In the third part of his return expectations series1, AQR’s Principal and Global Co-Head of Portfolio Solutions Group, Antti Ilmanen dives into a question that seems obvious—but surprisingly, isn’t well-covered in the academic world: Why do bond investors often bet on reversals, while equity investors tend to chase trends? His take is clear: it comes down to what catches our attention—or as he puts it, information salience.

Let’s unpack what that really means—and why understanding this behavioral split could be key to managing portfolio expectations in today’s uncertain environment.

Bonds: The Contrarian’s Playground

Here’s Ilmanen’s headline observation: “Bond investors tend to expect reversals and stock investors continuations.” That means when bond yields plunge, bond investors don’t get euphoric—they brace for a rebound. Equity investors? When markets fly, they double down.

Why the difference? Ilmanen explains it this way: “Bond investors are used to thinking about market yields which are inherently forward-looking,” while equity investors fixate on past prices and returns. So while the bond world talks about yields (a future-facing number), the equity world gets swept up in prices and recent momentum. It’s a subtle but powerful shift in framing.

The Great Rate Forecasting Fail

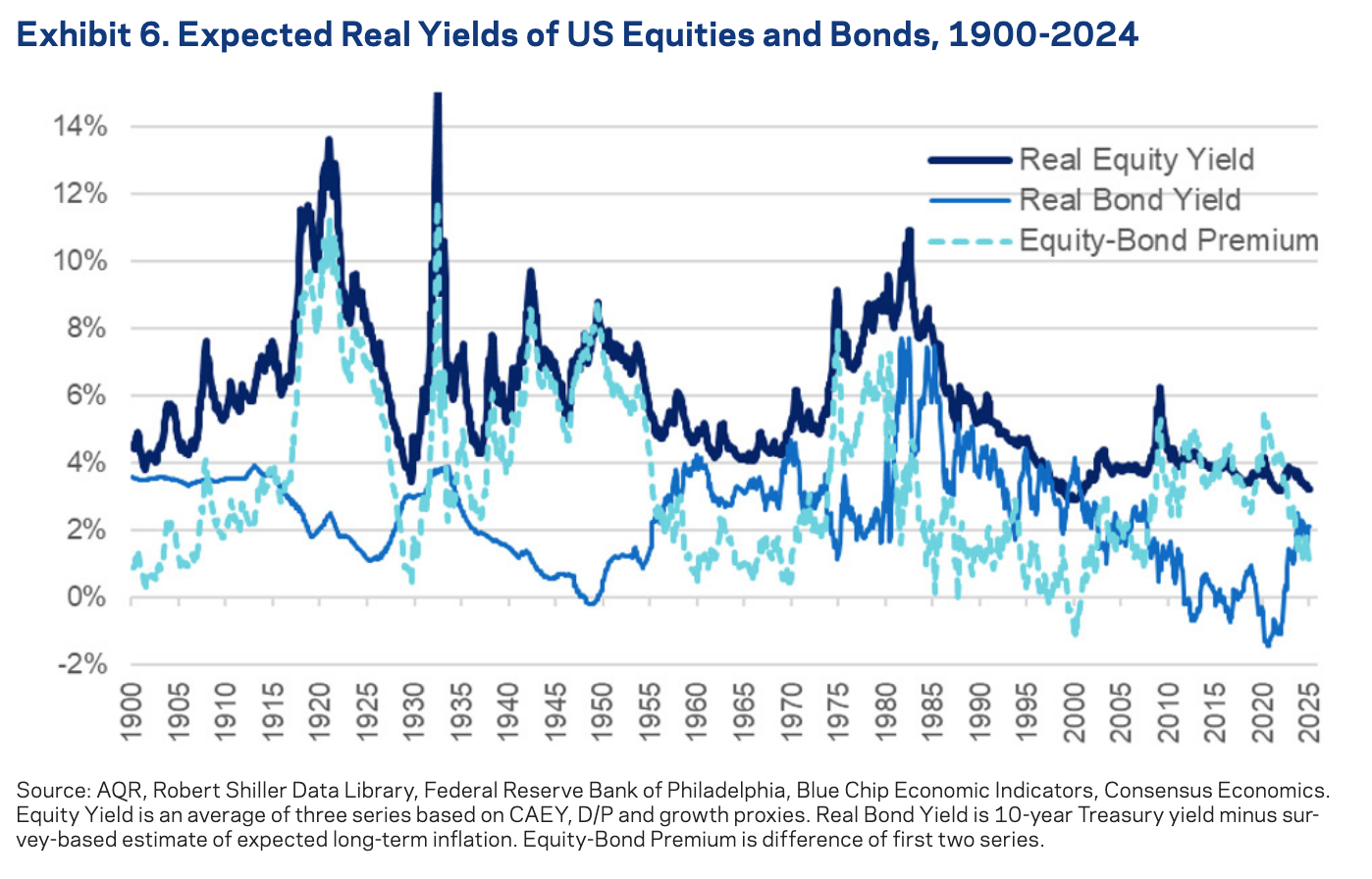

Ilmanen pulls up Exhibit 1—decades of forecasts showing experts confidently predicting rising rates that... didn’t happen. “Consensus expectations toward rising rates turned out to be wrong, wrong, wrong for a long time,” he writes. But he’s sympathetic. Economists were acting on what seemed like rational assumptions—expecting yields to normalize toward historical averages. They just didn’t anticipate a 40-year structural downtrend in real rates.

Even the market got it wrong. So while forecasters took the heat, “all-knowing” forward rates didn’t do any better. The takeaway? Bond markets are steeped in mean reversion—even when reality repeatedly says otherwise.

