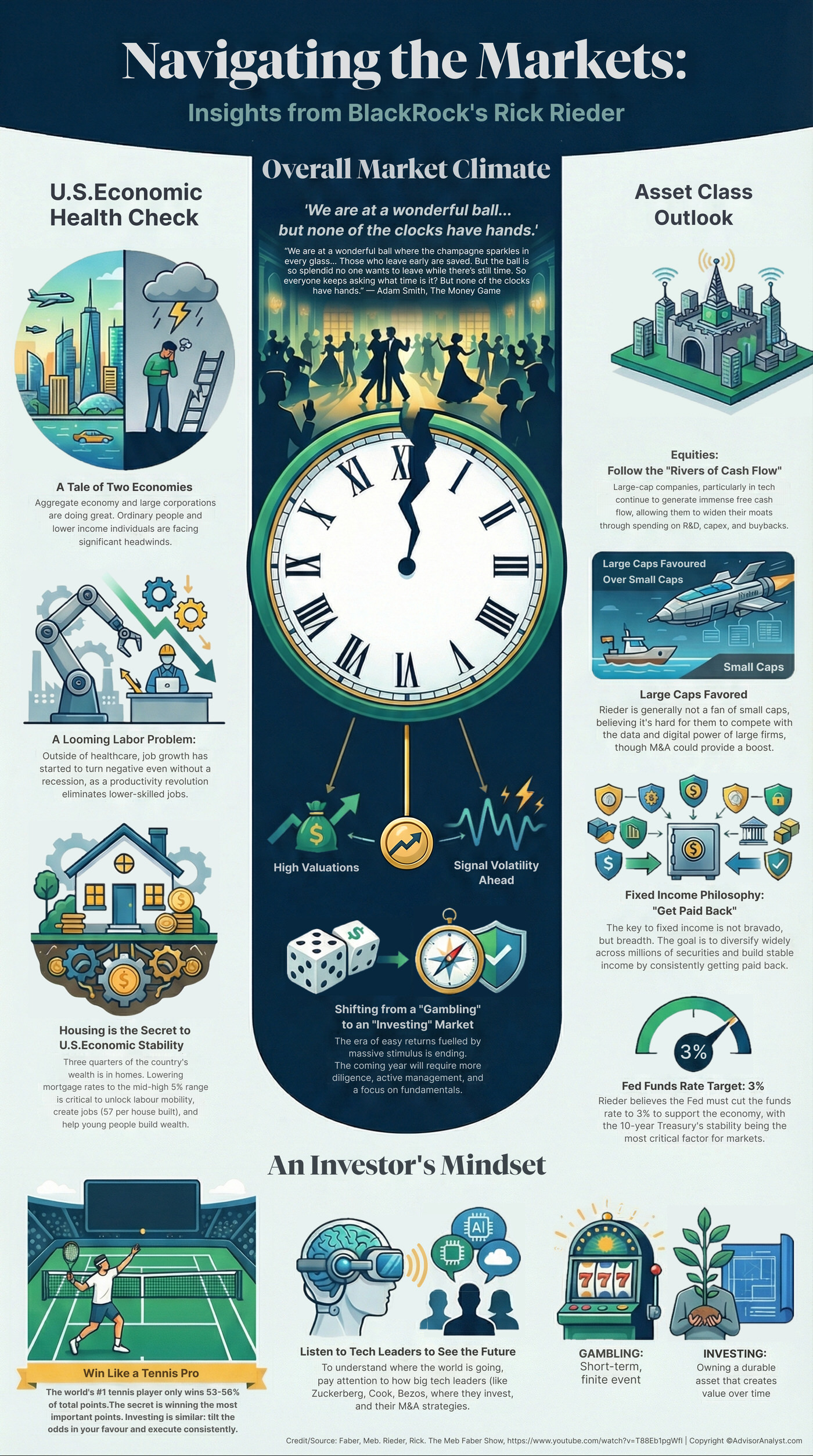

As markets drift toward year-end with equities at all-time highs and investors feeling “fat and happy,” Meb Faber opens the conversation1 with an image borrowed from Adam Smith’s The Money Game: a glittering ballroom, champagne flowing freely, and no hands visible on the clocks to tell investors when the party ends.

