by Owen A. Lamont, Ph.D., Senior Vice President, Portfolio Manager, Research, Acadian Asset Management

There is no such thing as “the U.S. stock market.” Today, we have two U.S. stock markets: big growth stocks and everything else. At least, that’s the conclusion that comes from studying daily return correlations. Big growth is increasingly disconnected from the rest of the market, and the current disconnect is at the 99th percentile relative to U.S. history since 1926. It’s as if big growth trades on a different stock market than everything else (such as value and small cap).

In recent decades, global stock markets have integrated, and consequently stock returns in different countries have become more correlated. For example, the daily correlation of U.S. stock markets with global ex-U.S. has doubled from around 40% in the 1990s to around 80% today. But while the rest of the world has integrated with the U.S., the U.S. market itself has dis-integrated in the past five years. The correlation of big growth stocks with everything else has fallen from around 90% historically to the current level of 60% or lower. Big growth stocks (such as Tesla) as a group no longer move in sync with everything else (such as Ford).[1]

Should we be alarmed by today’s bifurcation? I’m not sure. Let me give two opposing interpretations:

- Bifurcation is bad. Bifurcated markets are a symptom of speculative excess, with big growth stocks being pushed up by irrational optimists, while other stocks are neglected. The market is broken.

- Bifurcation is good. It’s not the stock market that has bifurcated, it’s the underlying firms. The market is rationally responding to different fundamentals for different types of firms. Bifurcation makes the market less volatile, not more volatile.

Both views may be partly true. Rather than flatly asserting that “the market is broken,” I’d say that “the market is broken into two pieces called growth and value, which are becoming less correlated.” Whether this bifurcation is good or bad is unclear.

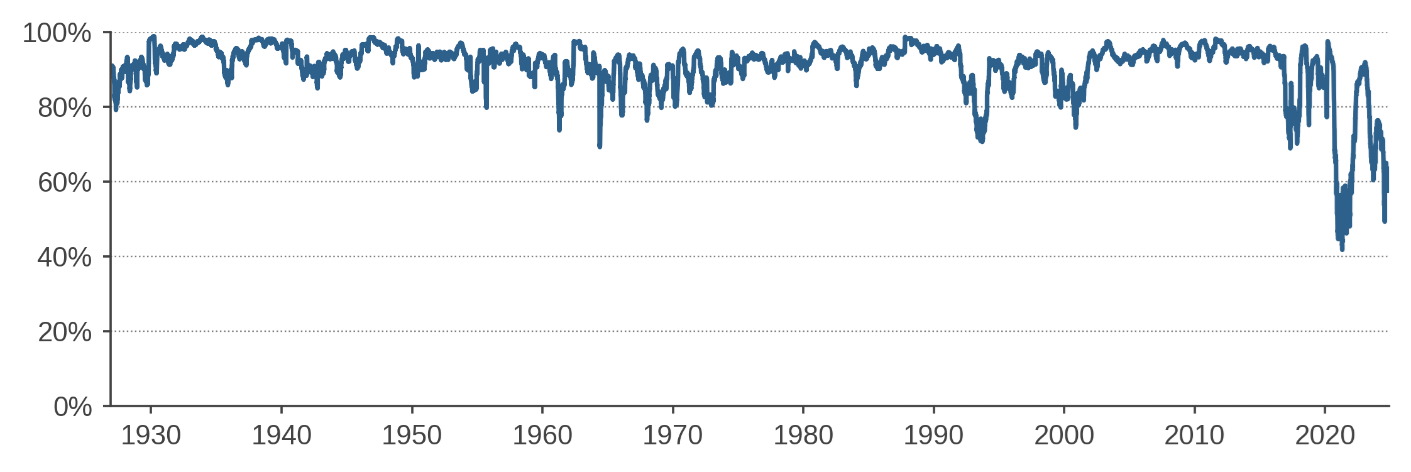

Breaking away: Return correlations, 1926-2024

Figure 1 shows rolling 120-day return correlations of big growth stocks with everything else since 1926, using data from Professor Ken French. I split the entire market into two groups: big growth (firms such as Tesla) and everything else (big value such as Ford, and all mid-cap and small-cap stocks).

For almost a century, from 1926 to 2019, big growth and everything else had a return correlation that was usually around 90% and almost never below 70%. Something changed in 2020. The 120-day trailing correlation plunged in 2021, reaching a low of 42% in April 2021. The correlation reverted to normal in 2023, then plunged again this year, reaching a low of 49% in July 2024. The most recent trailing correlation is 58% as of October 2024, which is lower than 99% of previous history.