Stocks: The Eternal Optimists

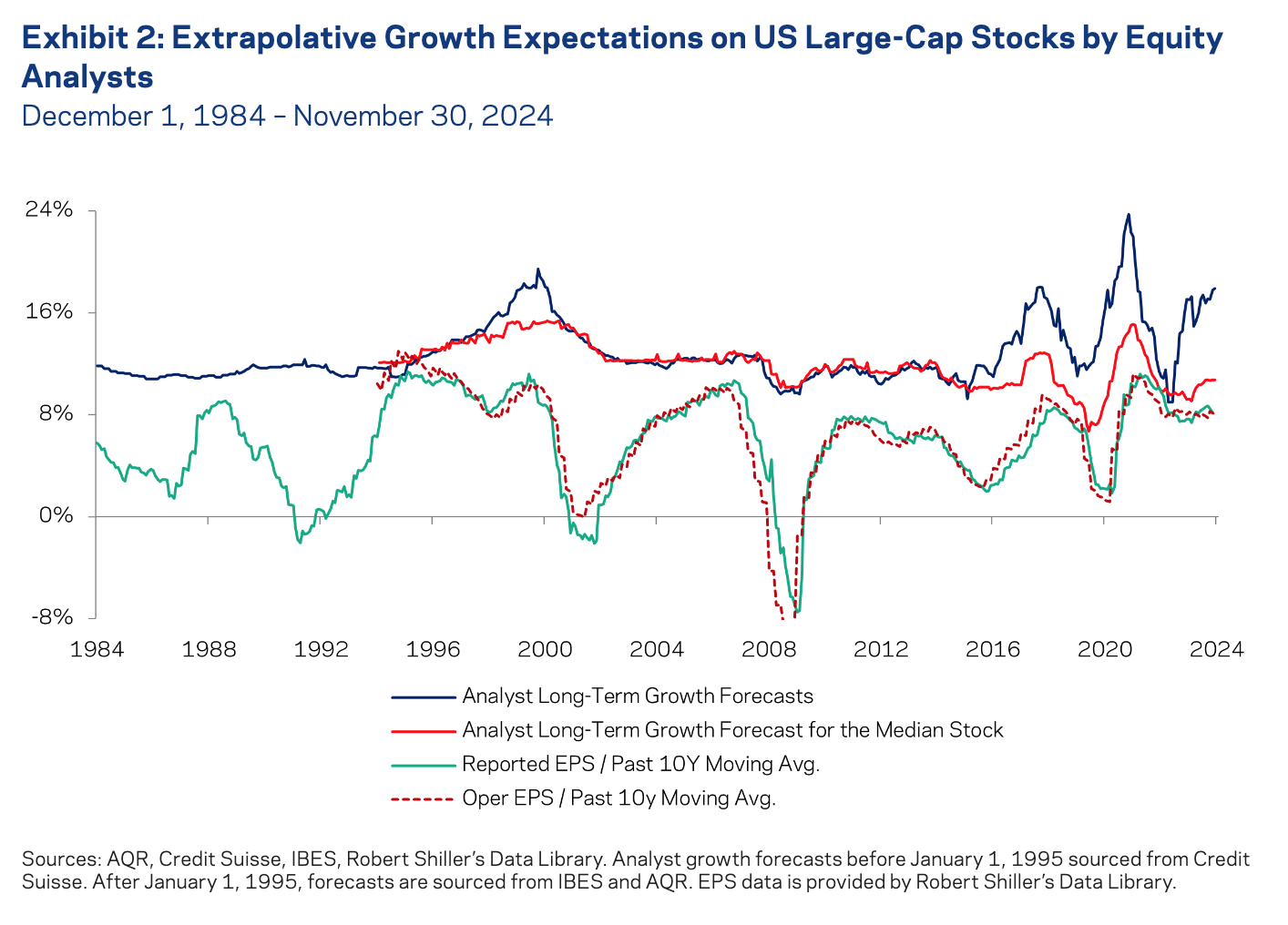

Flip the script to equities, and the mood is completely different. Exhibit 2 shows how equity analysts have spent the past 40 years consistently overshooting on long-term earnings growth. How much? On average, they expected more than double what actually materialized.

And it’s not just excessive—it’s cyclical. “Analyst forecasts… are extrapolative—and thus quite poor market-timers,” Ilmanen points out. Their optimism peaked in 2000, 2021, and again in 2025—each just before markets rolled over.

Tech giants have been the biggest beneficiaries of this rose-colored forecasting. When expectations for mega-cap names surged ahead of the median stock—like in 1999 or today—it signaled extreme dispersion and growing risk.