“We are at a wonderful ball where the champagne sparkles in every glass… Those who leave early are saved. But the ball is so splendid no one wants to leave while there’s still time. So everyone keeps asking what time is it? But none of the clocks have hands.”

Rick Rieder, Chief Investment Officer of Global Fixed Income at BlackRock, doesn’t dispute the metaphor. In fact, he leans into it. The markets, he says, feel exactly like that moment where everything appears fine on the surface—yet liquidity is thinner, volatility is lurking, and underlying dynamics are shifting.

“It is incredible how the markets do that… There shouldn’t be a difference between this month and next, but there is,” Rieder notes, describing how year-end liquidity fades, aberrational moves appear, and investors become more focused on protecting gains than deploying capital .

November, he adds, “felt worse than it ended up being,” a reminder that volatility can be emotionally violent even when markets finish in the black.

Rivers of Cash and the Equity Market’s Two Realities

Faber presses Rieder on one of his most memorable phrases: the idea that today’s largest companies are generating “fast rivers of cash flow.” Rieder doesn’t hesitate.

“I’ve never seen anything like it at this scale,” he says. “Top line revenue growth, return on equity, and free cash flow of this size—it’s extraordinary.”

Free cash flow, Rieder emphasizes, is not just a metric—it’s a self-reinforcing moat. Companies that generate it at scale can reinvest aggressively, fund R&D, buy back shares, and extend competitive advantages almost indefinitely.

“When you’re performing at that level… you’re extending your moat. You’re building it.”

That cash-flow reality underpins his continued confidence in large-cap equities, even as valuations remain elevated. High multiples, he cautions, are not reliable predictors of near-term market direction—but they are predictors of volatility.

“Whenever multiples are higher… it doesn’t necessarily mean markets go down. But it does tell you that volatility will be higher.”

The more difficult question lies outside the top 20–25 stocks.

“You get through it with those big companies,” Rieder says. “But the other 475? That’s harder.”

A More Normal Market—and a Tougher One

Looking ahead, Rieder expects a different regime—not a bearish one, but a more selective and volatile one.

“I think it’ll be a more normalized return dynamic,” he explains.

Small caps, long trapped in the penalty box, may finally see differentiation—not because conditions suddenly favour them, but because mergers, acquisitions, and AI-enabled efficiency will separate survivors from laggards.

“I don’t like small caps very often,” Rieder admits. “Digital and data utilization make it very hard to compete.” Still, AI may “democratize business” in ways that allow some smaller firms to pivot successfully.

Sector-wise, his preferences remain clear:

- Technology remains dominant

- Healthcare technology is “super interesting”

- Financials remain “in pretty good shape”

Traditional value stocks, by contrast, still don’t earn a central role.

“I don’t love them as the core of the portfolio,” he says, “but I think you have to give them a little bit of time.”

Strong Companies, Strained Workers

One of the most important—and least celebrated—themes of the discussion emerges when Faber highlights a troubling data point: job growth turning negative outside of healthcare, something historically associated with recessions.

Rieder doesn’t minimize it.

“I think companies are doing great in aggregate because they’re cutting costs. I think people—not so much.”

What’s unfolding, he argues, is a productivity revolution—driven not just by AI, but by logistics optimization, inventory management, predictive maintenance, and data-driven procurement.

“All the ordinary jobs… the lower-skilled jobs are going away. And I think it’s a travesty.”

This dynamic creates a paradox: consumption remains resilient due to accumulated wealth among higher-income and older cohorts, while employment opportunities for others shrink.

“That’s going to be the story of the next two or three years,” Rieder warns. “We have a hard time employing the number of people that we should.”

Tariffs, Housing, and the Real Economy

On tariffs, Rieder pushes back against recession hysteria.

“The U.S. economy has the highest amount of imports in the world—and is also the least reliant on trade.”

While tariffs can push inflation higher in the short term, he expects productivity gains to offset them over time. More importantly, tariffs are becoming a fiscal tool.

