by Jurrien Timmer, Director of Global Macro, Fidelity Investments

This market cycle is aging, but still stomping.

Key takeaways

- Compared with historical bull markets, the current bull market may still have room to run.

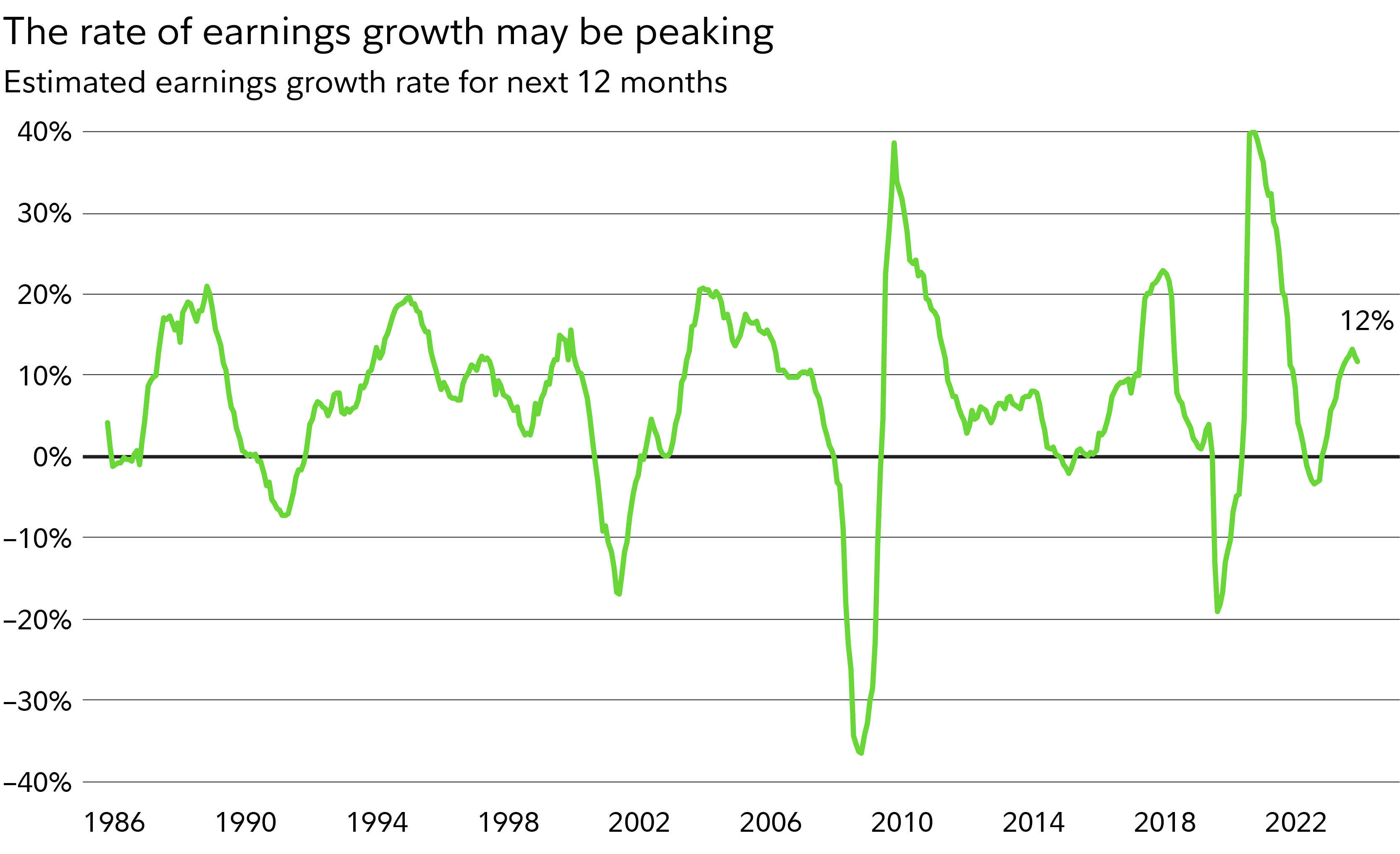

- The rate of earnings growth may be peaking—with earnings still growing but not accelerating. This could be indicative of a maturing business cycle.