Home Bias and Global Myopia

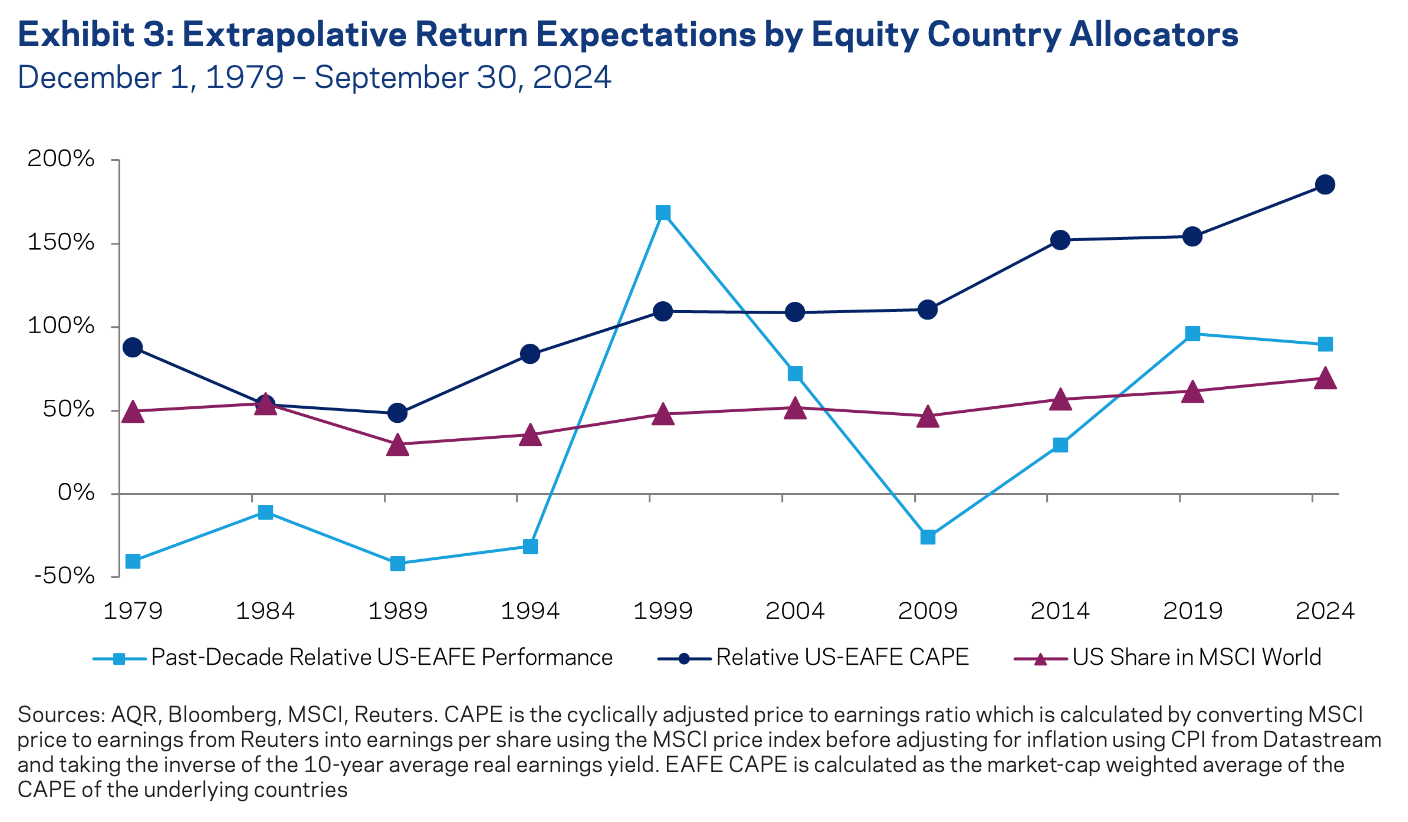

In Exhibit 3, Ilmanen shows how investors have shifted capital toward U.S. equities after strong periods of performance, and away after weak ones. That might seem rational—until you realize that U.S. stocks are now trading at nearly double the valuation of their international peers.

So why does everyone keep piling in? Simple: they’re extrapolating. “We can only make sense of these allocation choices if investors assign a record-high prospective growth advantage for the U.S.… guided by an extrapolative mindset,” he writes.

