by Eric Winograd, Sandra Rhouma, Eric Liu, AllianceBernstein

We expect economic growth to continue in 2026, but wide-ranging factors will influence the patterns.

As 2026 moves closer into view, the global economy should continue to produce moderate growth. However, there are areas of concern underneath our baseline forecast, notably from frictions in the US expansion. Globally, the new tariff regime has re-routed trade flows and—as always—investors should brace for a healthy dose of the unexpected.

A Resilient Economy…but Imbalances Under the Surface

The world economy was resilient in 2025, expanding despite dramatic policy changes and a host of geopolitical risk events. We expect growth to continue in 2026, though the rate will likely stay below the long-run average. As we see it, the range of possible outcomes has narrowed from a year ago: the probability of a significant downturn is lower and so is the risk of a significant inflation pickup.

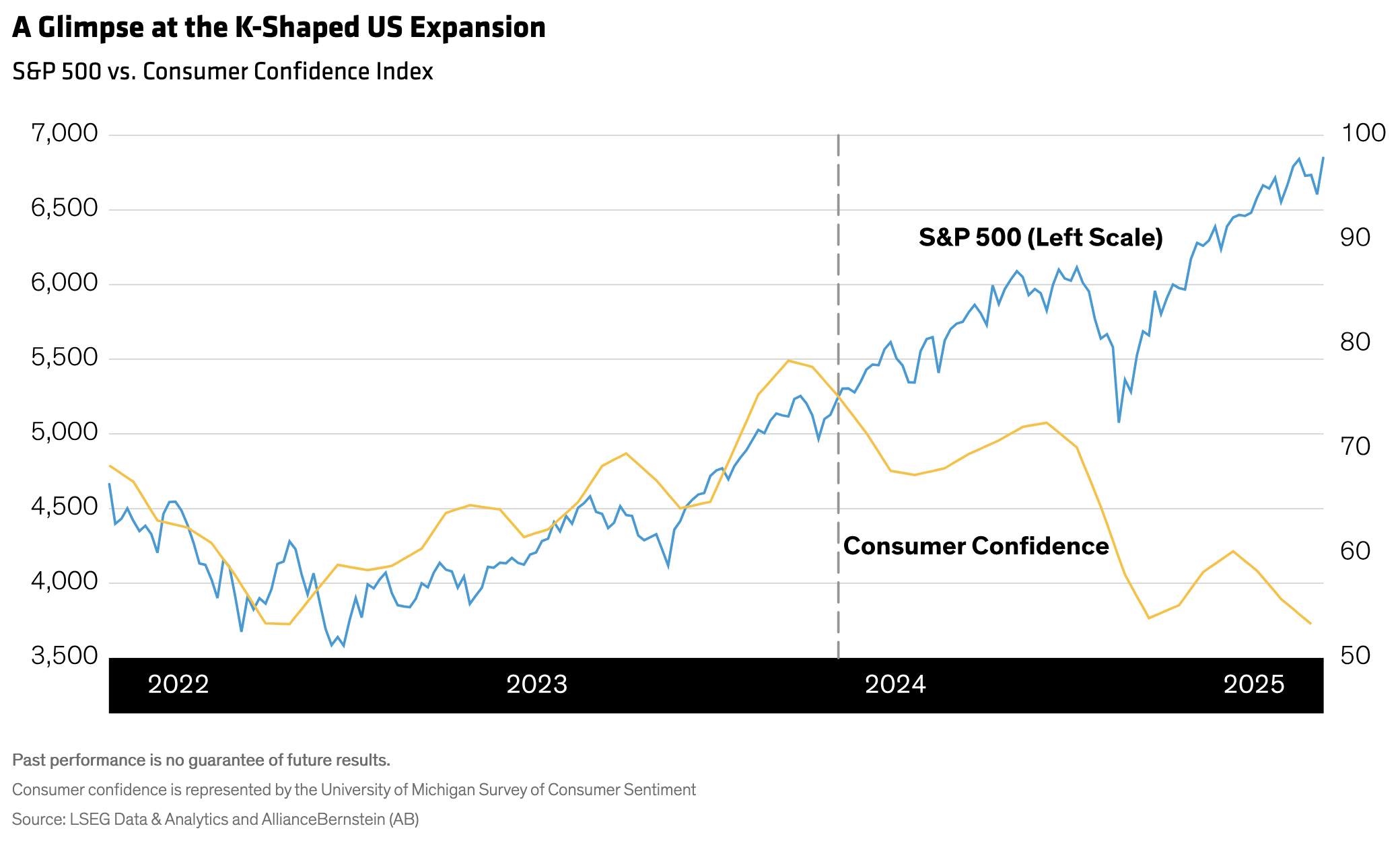

While our base case outlook is relatively benign, a look below the surface reveals frictions. The US expansion is increasingly supported by a combination of AI-related tech investments and consumption by society’s top earners. That makes the growth narrow, not broad, and it could mean vulnerability to specific shocks in a way that a broader expansion might be better able to weather.

