by Rob Arnott, Research Affiliates

Key Points

- Alpha is not merely a simple risk-adjusted return difference; rather, it is the sum of several critical components, including revaluation alpha, structural alpha, and noise.

- When introducing a new factor or strategy, few take the time to test whether its historical success stemmed from upward or downward revaluation alpha.

- Over a 98-year period, U.S. stocks delivered an average annual excess return of 4.5% over long bonds, with revaluation alpha accounting for one-third of that excess return.

- Past returns contain both structural alpha and a likely one-time revaluation alpha; however, the sum of the two is not a reliable method for anticipating future structural alpha.

Rob Arnott is the corresponding author.

This is part of a series of articles adapted from my contribution to the 50th Anniversary Special Edition of The Journal of Portfolio Management.

Introduction

We are all familiar with this SEC-required warning that “past performance does not predict future performance.” And yet we are relentlessly tempted to believe otherwise, that a thoughtful deep dive into past returns can give us information that may portend future returns. The efficient markets crowd would say that this is rubbish. However, ample empirical evidence suggests otherwise, and entire academic, consulting, and publishing industries in finance earn countless billions every year based on the assumption that past performance can predict results.

What aspects of past returns are (at least modestly) predictive of future returns, what aspects are perverse predictors, and what aspects are pure noise?

The investment industry traditionally approaches alpha as a simple risk-adjusted return difference (though many practitioners misuse the term “alpha” by forgoing the risk adjustment). In reality, alpha has multiple dimensions. At a minimum, historical measures of alpha consist of three constituent parts: structural alpha, revaluation alpha, and noise. If our goal is to find structural alpha—alpha that may be a reliable future source of return—then we should attempt to measure these constituent parts, so that we are not deceiving ourselves and our clients.

“[A]lpha has multiple dimensions. At a minimum, historical measures of alpha consist of three constituent parts: structural alpha, revaluation alpha, and noise.”

The easy—and pernicious—one is revaluation alpha. If a stock doubles and its underlying fundamentals are unchanged, no sensible investor would expect that these past returns are a useful predictor of future returns. Indeed, unless the fundamentals subsequently catch up to the price, strong past returns may presage weak future returns. In “The Equity Risk Premium: Nine Myths,” we showed that even a 98-year history of U.S. stock and bond returns can lead us astray as a direct consequence of revaluation. Over that long history, revaluation contributed nearly one-third of the 4.5% excess returns for U.S. stocks relative to long bonds. We can go a step further in the domain of portfolios, factors, and strategies with the concept of “revaluation alpha.”

When academic journal articles announce new and improved factors and practitioners offer new and improved factor strategies, few (if any) take the time to test whether some of the past success of the factor or strategy may be a consequence of upward (or downward) revaluation. Why should they? If a positive historical alpha is a product of upward revaluation, why would a professor undermine prospects for tenure? And why would a practitioner undermine prospects for soaring AUM by pointing this out? Reciprocally, if a weak historical alpha is a consequence of downward revaluation, that won’t help the prospects for tenure or for growing AUM, perhaps for many years, until that downward revaluation has materially reversed.

“If a stock doubles and its underlying fundamentals are unchanged, no sensible investor would expect that these past returns are a useful predictor of future returns.”