Why the Disconnect?

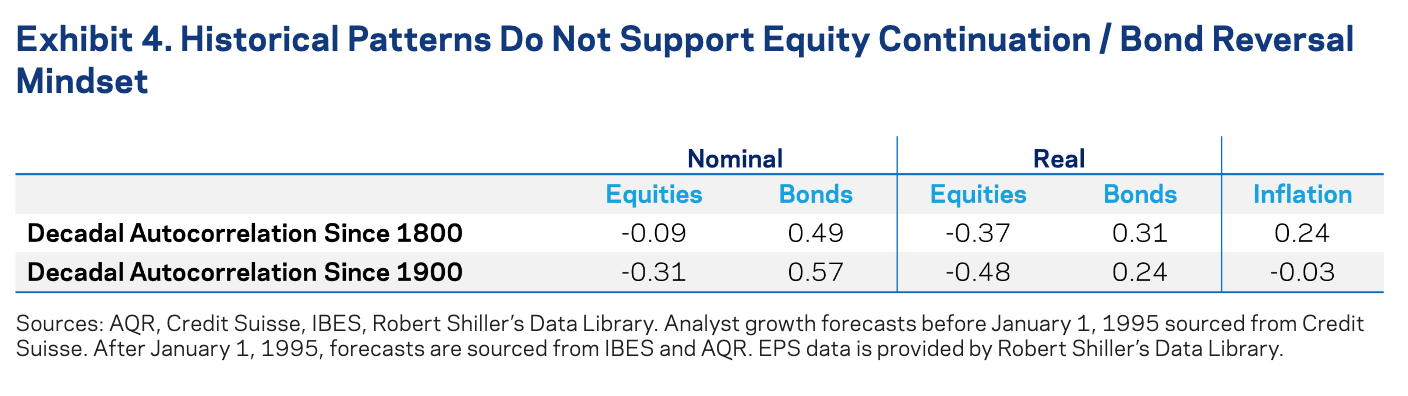

If historical data shows bond returns are actually positively autocorrelated (they trend) and equities mildly mean-revert, why are investors behaving the opposite way?

Ilmanen points to information salience. “Bond yields are easy to access and understand,” he notes. “Equity yields… require academic models.” The story investors see—yields versus prices—shapes how they form expectations. And most folks remember the big moves, not the valuation signals.

