At the top of every cycle, the story feels clean. Growth is strong. Profitability is visible. Market leadership appears rational, deserved—permanent.

In “The peak of conviction: Why every ‘new paradigm’ feels obvious before it fades,” Schroders' Portfolio Manager Dan Suzuki takes readers on a 75-year walk through market history1 to examine a pattern investors rarely recognize in real time: the closer you get to a secular peak, the more compelling the narrative becomes.

He writes:

“Historically, the case for an investment opportunity tends to appear most compelling the closer you get to its peak, when strong growth, high profitability, and stellar past performance attract a widening pool of investors eager to buy into what looks like unstoppable momentum at any price.”

This is not a critique of innovation. It is a critique of valuation, conviction, and crowd behavior.

And as Suzuki frames it, secular investment stories are particularly dangerous because they often masquerade as structural inevitabilities:

“Secular investment opportunities are particularly pernicious in that they often appear under the guise of a ‘new paradigm,’ driven by innovation or structural shift.”

The longer the cycle runs, the more inevitable it feels. The more extended the leadership, the more the past appears to validate the future.

To understand today’s debate—US tech dominance and AI leadership—Suzuki revisits the defining “new paradigm” stories of the past.

The Pattern of Peak Obviousness

Late 1960s: The Nifty 50 — “One-Decision Stocks”

The narrative: Fifty dominant US large-cap companies—GE, Coca-Cola, IBM—leveraged brand strength and scale to expand relentlessly. Their growth was rapid. Their profitability strong. Their competitive moats deep.

Valuations exceeding 30–40x earnings were justified by investors who believed these companies were permanent compounders.

They became known as:

“one-decision stocks”: you bought them once and never had to think about selling.

What happened next: High inflation and rising interest rates in the early 1970s crushed earnings growth. The Nifty 50 crashed, launching a two-decade stretch of US underperformance versus international markets.

Even great companies can be terrible investments when purchased at peak conviction.