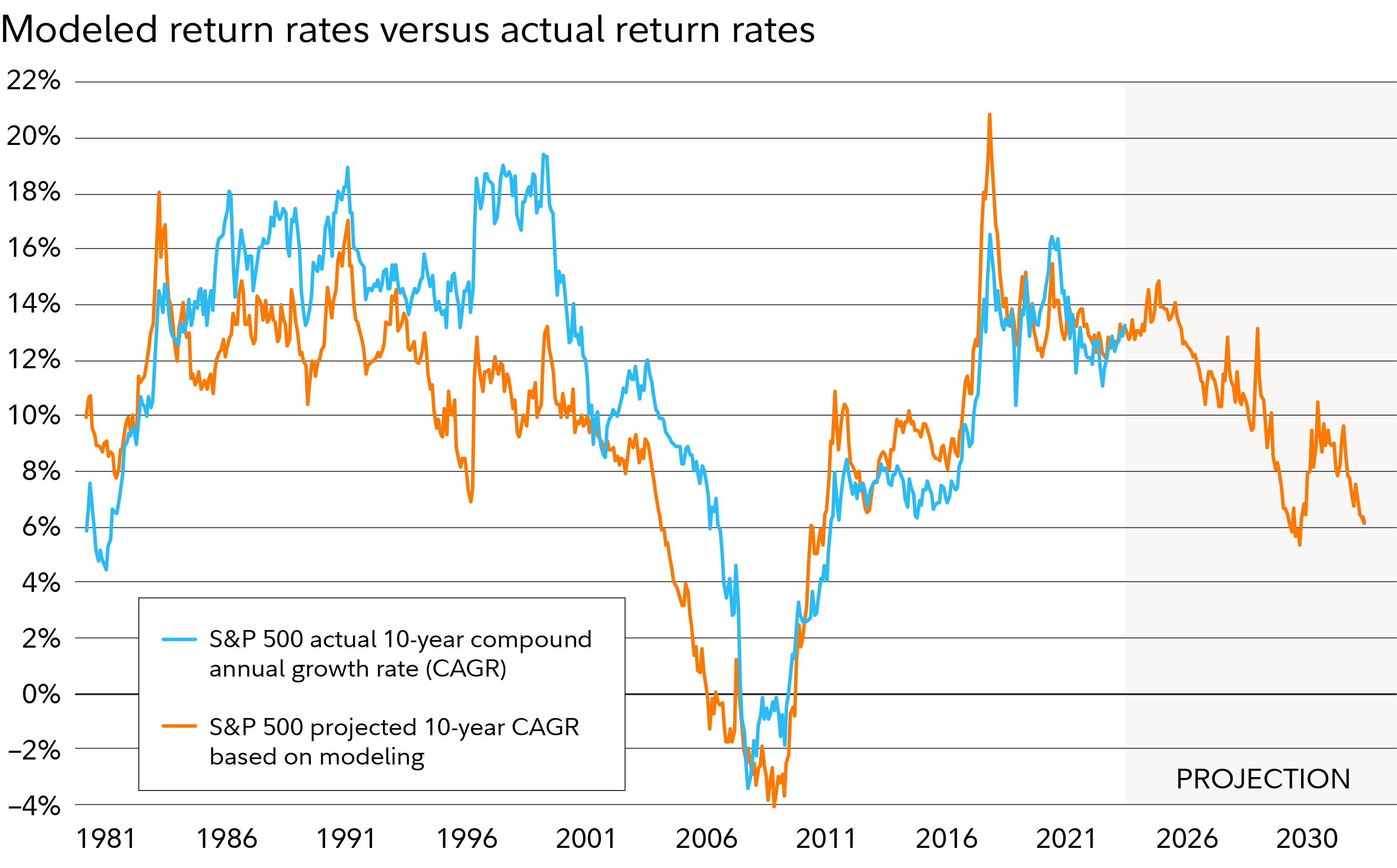

- At some point in the coming years, the US may transition from a period of above-average to below-average (but still positive) returns.

- In the shorter term, I've got my eyes on the pace of Fed rate cuts and whether China's recent monster rally is the start of a bigger shift.

We are approaching the 2-year anniversary of this bull market, which began on October 13, 2022, as the S&P 500® bounced off its lows from the last bear market. So it’s a good time to take stock of both the market’s shorter- and longer-term developments.