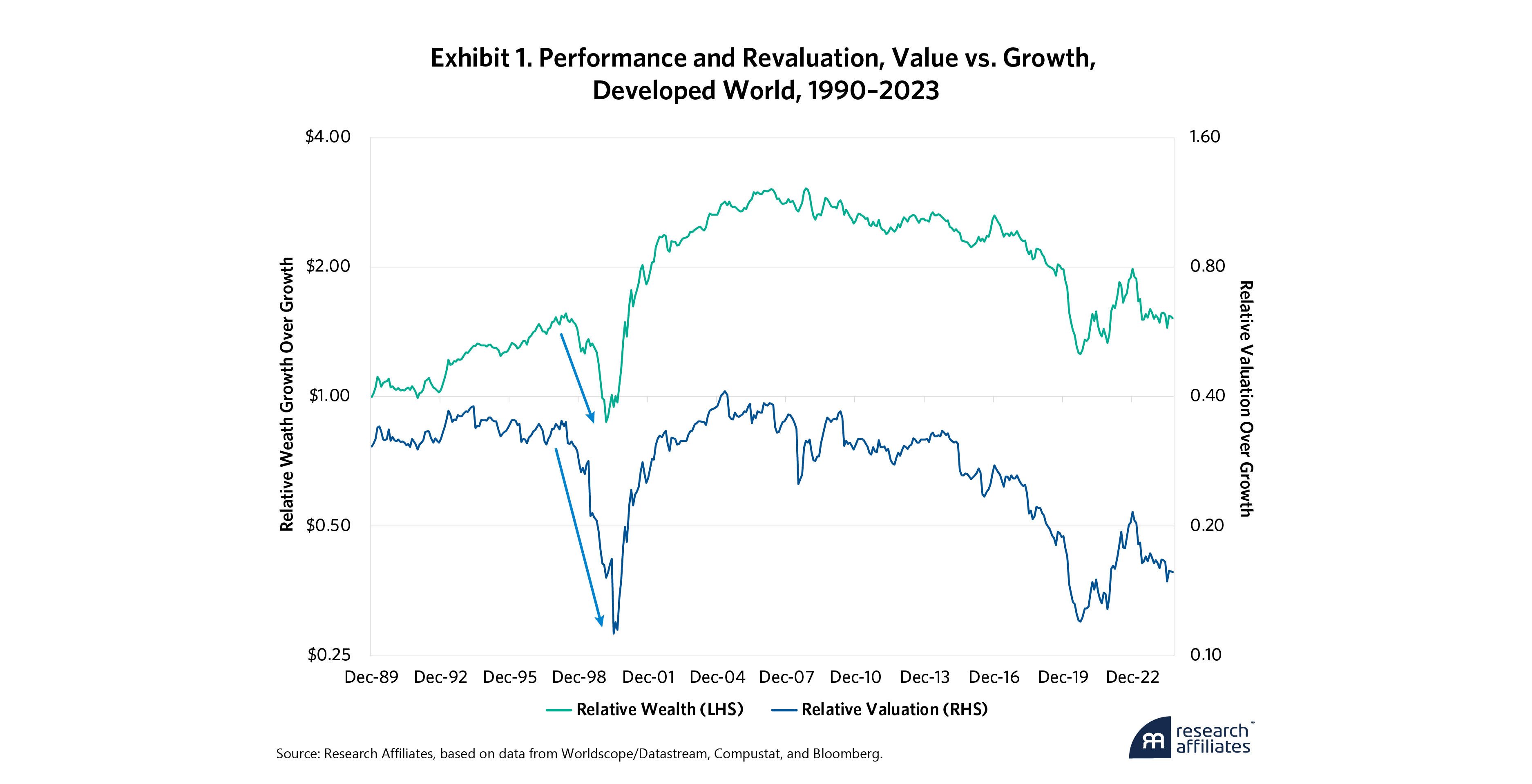

The green line in Exhibit 1 shows the excess return of value stocks relative to growth stocks in developed world markets. In effect, this measures the wealth of a value index investor relative to the wealth of a growth index investor. As with the Fama and French methodology, we look at the least expensive 30% of the market versus the most expensive 30% to focus on the outliers. Unlike Fama and French, we use a blend of four measures of relative cheapness: relative price to book, relative price to cash flow, relative price to sales, and relative price to dividends. We then apply this method to the Developed World, which is roughly equivalent to MSCI World.

The blue line traces the relative cheapness of the value portfolio (again using an average of the four relative valuation multiples) versus the growth portfolio. The value portfolio tends to be cheaper than the growth portfolio, by construction, but this discount can vary over time. In early 2005, the relative valuation peaked at 0.43, meaning the value portfolio was 57% cheaper than the growth portfolio. That may seem like a large discount, but the median relative valuation over this span was 0.32, a 68% discount relative to growth. At the other extreme, value tumbled to one-sixth the price of growth at the peak of the dot-com bubble and again in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crash.

The green and blue lines go up and down together and are highly correlated in their short-term movements. These conjoined movements are, to a first-order approximation, revaluation alpha. Nothing could be simpler, and nothing could be more useless in forecasting future alpha! The mismatch between the short-term movements of the two lines is presumably mostly noise.1 The wedge between the two lines reasonably estimates the historical structural alpha.