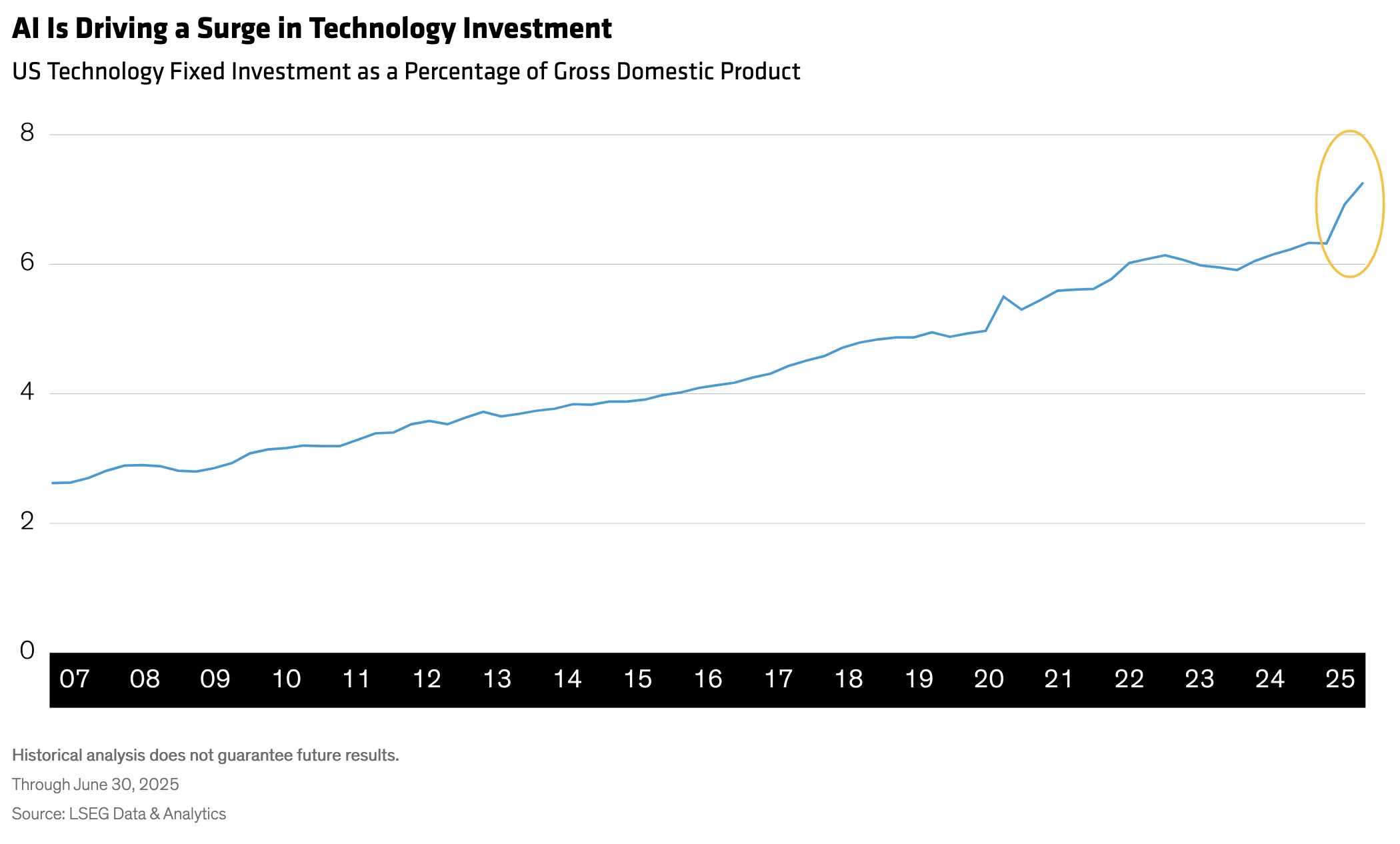

It’s not news at this point that AI has the potential to revolutionize the economy, and businesses have taken notice, digging deep into their wallets. After years of rising steadily, fixed investment in technology has surged over the past year (Display); today, it’s now more than 7% of gross domestic product (GDP). We expect that capital deployment to continue in 2026, though pressure will gradually mount on the companies most heavily invested in AI to show economic results.