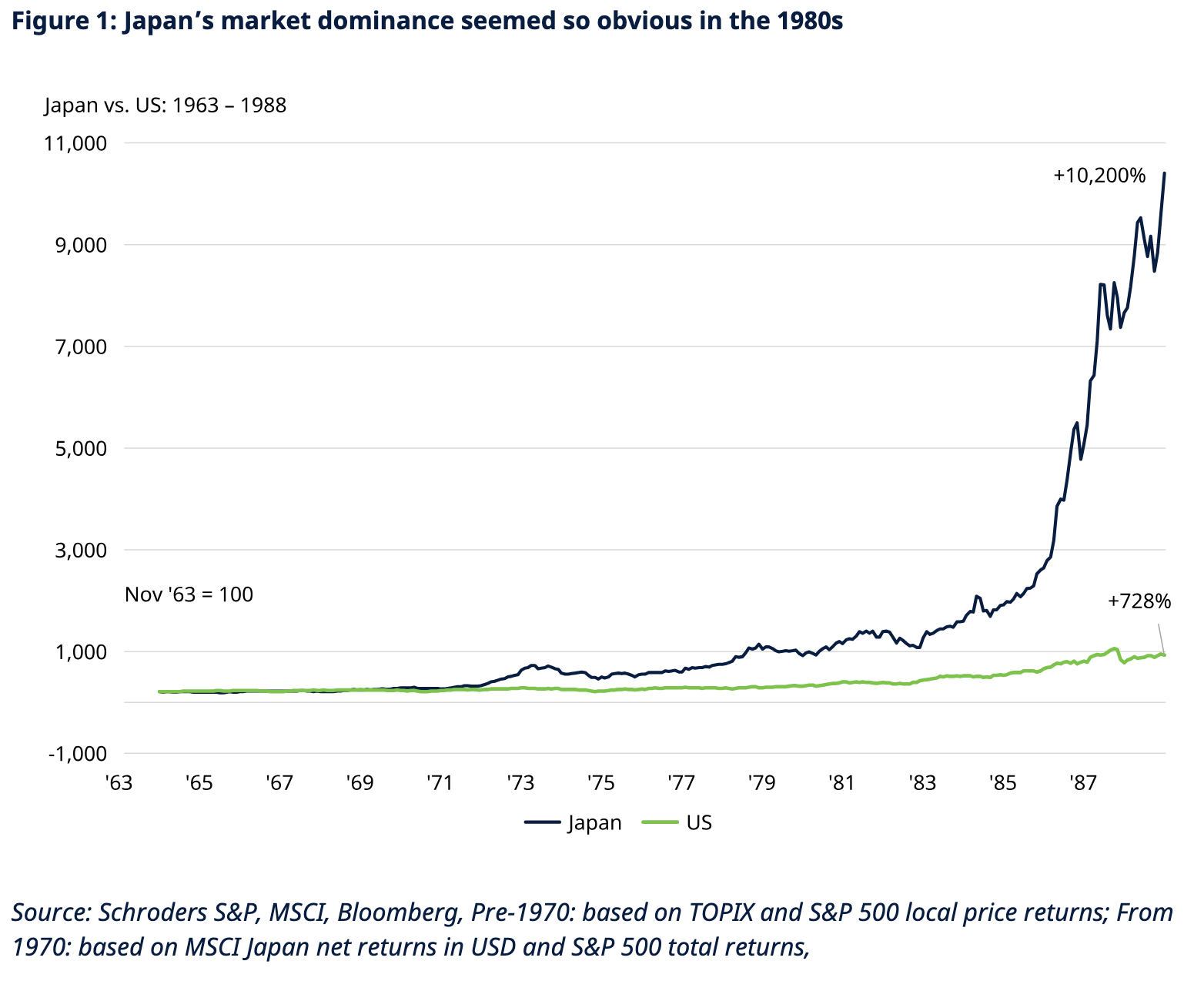

Late 1980s: Japan Owns the Future

The narrative: Japan dominated autos, electronics, and manufacturing efficiency. It held 45% of global market capitalization. Its companies appeared technologically superior.

So inflated were valuations that:

“the land beneath the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth more than all the real estate in the state of California.”

What happened next: A liquidity crunch—stronger currency, higher rates, tighter lending—triggered a collapse in equities and real estate. It took 34 years for Japanese stocks to reclaim their 1989 peak.

Liquidity, not narrative, determines outcomes.

Late 1990s: The Internet Changes Everything

The narrative: The US dominated the internet revolution. Globalization reduced costs. The government ran a budget surplus. Investors rushed to buy:

- PC and chip producers

- Telecom infrastructure

- Online retailers

- ISPs

The future was digital—and everyone knew it.

What happened next:

“Even as internet adoption continued to accelerate, internet stocks crashed as fundamentals failed to keep pace with ever-rising expectations.”

The NASDAQ fell more than 80%. It took 15+ years to recover.

This distinction is critical:

The internet was real. The productivity gains were real. But the price paid was too high.

2007: China Becomes the World’s Factory

The narrative: After joining the WTO in 2001, China grew at double-digit GDP rates—roughly four times US growth. Investors were drawn to expanding wealth and profit acceleration.

What happened next:

“Like past supercycles, the story of China’s rise blended genuine structural change with speculative overreach.”

More than 18 years after its 2007 peak, China’s stock market remains below that level—despite the economy having quintupled.

Why?

Unsustainable borrowing. Shadow banking. State intervention. Overinvestment.

Again: Structural progress does not immunize equity investors from overvaluation.

