In markets today, one question looms large: Are we at a peak — or merely somewhere on the slope toward it? It’s a question investors — and especially advisors — must confront. Because at such heights, as Henry Neville wryly observes, “falling … will kill you.”

His note, Such Great Heights: Lessons from 59 Peaks1, isn’t a flash forecast or a “sell everything” screed. It’s a disciplined data-anchored investigation into what past peaks have looked like — and what that might imply for today’s market environment. In true Man Group “Road Ahead” fashion, Neville places systematic evidence over narrative, grounding his look at peaks in patterns rather than panic.

1. The Anatomy of a Peak: 59 Episodes Over a Century

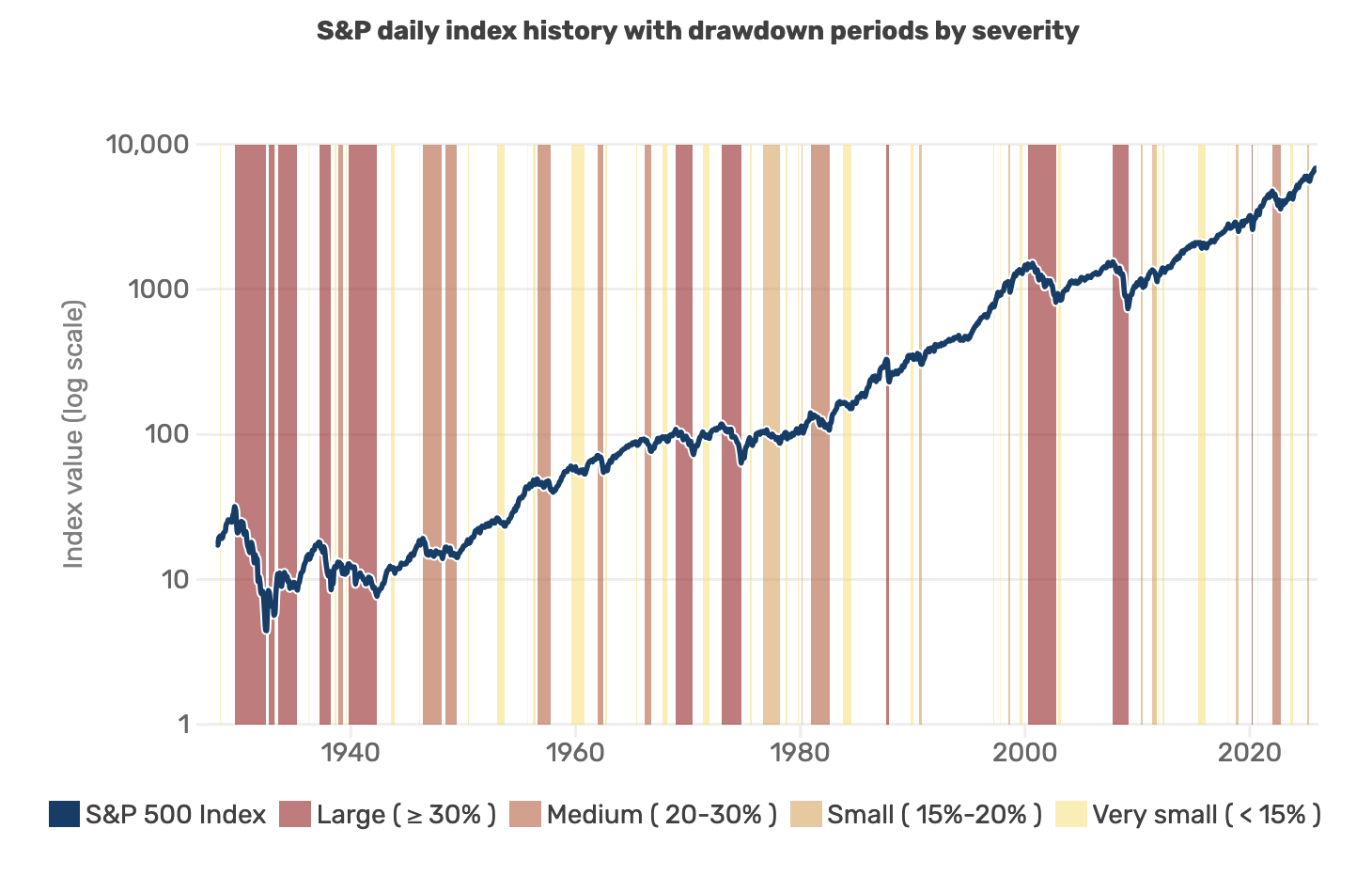

The central contribution of the piece is its empirical scope. Neville compiles 59 drawdown episodes over the last 100 years, using definitions from both Man Group and Morgan Stanley.

He notes up front that a key driver of the analysis is defining the event itself — not merely asking “is this a peak?” but “what counts as a drawdown?”

Source: Man Group defined drawdowns, compared against a similar list from Morgan Stanley, Bloomberg. As of December 2025.

This matters. Financial markets are noisy by nature, and:

- Investors tend to latch onto neat numerical thresholds — e.g., “a 10% decline is a drawdown” — even when the real world is less cooperative.

- Neville acknowledges this: “Defining with less granularity is, ultimately, a form of hindsight bias.”

From that disciplined base, two patterns emerge:

Base-Rate Patterns (Timing)

- “History suggests we can expect a peak every two years and a major peak every nine years.”

- This cadence of peaks is useful in itself — not as a precise clock, but as a signal that volatility and regime shifts are normal parts of market life, not aberrations.

