back to their 25-year average. They are not cheap, but the excess from 2017 and early 2018 has been worked off. If investors once again become ebullient, there is room for valuations to expand.

Copyright © The Fat Pitch