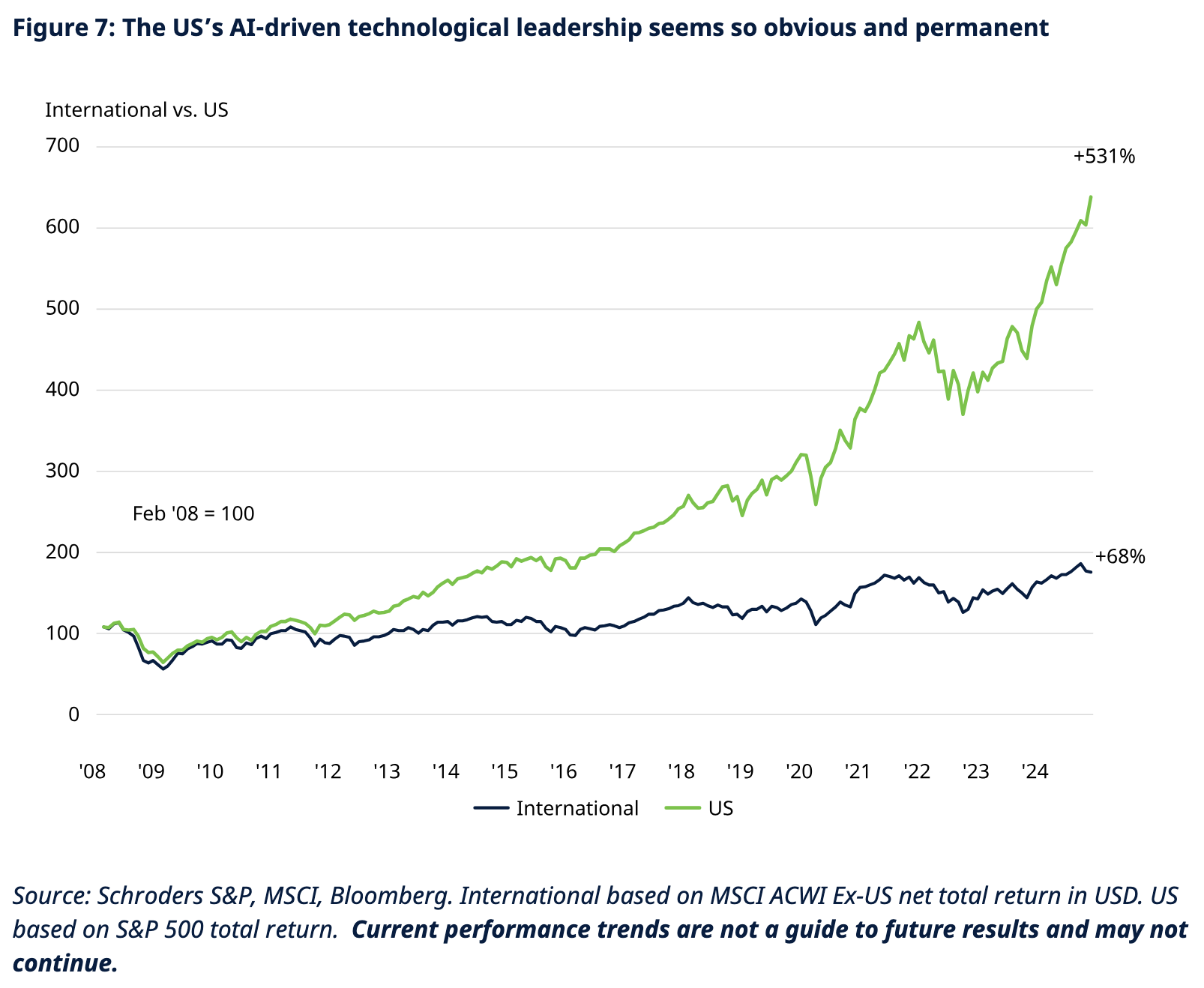

2025: US Tech Takes Over the World

Now we arrive at the present.

The narrative: Since the Global Financial Crisis, US corporate profits have surged. Cheap financing, dominant tech platforms, and AI investment have driven extraordinary outperformance.

Meanwhile:

- Europe endured austerity.

- China faced a property crisis.

- Japan battled deflation.

The US dollar reversed prior weakness by 50%+. US returns dwarfed international markets.

In many investors’ minds, the US became “the only thing worth owning.”

Suzuki acknowledges this is the defining debate of the decade:

“This remains the defining debate of the decade.”

Are we witnessing the early innings of a productivity miracle? Or are valuations embedding growth assumptions that are mathematically difficult to achieve?

He frames the tension directly:

“Bulls argue we are in the early innings of a technology-driven productivity miracle that will rewrite the global economy. Skeptics point to the math of elevated valuations and unattainable growth expectations.”

Then comes the historical insight:

“History suggests both can be right, but on different timelines.”

Innovation may continue. But returns can disappoint for a decade if expectations overshoot reality.

The Behavioral Trap: Chasing Hindsight

Suzuki identifies the recurring behavioral mistake:

“The issue is that investors chase hindsight, piling into assets based on stellar past performance exactly when the risks are greatest.”

At cycle peaks:

- Diversification is abandoned.

- Leverage increases.

- Risk management feels unnecessary.

- Concentration appears rational.