The health of the bull

At 24 months young and 66% strong on a total-return basis, this bull remains modest by historical standards. Over the past 100 years, bull markets have lasted a median of 30 months and produced median total returns of about 90%. To me, that comparison suggests we might still only be in the 7th inning.

That impression—of an aging but still-marching cycle—is reinforced by the state of earnings. Earnings season for the 3rd quarter will soon be upon us, with estimated growth rates for calendar 2024 and 2025 holding steady at 9.3% and 14.2%, respectively. However, as the chart below shows it does appear that the rate of growth may be peaking here—based on estimated earnings for the next 12 months.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Estimated growth rate based on consensus analyst estimates of earnings per share for S&P 500 constituent companies over subsequent 12 months. Monthly data as of October 7, 2024. Sources: First Call, I/B/E/S.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Estimated growth rate based on consensus analyst estimates of earnings per share for S&P 500 constituent companies over subsequent 12 months. Monthly data as of October 7, 2024. Sources: First Call, I/B/E/S.

In other words, earnings seem to still be growing, but they might no longer be accelerating. This indicates a maturing business cycle.

The state of the long-term cycle

That’s how I might describe the state of the cyclical, or shorter-term, bull market (meaning the one that started 2 years ago). But I also believe we’re in the middle of a secular, or longer-term, bull market—meaning a multi-year period when the market’s average returns exceed historical long-term average returns. This secular bull market was born in 2009, by my measure, and remains alive and well, although getting on in years. By comparing it to similar historical secular bull markets, such as the 1949–1968 and 1982–2000 periods, I’d estimate it to be in about the 8th inning or so.

One model that has proved to be particularly prescient through this period has been the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio, or CAPE model. This model states that long-term valuation ratios are predictive of forward returns—with high valuations typically preceding lower returns, and vice versa. Rather than simple price-earnings (PE) ratios, I prefer to measure valuation with the 5-year price-to-total-cash ratio (with total cash including dividends and share buybacks). As the chart below shows, this model has been nailing it, with the actual 10-year return rate through September of 13.3% coming in very close to the model’s prediction 10 years ago of 14.8%.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Projected returns are based on a regression model using the 5-year price-to-total-cash ratio as an independent variable and the subsequent 10-year compounded annual growth rate as a dependent variable. Price-to-total-cash ratio compares price level to dividends and stock buybacks. Monthly data since 1949. Sources: Haver, Factset, FMRCo.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Projected returns are based on a regression model using the 5-year price-to-total-cash ratio as an independent variable and the subsequent 10-year compounded annual growth rate as a dependent variable. Price-to-total-cash ratio compares price level to dividends and stock buybacks. Monthly data since 1949. Sources: Haver, Factset, FMRCo.

What is this model’s crystal ball currently predicting? Past performance is of course no guarantee of future results. But if my version of the CAPE model maintains its prescience, we could see the market’s rate of growth peaking out in 2026 and then starting to decelerate—not to negative returns but to positive returns below the long-term historical growth trajectory.

Last week's jobs reports and the Fed

Meanwhile, the Fed seems to have threaded the needle just right (so far). The central bank has now started the process of adjusting policy from restrictive to neutral—essentially starting to take its foot off the brakes and moving toward letting the economy just coast. By my estimate, a “neutral” rate for the fed funds rate (meaning a rate that neither accelerates nor slows the economy) might be around 3.5% to 4%.