Figure 1: Daily Correlation of Big Growth Stocks with the Rest of the U.S. Market

(rolling 120-day windows)

Source: Acadian based on data from the Kenneth R. French data library. Copyright 2024 Kenneth R. French. All Rights Reserved. For illustrative use only.

Figure 1’s dramatic decline in correlation can be replicated using different methodologies. First, you can use different portfolios. The daily return correlation of the Russell 1000 Growth vs. Russell 1000 Value indexes also fell from around 90% before 2020 to around 50% today (for more on these indexes, see Baker (2024)). Second, if you look at different frequencies, you see similar results. For example, rolling monthly return correlations are also unusually low today.

Figure 1 uses book/market as the only measure of valuation. If you think that book value is an increasingly irrelevant variable, then Figure 1 is all the more striking, since sorting stocks on meaningless noise would not be expected to produce changing covariation over time.

The correlations in Figure 1 are conceptually distinct from other commonly used measures of market dynamics. For example, consider the average pairwise correlation among stocks. This correlation reached record lows in July 2024, an interesting fact, but a separate fact than the correlation of big growth with everything else.[2] For example, if individual value stocks become more pairwise correlated with each other but less pairwise correlated with individual growth stocks, it’s possible that the average pairwise correlation would remain unchanged despite increased bifurcation. Similarly, measures of stock-specific dispersion (recently at record highs) are not designed to measure disconnect at a group level.[3]

Is the current bifurcation a sign that we are experiencing speculative excess today? Maybe, but if so, it’s unlike most previous bubbles. Figure 1 shows no huge bifurcation in the bubbles of 1929 or 1999; only the bubble of 2021 had noticeable bifurcation. So whatever is happening today, it’s not identical to the tech stock bubble of 1999.

Things fall apart: Other evidence for decoupling

A different measure of the disconnect between growth firms and other firms is the value spread, discussed for example in Acadian (2022) and Asness (2024). The value spread measures the cheapness of value stocks relative to growth stocks. It can be constructed in various different ways, but no matter how you define it, the spread has widened to extreme levels in recent years. Value looks exceptionally cheap relative to growth. Thus, the value spread is also telling us that value and growth have decoupled.

The value spread and daily return correlations measure different things. The value spread shows that levels of valuations relative to fundamentals have become disconnected. Return correlations show that daily changes in valuations have become disconnected. These two facts do not mechanically imply each other, and thus are independent pieces of evidence indicating that something about value/growth has changed.

Another way to understand the value/growth dynamic is to look at patterns in profitability. There is no doubt that there has been a fundamental shift in recent years for U.S. firms: big growth firms have become more profitable relative to other firms, as shown in Acadian (2019).

So, looking at these three measures of bifurcation—return correlations, value spreads, and profitability differences—it looks as if U.S. big growth firms are like an extreme version of the U.S. stock market: dynamic, profitable, and highly valued. The rest of the U.S. stock market resembles Europe: slower-growing firms with low valuations.

One coherent story, then, is that the fall in return correlations is due to fundamental bifurcation. That could be, but if so, I am left wondering what is driving the dramatic decline in correlations as of 2020. I would think that fundamental bifurcation is a slow-moving process, not something that suddenly happens in 2020. And the widening value spread and profit differences occurred prior to 2020, suggesting that the return correlation is somewhat unrelated to these variables.

A house divided: Explanations for bifurcation

I’ve already discussed changing fundamentals as an explanation for bifurcation. Here are some more guesses about the causes of bifurcation:

- Crazy retail traders using social media and trading apps. I’m unsure about this story, suggested by Asness (2024). I love studying idiotic meme stocks as much as the next behavioral economist, but I see retail traders as influencing the lunatic fringe of the stock market, not the cap-weighted aggregates.

- Flows into ETFs. Both individual and institutional investors are pumping dollars into ETFs corresponding to specific segments. Makes sense, but if so, why didn’t we also see huge bifurcation in 1999/2000 from the epic flows into growth mutual funds documented by Frazzini and Lamont (2005)?

- AI bubble. Crazy optimists are bidding up the prices of big-growth stocks. Could be, but again, how is this scenario different than 1999/2000, a market brimming with crazy optimists but not much bifurcation.

- The polarized market hypothesis. Big growth stocks are now seen as Republican-leaning and are traded by Republicans, while everything else is traded by Democrats. Unprecedented political bifurcation leads to unprecedented market bifurcation. An intriguing story that deserves further study.