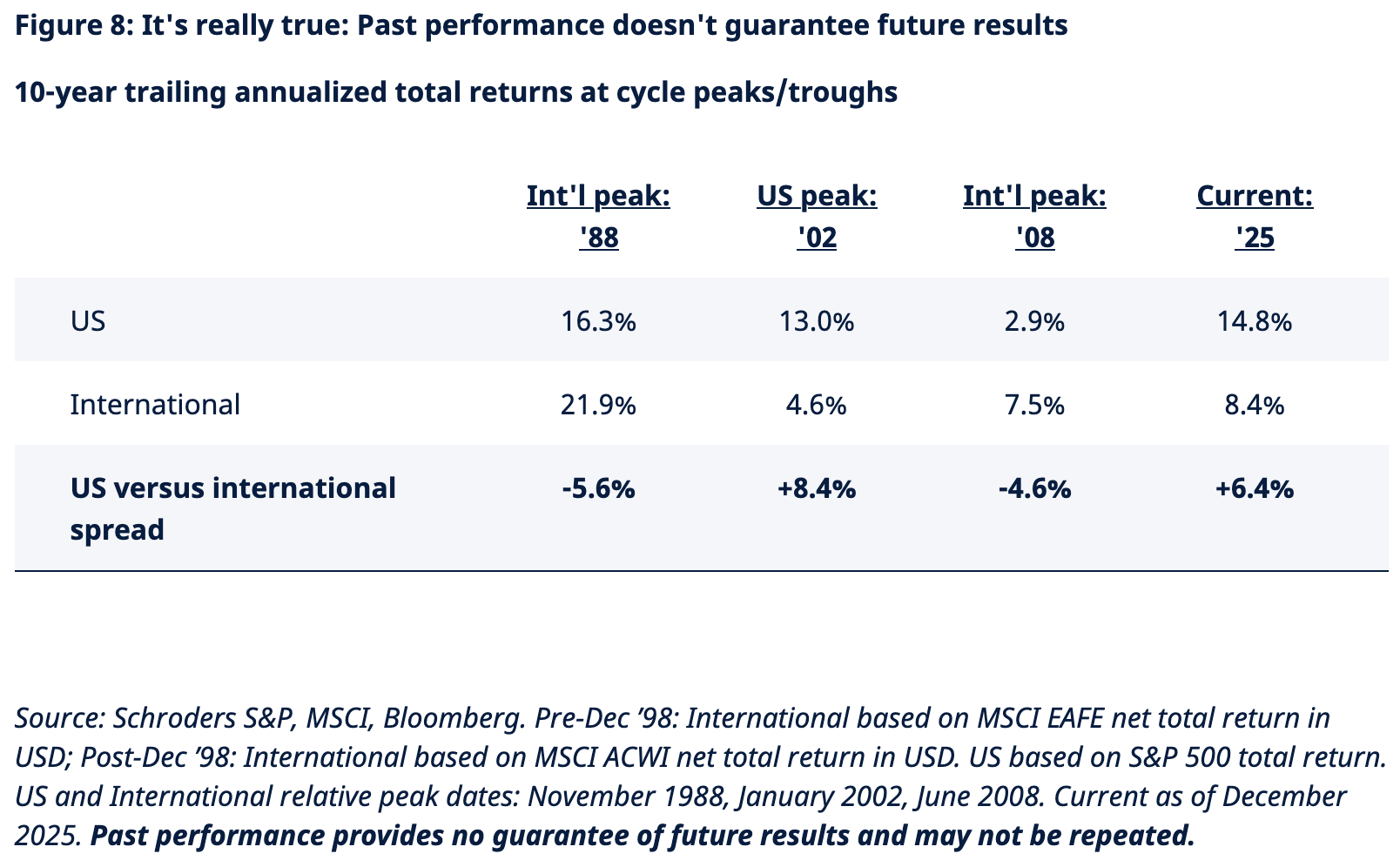

Figure 8 reinforces the pattern: 10-year trailing returns at cycle peaks often represent the high-water mark before underperformance begins.

This is recency bias institutionalized.

Every Boom Has Its Bust

Suzuki’s conclusion is not dramatic—it is measured, historical, disciplined:

“What felt like a revolutionary ‘new paradigm’ for society and markets ultimately revealed itself as just another market cycle.”

And the most important warning:

“The takeaway: when a theme becomes ‘so obvious,’ it’s worth pausing to consider the risks that may be underpriced in market expectations.”

Late-cycle cracks rarely appear suddenly. They form through:

- Disappointing growth

- Overinvestment

- Emerging competition

- Liquidity tightening

The proactive investor does not wait for the crack.

“Rather than waiting for cracks to emerge, proactive investors might consider pivoting now, exploring diversification beyond the crowd’s favorites to build resilience for whatever comes next.”

*****

Key Takeaways for Advisors

1. Obvious Is a Sentiment Indicator

When clients say, “Everyone knows this,” that is not confirmation—it is a signal.

2. Innovation ≠ Immediate Returns

Technology cycles can transform economies while delivering subpar equity returns for a decade.

3. Valuation Discipline Matters Most at Peaks

Elevated expectations embed fragile math.

4. Diversification Is Most Valuable When It Feels Unnecessary

History’s leaders eventually rotate.

5. Timing Cycles Is Impossible — Preparing for Them Is Not

Resilience, not prediction, is the objective.

For Investors

Suzuki’s framework does not argue against US tech. It argues against peak conviction pricing.

It reminds us that:

- Leadership feels permanent at its height.

- Past performance peaks coincide with maximum consensus.

- Long-term outperformance often follows periods of underownership, not overownership.

Markets reward innovation. They punish inevitability.

And history shows that when something feels “so obvious it hurts,” the pain rarely comes from missing it. It comes from overpaying for it.

Footnote:

1 Dan Suzuki, CFA, et al. Schroders Investment Management. "Decoding Markets: So obvious it hurts." 4 Feb. 2026.

https://www.schroders.com/en-us/us/intermediary/insights/decoding-markets-so-obvious-it-hurts/