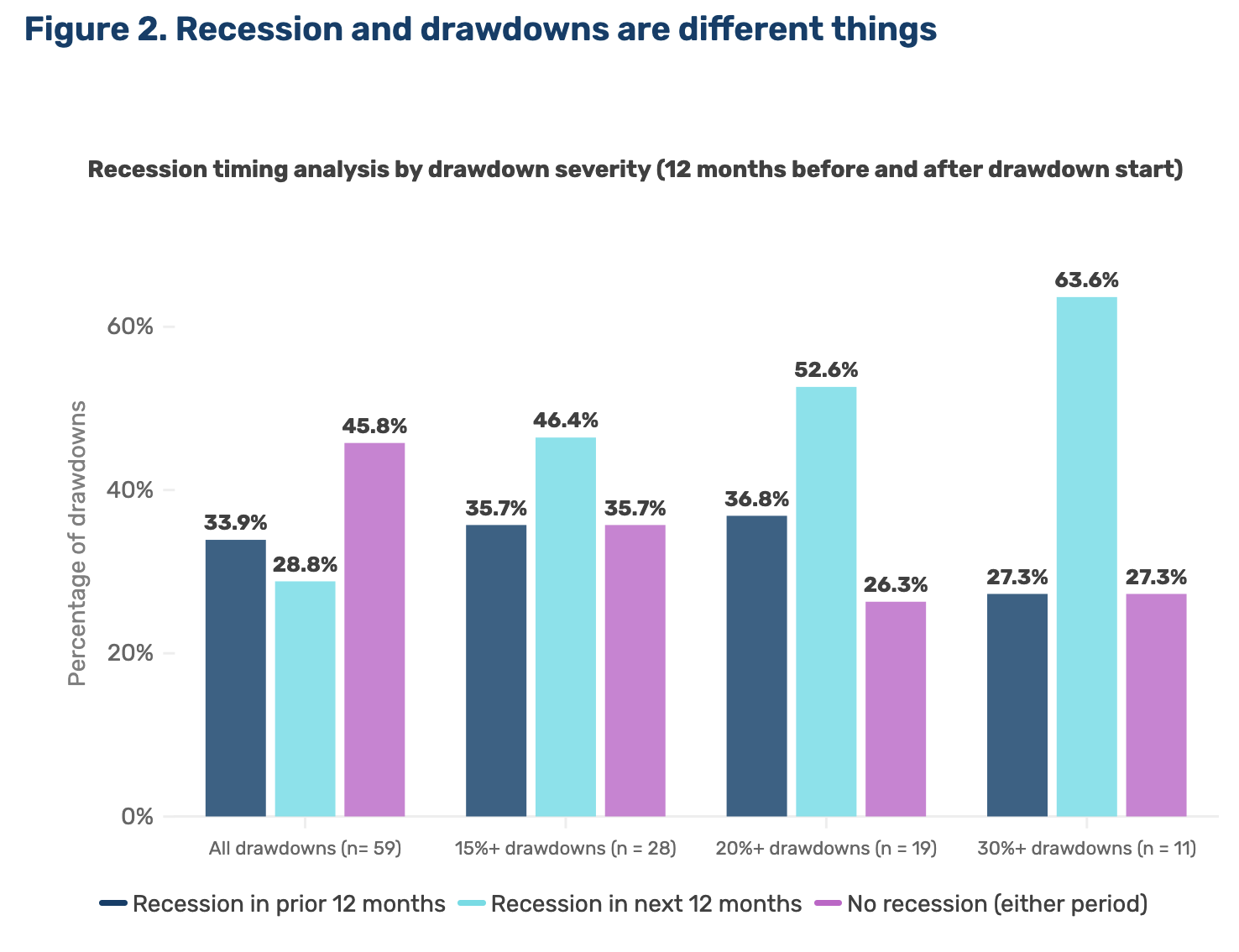

2. Disconnect Between Markets and the Economy

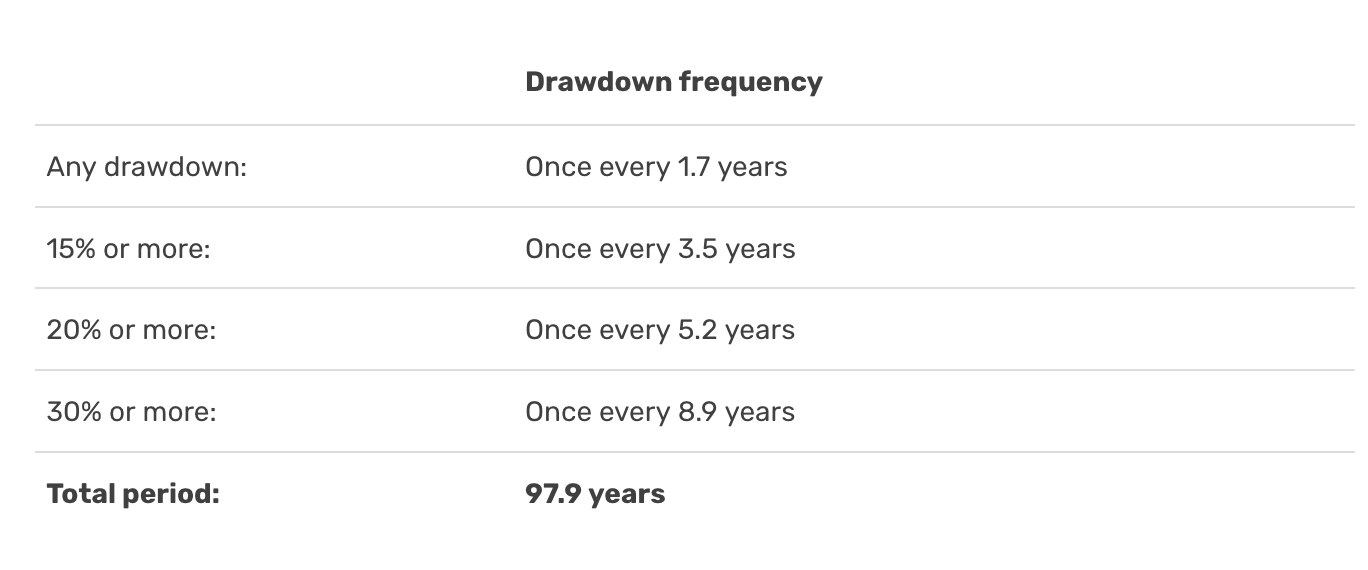

Contrary to the common narrative that major sell-offs are tethered to economic recessions, Neville surfaces a surprising statistical separation.