Revaluation alpha can be an enormous part of the historical returns that we observe. The blue arrow in Exhibit 1 shows that, from May 1998 to February 2000, the value investor’s wealth relative to the growth investor’s wealth plunged a horrific 44%, from 1.56 to 0.87. During that same span, the valuation of the value portfolio relative to the growth portfolio tumbled from 35% to 15%, an even larger 57% drop in relative valuation multiples. This 57% drop constitutes a “revaluation alpha” of –57%. If the portfolio relative performance was better than the revaluation alpha (–44% versus –57%), then the underlying fundamentals of the value portfolio—its sales, cash flow, book value, and dividends—were improving relative to the growth portfolio, albeit more because of rebalancing than organic growth.2

The blue relative valuation line has a mild tendency towards mean reversion. This is common for almost all factors and investment strategies. There is also a growing wedge between the two lines, which might be a crude approximation of the “structural alpha” of the value factor. Even during the harrowing value meltdown from March 2007 through August 2020, when the value investor’s relative wealth fell by 56%, from 3.14 to 1.39, the relative cheapness of value fell from 0.40 to 0.13, a 67% decline in relative valuation. If relative valuations for value stocks, relative to growth stocks, were the same in the summer of 2020 as in the spring of 2007, value stocks would have outperformed growth stocks by a solid margin.3 As with the value crash during the dot-com bubble, even as value stocks were underperforming growth stocks, the companies in the value portfolio were outgrowing the growth companies!4

Beware the Allure of Backtests

We coined the expression “revaluation alpha” in 2016 and observed that factors and strategies, like stocks and sectors, should have a typical premium or discount to the market that corresponds to their relative likely growth rates, profit margins, popularity, or scale. Business vulnerabilities might also enter the picture. For example, businesses that are more sensitive to the economic cycle, are smaller or less diversified, or face regulatory headwinds might command lower multiples. We observed that mean reversion towards past norms for relative valuation should lead to a negative correlation between the current relative valuation and the future performance of a factor or strategy.

“[F]actors and strategies, like stocks and sectors, should have a typical premium or discount to the market that corresponds to their relative likely growth rates, profit margins, popularity, or scale.”

We also suggested the past returns included both a (presumably) non-recurring revaluation alpha and a structural alpha. We pointed out that the sum of the two would be a flawed and misleading way to estimate the future structural alpha of the strategy. Finally, we highlighted, as many others have before and since, that many factors and strategies are products of aggressive data mining. The most pernicious form of data mining is using a backtest to improve the backtest and then concluding that the backtest is a reasonable basis for setting future expectations. The quant community, both in academe and asset management, is addicted to backtests. Too many academics and practitioners present heavily data-mined backtests as reasonable expectations for future returns. The allure of achieving tenure or large AUM encourages this form of intellectual dishonesty.

“[M]ean reversion towards past norms for relative valuation should lead to a negative correlation between the current relative valuation and the future performance of a factor or strategy.”

Copyright © Research Affiliates

Footnotes

1. I do not suggest that “noise” is random. Rather, it is a combination of all the news, emotions, and shocks that are part of neither the revaluation alpha nor the structural alpha. Noise itself can be nuanced and worthy of study.

2. Much of this is attributable to what Eugene Fama and Kenneth French call “migration.” Suppose a value portfolio is reconstituted annually. Stocks that are no longer cheap are kicked out and replaced with new deep-value names. This means that every rebalance bumps the valuation ratios (price/earnings, price/book, price/sales, and price/dividends) down. This boosts the portfolio’s earnings, book value, sales, and dividends for every $100 we have invested. The opposite happens with the growth portfolio. Still, many investors would be shocked to learn that the Russell 1000 Value Index has seen earnings and dividend grow pari passu with the Russell 1000 Growth Index this century to date. Even during a span when growth stocks have been vastly outperforming value stocks, a portfolio of value companies has grown its earnings, dividends, book value, and sales just as well as a portfolio of growth companies.

3. Consider the arithmetic of comparing relative performance revaluation. A value investor has underperformed a growth investor by 56%, thereby ending the 13½ years with a scant 44 cents of wealth for each dollar of growth investor wealth. The relative valuation is 33% of its early-2007 levels. This means that if relative valuations were the same in 2020 as in 2007, the value investor would have been 33% wealthier than the growth investor (44/33 = 133%) at the end of this bleak span for value. Absent the tumbling relative valuation of value stocks, the value factor worked fine in recent decades.

4. See Arnott, Robert D., Campbell R. Harvey, Vitali Kalesnik, and Juhani T. Linnainmaa. 2021. “Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated." Financial Analysts Journal, 77 (1): 44–67.

References

Fama, Eugene F. 1976. Foundations of Finance, New York, NY: Basic Books

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1992. “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns.” Journal of Finance 47 (2): 427–465.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1993. “Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics 33 (1): 3–56.

Arnott, Rob, Noah Beck, and Vitali Kalesnik. 2016. “Timing ‘Smart Beta’ Strategies? Of Course! Buy Low, Sell High!” Research Affiliates.