If those results don’t appear quickly enough to satisfy markets, we could see a correction. In and of itself, a market sell-off isn’t an economic problem, but consumption is very concentrated among the wealthy right now, so the hit could be sharper. If financial assets lose substantial value, a “negative wealth effect” could cause knock-on effects from a market fluctuation to the real economy. In other words, declining financial wealth could cool spending and consumption among this cohort.

Moderate US Economic Expansion, but K-Shaped

Moderate US Economic Expansion, but K-Shaped

While that situation bears watching, for now we expect investment to be a net positive for growth in 2026, especially in the second half of the year as businesses become more accustomed to the tariff regime introduced in 2025. As uncertainty diminishes, we anticipate that activity will pick up, leading us to forecast US GDP growth of 1.75% next year, roughly the economy’s long-term potential rate. But that growth won’t be distributed evenly.

Surging tech investment has come at the expense of the labor market; businesses have been more willing to “hire” AI than workers, producing a “K” shaped expansion (Display). The finances of the wealthy are improving alongside financial assets, which benefit from corporate profits—the upward leg of the “K.” Those not invested in financial assets or whose income doesn’t track profits are the downward leg, struggling as the labor market softens. The top 10% of income earners are now roughly 50% of total consumption, a share we expect to rise as technology boosts returns on capital versus labor.

Deepening use of technology may widen inequality, but it should also help bring inflation back down toward the Federal Reserve’s target over time—supporting more rate cuts in 2026. We currently forecast that the Fed will bring rates down to 2.50% to 2.75% in the next few quarters, somewhat below market expectations. From a medium-term perspective, the central bank still has ample room to cut rates if our benign economic outlook proves incorrect. If conditions worsen, the Fed can cut more, supporting the real economy and boosting financial markets.