History Has a Message

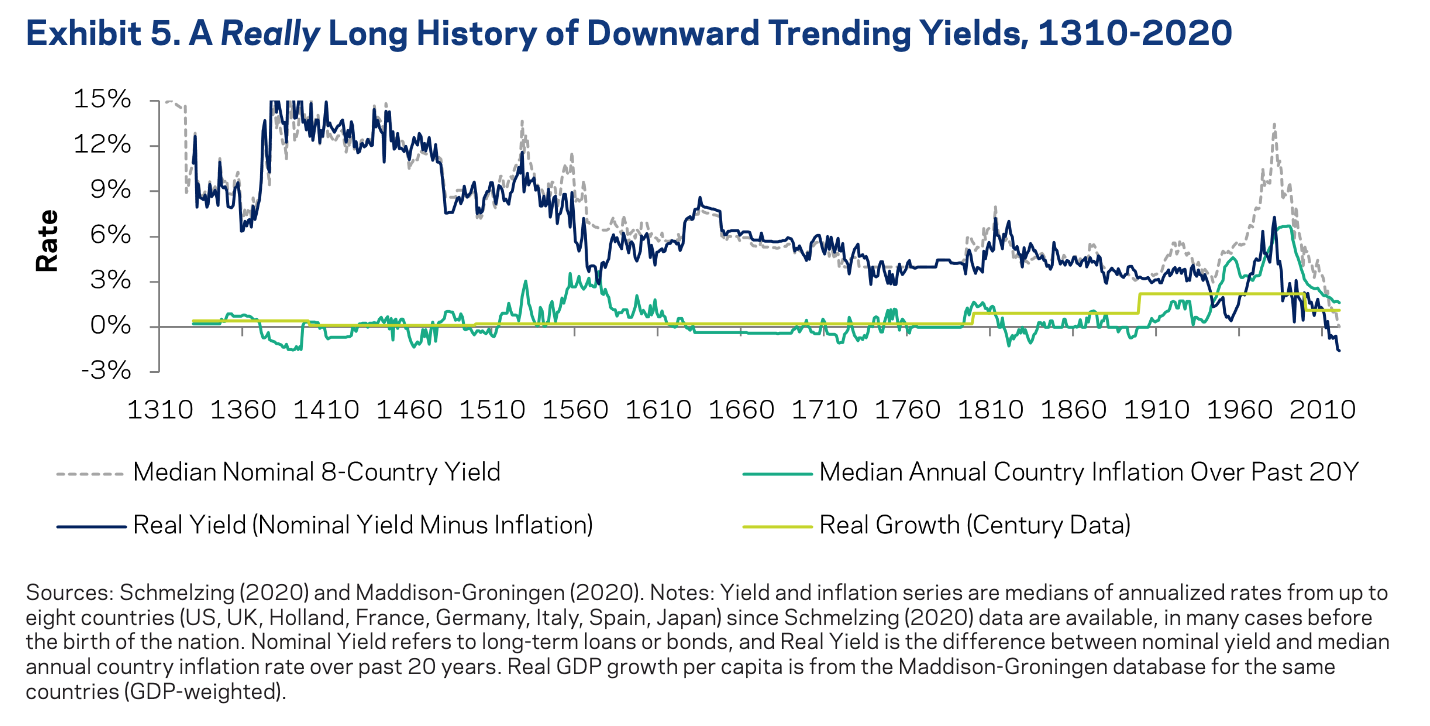

Exhibit 5 shows a centuries-long drop in real yields—from the double digits in the Middle Ages to negative territory in the 2010s. Ilmanen believes we may have hit bottom: “Most observers believe that the secular downtrend… is over. So do I.”