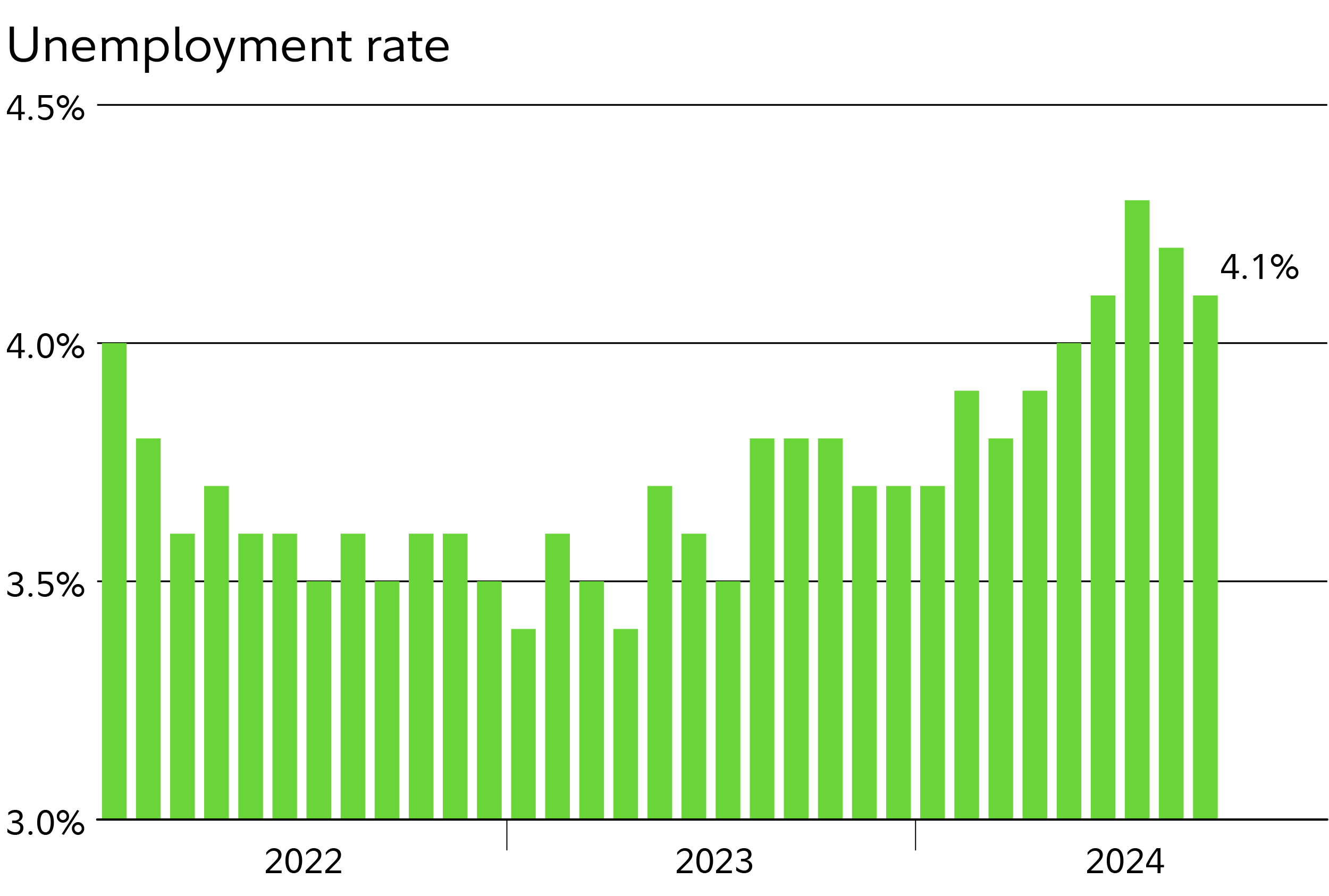

The rate of inflation continues to edge closer to the Fed’s target, and the employment market has worked off its pandemic-era excess labor demand. While there were concerns in late summer over the labor market when unemployment suddenly jumped up to 4.3%, last week’s employment report and Job Openings and Labor Turnover (or JOLTs) report, showed the labor market potentially reaching a state of balance—with the unemployment rate falling to 4.1%, its second monthly decline in a row.

Data as of October 4, 2024. Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Data as of October 4, 2024. Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Now the trick is for it to stay there. We know from history that the labor-market pendulum tends to swing from one extreme to another. For it to stop right here would be quite an achievement.

Following those strong jobs reports, the market has walked back its expectations of multiple 50-basis-point jumbo rate cuts from the Fed. It’s now, again, expecting a more normal trajectory of 25-basis-point cuts from here (which makes sense).