“They could make up three to three and a half trillion dollars of deficit over the next ten years.”

Housing, however, is the real pressure point.

“Three-quarters of the wealth in this country is in people’s homes.”

Without housing velocity, labor mobility suffers, construction employment stalls, and wealth formation for younger households breaks down. Lower mortgage rates are essential.

“If we can get mortgage rates into the mid to high fives, you start to see housing velocity pick up.”

Rates: The Fed Funds Rate Is a Distraction

Rieder is unusually direct about where rates need to go.

“I think we’ve got to get the Fed funds rate to 3%.”

Markets have largely priced it in—but he believes it should happen faster, both to ease fiscal pressure and to stabilize the economy. Longer-term, he expects the terminal rate to be even lower due to technology-driven disinflation.

Yet the real focal point isn’t the Fed funds rate at all.

“Nobody borrows off the Fed funds rate,” Rieder says flatly. “The most important thing for monetary policy is the 10-year Treasury.”

Stability in the 10-year—between 3.5% and 4%—would anchor mortgages, debt servicing, currencies, and investor confidence.

Fixed Income: Breadth Over Bravado

Perhaps the most philosophically revealing moment comes when Faber asks Rieder to expand on a quote about fixed income being about “getting paid back over and over again.”

“This took me 40 years to figure out,” Rieder says. “In fixed income, the whole game is just ‘get paid back.’”

Unlike equities, there is no convex upside. Success comes from diversification, repetition, and probability—not hero trades.

“Go broad. Diversify. Do it a billion times.”

He compares the approach to running a casino: tilt the odds slightly in your favor, apply discipline, and let compounding do the rest.

Equities, by contrast, reward concentration and growth. That distinction explains why Rieder is skeptical of long-duration Treasuries as an asset allocation substitute for stocks.

Where the Landmines Are—and Aren’t

Asked where risks may be hiding, Rieder doesn’t sugarcoat the outlook for 2026.

“I think 2026 is going to be more alpha, less beta.”

Credit quality is beginning to deteriorate in pockets—subprime auto, certain middle-market software loans, and underwritten private credit deals. Defaults are likely to rise.

“That’s not a systemic risk,” he says, “but there will be more landmines.”

The response? Diversification, diligence, and income—not speculation.

“We’re moving from gambling to investing.”

Gambling vs. Investing: The Nadal Lesson

Rieder illustrates his philosophy with an unexpected sports analogy. Rafael Nadal won 97% of his matches at the French Opens—but only about 55% of points.

“He won the important points.”

The world's #1 tennis player only wins 53-56% of total points. The secret is winning the most important points. Investing is similar: tilt the odds in your favour and execute consistently.

Investing, Rieder argues, works the same way. You don’t need to be right all the time. You need to be right often enough, in the right places, with the odds on your side.

“If you tilt the odds in your favor… and do it a billion times, that’s the whole gig.”

Gold, Technology, and Watching the Crowd

On gold, Rieder attributes recent strength less to inflation fears and more to global reserve diversification.

“Central banks are saying, ‘I’ve held dollars for a long time. I need to diversify.’”

Technicals, he adds, often overpower fundamentals—especially in the short and intermediate term.

That same lens shapes his view of technology adoption. Whether it’s autonomous driving, smart glasses, or satellite internet, Rieder believes investors must use new tools to understand them.

“You’ve got to be the first in line to try these things.”

But the implications are sobering.

“There are four million people in the U.S. employed in driving… This is happening so fast.”

Retraining the Brain for 2026

As the conversation closes, Rieder leaves listeners with a warning—and a dose of optimism.

“We’ve got to retrain our brain.”

The easy trend-following years are fading. Volatility will rise. Dispersion will increase. Tools must evolve.

“I’m more pumped up for 26 than I’ve ever been,” he says. “It’s not bad. It’s just different.”

The champagne may still be flowing. But for those listening closely, the clocks’ hands—while still invisible—are beginning to tick.

Footnotes:

1 Show, The Meb Faber. "BlackRock's Rick Rieder: Warning Signs Are Flashing." YouTube, 12 Dec. 2025.

Copyright © AdvisorAnalyst.com