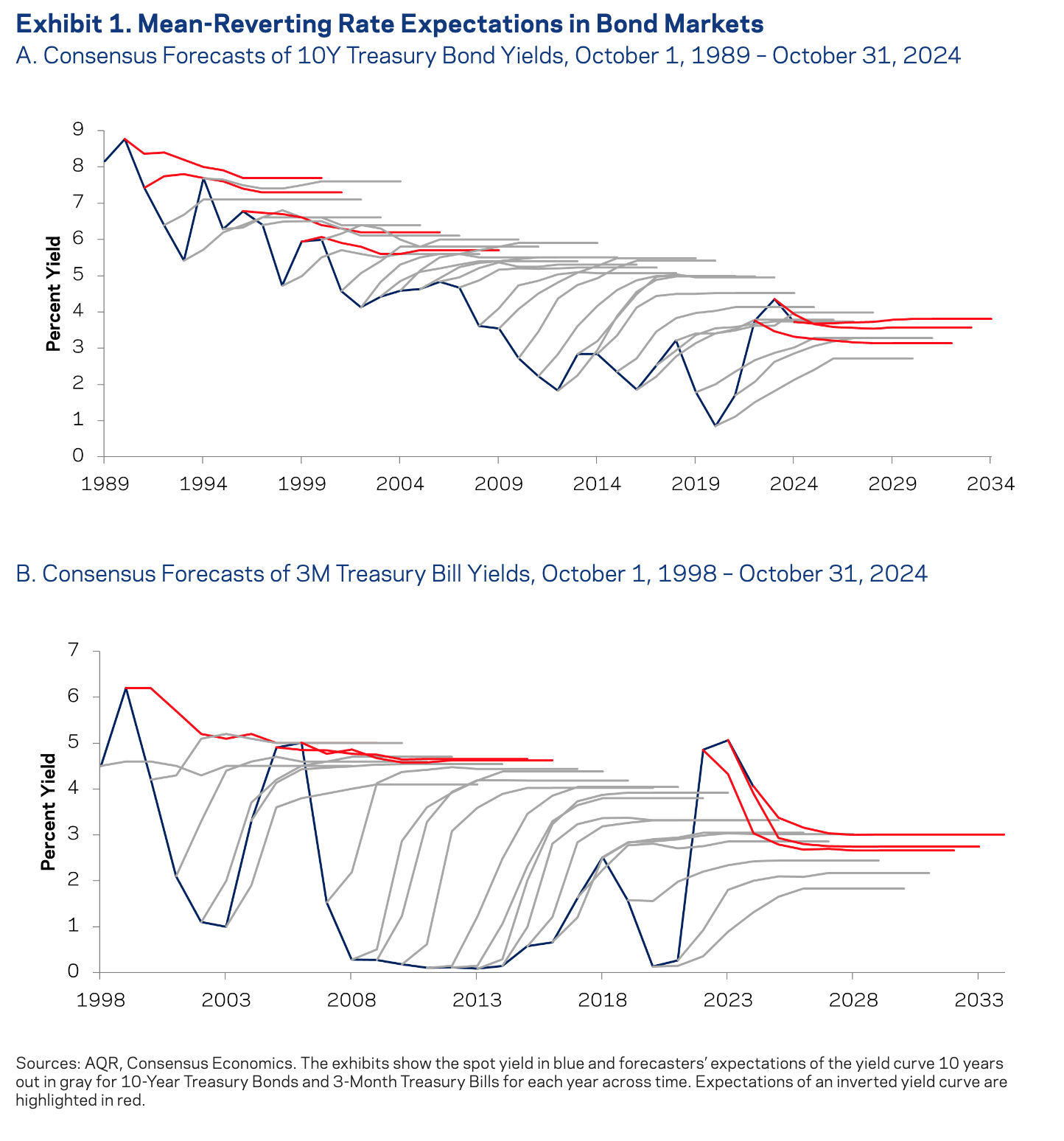

Exhibit 6 adds another warning: the once-comforting equity risk premium is shrinking. In the 1999 bubble, it even went negative. Today, that premium is again razor-thin, implying future returns might disappoint—especially if you’re looking through a rearview mirror.

Beware the Rearview Mirror

Ilmanen ends with a reality check—five reasons why anchoring to past returns is risky:

- Equity returns over the past 30–40 years were artificially boosted by falling rates and tax cuts.

- Growth wasn’t productivity-driven—it was debt-fueled.

- That debt? It’s still here, now colliding with demographics, defense, decarbonization, and instability.

- Valuations remain high—especially in risky assets.

- Too many investors are counting on private markets to deliver magical returns. Spoiler: they might not.

“Easy to sound like Cassandra here,” he quips. “I asked ChatGPT if AI would come to the rescue. It wasn’t sure.”

What This Means for You

Ilmanen isn’t pushing a specific forecast—he’s pushing for realism. Recognize your own biases. Pay attention to what information is shaping your expectations. Because as he gently reminds us, just because stocks soared last decade doesn’t mean they will again.

Contrarian thinking isn’t always right. But blind optimism? That’s usually wrong eventually.

Footnote:

1 Antti Illmanen, AQR. "Why Are Bond Investors Contrarian While Equity Investors Extrapolate?" May, 2025

Copyright © AdvisorAnalyst