China Shifts Trade Flows, with Domestic Consumption a Challenge

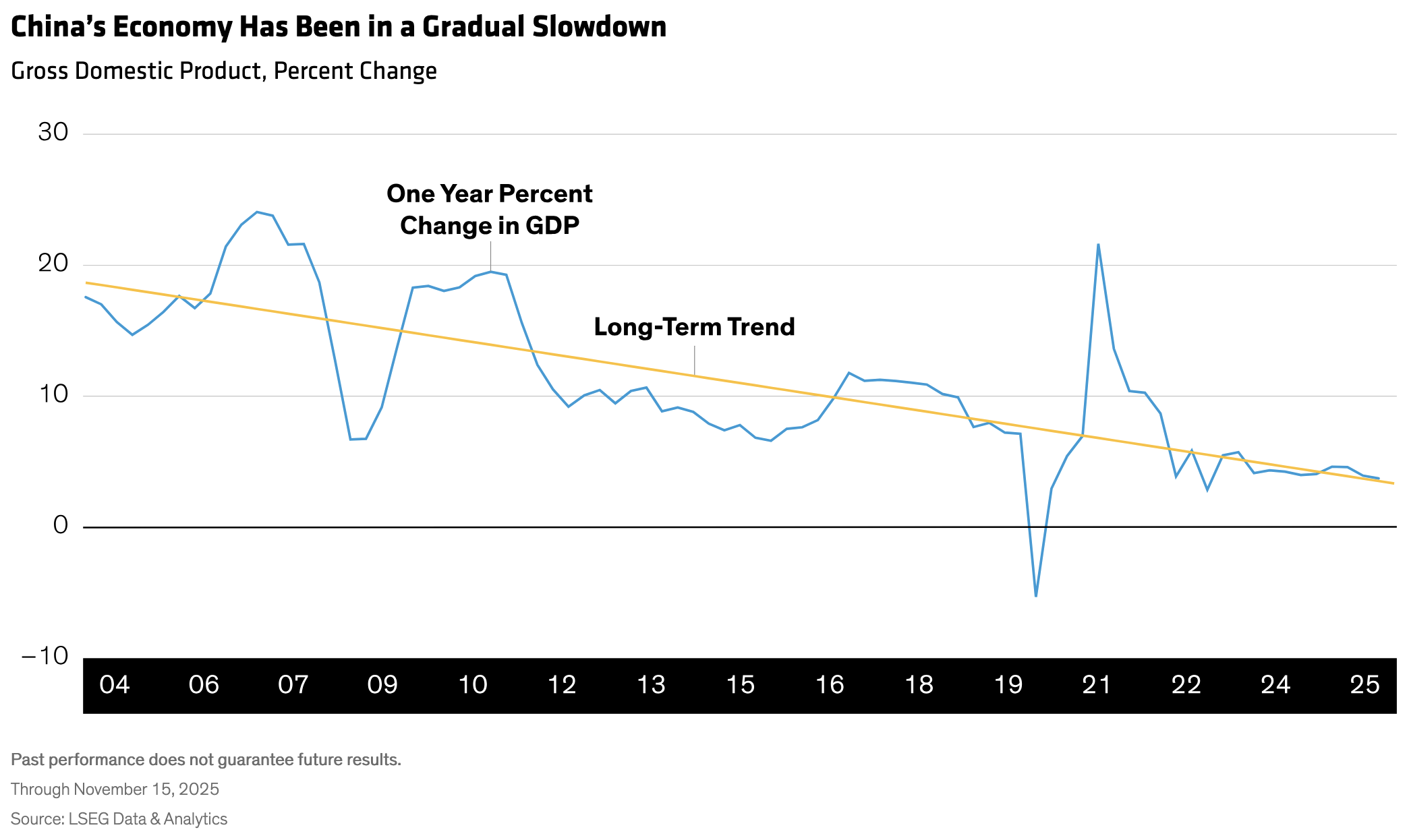

Outside the US, the adjustment to the new tariff regime was the front-page story of 2025 and will likely continue into 2026. China is still in a gradual economic slowdown (Display) as its society ages, and policymakers faced the added challenge of trade restrictions in 2025. They maintained the growth trajectory largely by redirecting exports away from the US to other Asian countries, as well as South America and Europe.

That realignment of trade flows will probably persist in the years ahead, barring a sudden thaw in relations between China and the US. But the Chinese economy faces a bigger challenge—weak domestic demand. Barring a dramatic fiscal stimulus package, it’s hard to envision that headwind shifting in 2026. Sluggish domestic consumption will likely keep prices low, so China seems in greater danger of deflation than of inflation running too hot.

Europe’s Growth Is Holding on, but Inflation Cooling Will Continue

Despite the threat of tariffs, growth in Europe was more resilient than expected, but zooming into the details reveals weaknesses. Ireland and Spain have outperformed the rest of the region, but elsewhere the eurozone is barely growing. The outlook is modestly brighter, with Germany planning substantial fiscal stimulus and some countries on the periphery expected to remain stronger.