And now some explanations that don’t fly:

- Indexing has caused the market to become increasingly top-down. False, at least if top-down means “moving in unison with the S&P 500.” The market has in fact become decreasingly top-down. While historically it is true that index inclusion caused increased covariation among index components (Barberis, Shleifer, and Wurgler (2005)), the bifurcation we currently see is the opposite of synchronous price moves.

- Interest rates. Interest rates have gone up and down a lot in the past hundred years. But suddenly today they generate bifurcation? I doubt it.

- Markets are distorted by concentration into the Magnificent Seven. No. As I have previously argued, market concentration was also high in the 1950s and 1960s, but Figure 1 shows no bifurcation then.

On this last point, I don’t deny that the Magnificent Seven are a major force in the stock market, but I think the underlying driving phenomenon is the behavior of big growth stocks as a (cap-weighted) group, and not the number of individual names or the concentration within that group.

When you use cap weights, concentration is irrelevant. If I were to take the Mag 7 and split each one into two clones, each identical to the original but with half the market cap, this newly defined Mag 14 would have exactly the same value-weighted returns as the original Mag 7. Nothing would change in Figure 1. Market concentration is a red herring.

So, yes, the Magnificent Seven firms dominate the big growth category and are in the forefront of fracturing the market. No, the fact that there are only seven of them is not especially important.

Across the great divide: Bifurcation vs. concentration

Should we be alarmed by market bifurcation? I’m not sure. Generally speaking, segmentation is a bad thing when it reflects impediments that prevent capital from flowing where it needs to go. I doubt that’s the case here.

Bifurcation has some benefits. For example, consider the oft-repeated claim that today’s market is excessively concentrated and therefore very risky. It’s just not true. As I’ve previously argued, you can’t just look at portfolio weights and intuit portfolio outcomes, because portfolio volatility is driven by return covariation. The truth is that aggregate market volatility in 2024 has been lower, not higher, partly due to market bifurcation.

Let’s do a thought experiment about market concentration using hypothetical numbers. Suppose we have a stock market where the Mag 7 is 10% of total market cap. Suppose the “everything else” portfolio has 15% volatility, while the Mag 7 portfolio has higher volatility of 25%. Further, suppose the return correlation of these two is 90%. Given these assumptions, total stock market volatility is 16% (you can find the math for this calculation in any finance textbook).

Now suppose we triple the market-cap weight on the Mag 7 from 10% to 30%, while also decreasing correlation with everything else from 90% to 50%. Is this more concentrated market, with higher weight in the more volatile Mag 7, riskier? Nope. In this scenario, market volatility goes down slightly, because decreased correlation outweighs increased concentration.

So, as a general rule, falling return correlations make the whole market less volatile. Realized volatility of the aggregate market was low this year, prompting various theories that derivatives trades are artificially dampening market moves.[4] But there’s a simpler explanation: bifurcation that has decreased the correlation of big growth with everything else. I’m not saying that’s the whole story, but it’s one reason for low market volatility in 2024.

Maybe today’s bifurcation is only temporary. Maybe its benefits will soon be overwhelmed by some market-wide calamity. Could be, but for now, bifurcation has de-risked the market.

There’s an old Wall Street saying: “It’s not a stock market, it’s a market of stocks.” Like many old Wall Street sayings, this statement is annoying and useless. Would you tell someone who is going grocery shopping that “it’s not a grocery store, it’s a store of groceries.” No, you would not, unless you are an annoying and useless person.

Here’s a better statement: “It’s not a stock market, it’s a market of big growth vs. everything else.”

Endnotes

[1] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[2] “Big Names in S&P 500 Overshadow the Risk of a Volatility Jump,” Bloomberg, July 1, 2024.

[3] “Beneath the Calm Market, Stocks Are Going Haywire,” The Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2024.

[4] “The Short-Vol Trade Is Back: Why Some Investors Think It’s Driving Tranquility in Markets,” The Wall Street Journal, March 25, 2024.

References

Acadian Asset Management. “Returns to Value: A Nuanced Picture”, November 2019.

Acadian Asset Management. “Growth Versus Value: End of an Era?”, November 2022.

Asness, Clifford S. "The Less-Efficient Market Hypothesis." The Journal of Portfolio Management, 2024.

Baker, Malcolm. “Investor Sentiment for Value and Growth,” December 2024.

Barberis, Nicholas, Andrei Shleifer, and Jeffrey Wurgler. "Comovement." Journal of Financial Economics 75, no. 2 (2005): 283-317.

Frazzini, Andrea, and Owen A. Lamont. "Dumb money: Mutual fund flows and the cross-section of stock returns." Journal of Financial Economics 88, no. 2 (2008): 299-322.

Copyright © Acadian Asset Management