- Nearly half of all drawdowns did not occur in the context of a recession, before or after.

- Even among the 11 largest sell-offs (>30%), three had no recession accompanying them.

This distinction is more than a curiosity — it reframes how advisors should think about risk:

Market events are not merely reflections of economic events.

Three specific episodes — pre-World War II decline, the late-1960s stock bubble bust, and Black Monday in 1987 — illustrate this divergence.

3. Three Drivers That Do Signal Peak Risk

Neville’s core contribution isn’t a binary peak/no-peak call, but rather three market conditions that have historically preceded drawdowns.

A. Volatility: Too Quiet Before the Storm

He finds that low realized volatility often precedes peaks.

-

- “Stability is the midwife of instability … What is true personally also applies to financial markets.”

Today, trailing volatility is meaningfully below average, placing us in what Neville calls the “danger zone”.

Implication: Calm markets are comforting — until they aren’t. Low volatility can lull investors into complacency just as systemic risk is accumulating.

B. Inflation: Too Hot or Too Cold Is Trouble

Markets historically don’t like either extreme:

-

- Hot inflation erodes margin and creates monetary tightening.

- Deflation threatens growth and credit dynamics.

In fact, 73% of the peaks examined occurred when inflation was outside the soft target zone (below 1% or above 2.5%).

Today’s core inflation figures — slightly above the comfort range — are close to that historic pattern.

C. Valuation: Expensive Enough to Matter

Neville explicitly warns that valuation alone isn’t a timing tool, but it does matter for drawdown risk:

-

- In almost three-quarters of episodes, valuations (measured via the Shiller CAPE) were above their three-year average at the peak.

- Today’s Shiller CAPE sits six points above its trailing average.

So markets are not cheap, and when combined with the other two signals, valuation adds fuel to the risk backdrop.

4. Earnings Growth: A False Safety Net

Perhaps most counterintuitively, earnings growth doesn’t tell us much about peaks:

- Real earnings growth was positive in 59% of episodes.

- In more than a third, it exceeded 10%.

In other words, robust earnings do not inoculate markets from drawdowns. Strong fundamentals can simply delay mercy.

5. The Landscape Today: Peak or Plateau?

Neville’s final metaphor captures the essence of the dilemma:

“…we may well be looking down from the 80th floor. But we don’t know whether … we’re at the top … or … only halfway there.”

This is classic GSM2 framing: a high-resolution description of uncertainty without forced conviction.

He reminds us — calmly, but emphatically — that being at height itself is risk in today’s markets.

Key Takeaways for Advisors & Investors

1. Expect Peaks — They Are Normal

Peaks every ~2 years and big peaks roughly every ~9 years aren’t aberrations — they’re the baseline rhythm of markets. Investors should plan around this cadence, not be surprised by it.

2. Economics ≠ Markets

Risk management must separate market dynamics from macro fundamentals. A recession is not necessary for drawdowns — markets often move first, not last.

3. Pay Attention to Conditions, Not Predictions

Markets are high — and three historical patterns (low volatility, inflation extremes, elevated valuations) are all present. That’s not a call to sell everything, but it is a call to sober, proactive positioning.

4. Earnings Are Not a Timing Signal

Good news on profits can mask risk, not eliminate it. Don’t confuse strong earnings with lower downside risk.

5. Positioning Over Prognostication

Neville’s final warning — that any fall from high altitude will hurt — isn’t a forecast. It’s a risk framework. Advisors should integrate risk buffers, scenario planning, and diversified hedges rather than rely on a binary peak call.

Conclusion

In Such Great Heights, Henry Neville offers investors a rarer breed of market commentary — one rooted in history, shaped by data, and unafraid to embrace uncertainty without surrendering rigor. In a world where most calls are either bullish or bearish, this is the kind of realistic, context-rich analysis that advisors can build strategies around — not simply react to headlines.

At such heights, comfort in complacency is more dangerous than discomfort in caution.

Footnote:

1 Neville, Henry. Man Group. "The Road Ahead. Such Great Heights: Lessons from 59 Peaks | Man Group." 17 Feb. 2026.