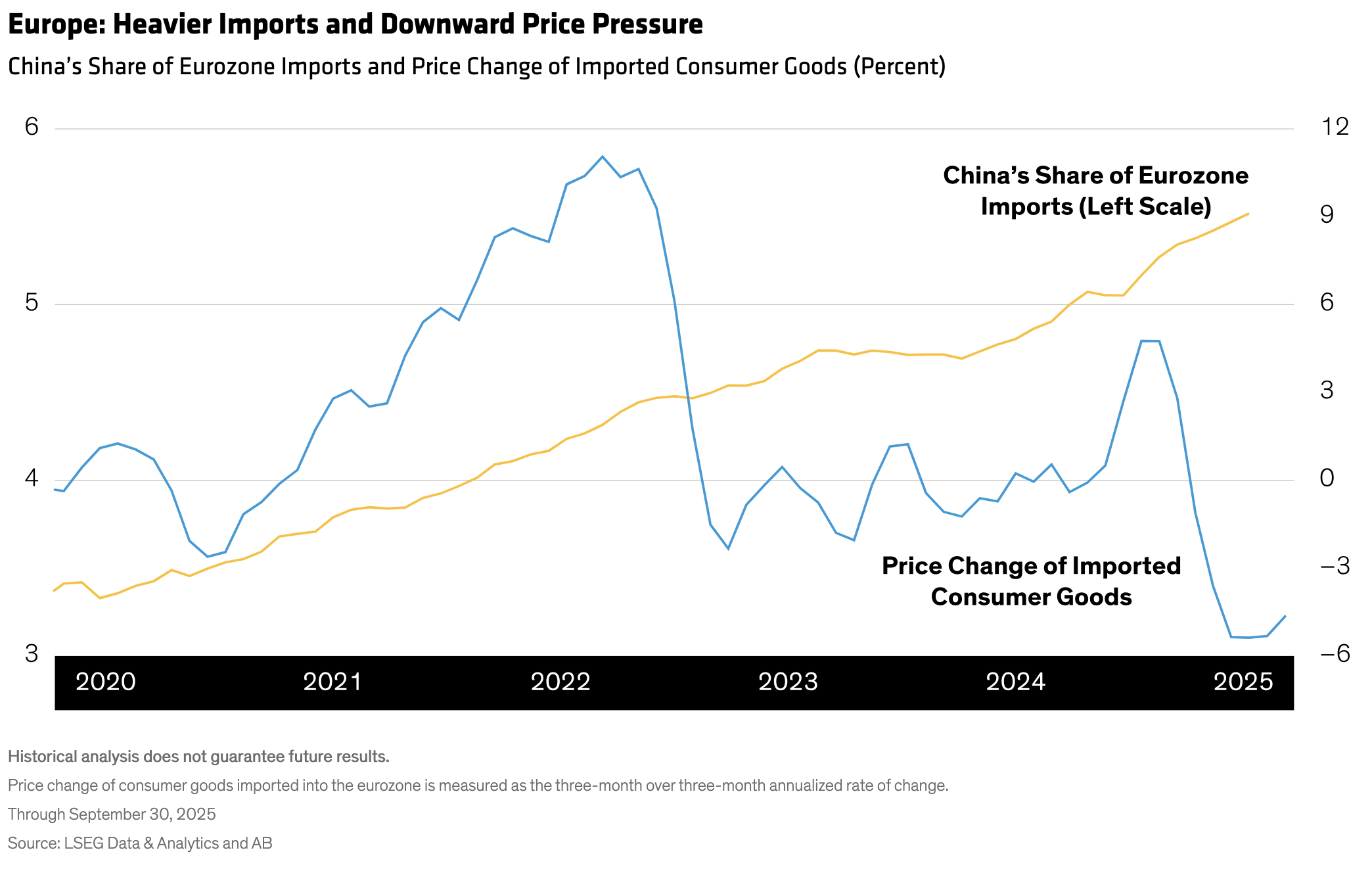

But private demand remains weak, and economies are exposed to external shocks and structural global changes. Shifts in global trade flows away from the US and into Europe stiffens competition with domestic firms and puts downward pressure on inflation (Display). While headline inflation is sustainably on target now, it’s likely to consistently undershoot targets over the medium-term. The drivers extend beyond trade flows: easing in domestic services prices, a stronger euro and low energy prices will matter, too. The European Central Bank seems comfortable with current interest rates, but we see one more cut in 2026, with risks still tilted to the downside with potentially more reductions.

The Economy Should Stay on Track—but Expect Surprises

As always, our most confident forecast is that the unexpected will happen in 2026—and there’s already a list of candidates. It could be the identity of the next Fed Chair or the possibility that the Supreme Court moves the Fed under the executive branch’s purview. Geopolitical developments always lurk, and something entirely off-radar could emerge. The world is too complicated a place for any outlook to capture everything that will unfold.

Still, we take comfort from the resilience that the global economy demonstrated in 2025, withstanding a variety of policy changes and other developments that could have knocked it off course. That fortitude is the most important trend that we expect to continue in 2026. While the unexpected could always occur, at least as of now we believe the global economy will remain on track next year.

About the Authors

Eric Winograd is a Senior Vice President and Director of Developed Market Economic Research. He joined the firm in 2017. From 2010 to 2016, Winograd was the senior economist at MKP Capital Management, a US-based diversified alternatives manager. From 2008 to 2010, he was the senior macro strategist at HSBC North America. Earlier in his career, Winograd worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the World Bank. He holds a BA (cum laude) in Asian studies from Dartmouth College and an MA in international studies from the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. Location: New York

Sandra Rhouma is a Vice President and European economist on the Fixed Income team. Previously, she was a global economist and strategist at Millennium Global Investments, a London-based currency investment manager. From 2019 to 2022, Rhouma worked for the European Central Bank as a banking supervision analyst before moving into a US economist position. She holds a PhD in economics from the University of Surrey and a master’s degree from Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Location: London

Eric Liu is a Senior Vice President and Portfolio Manager on the Asia Fixed Income team, focusing on offshore and onshore China, Asia Pacific, and emerging-market fixed-income strategies. Prior to joining AB in 2023, he was head of fixed income and portfolio manager at Harvest Global Investments, responsible for renminbi, Hong Kong–dollar and US-dollar fixed-income strategies. Prior to that, Liu held various fixed-income portfolio management and trading positions at Manulife Investment Management, Citigroup and Standard Chartered. He holds a MSc in investment management from The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and a BSc (Hons) in computer and management science from the University of Warwick. Location: Hong Kong