The rally in China

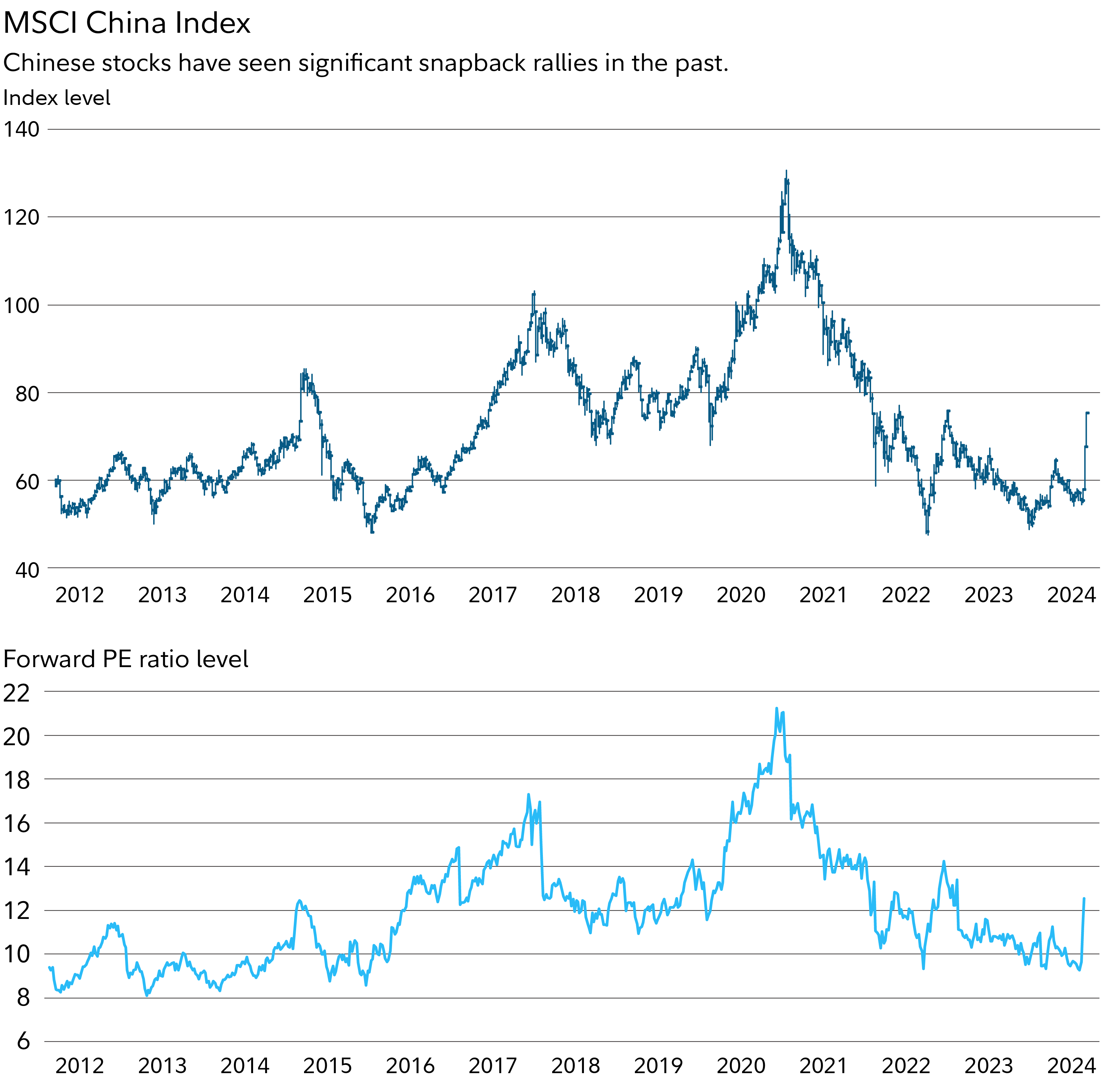

The Chinese stock market has generally struggled since 2021, due to lingering effects of its strict COVID-related lockdowns, increasing business regulation, and troubled housing market. Then in the past couple of weeks the Chinese market staged a monster rally, in reaction to news of a new round of policy stimulus. Could the Chinese market be turning the page on a new chapter? And more broadly, could we be on the cusp of a major global rotation, which would bring non-US stocks into a period of leadership over US stocks?

We could be, but ultimately for a period of lasting outperformance to begin for non-US stocks, they will need to produce better relative earnings, as history has shown that relative performance tends to follow relative earnings.

For China, there may be some potential on that front. Relative earnings between China and the US have rarely been as stretched as they are today, and the progression of earnings estimates are starting to converge from extreme levels.

Additionally, Chinese valuations are depressed, which allows for the occasional snapback rally. So far, the PE ratio of the MSCI China Index has risen by 3 points (based on analyst estimates of next-12-month earnings). As the chart below shows, that’s modest by historical standards—with most rallies over the past 10 years producing 5- or even 10-point gains in the index’s forward PE ratio.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. See disclosures below for more information on the MSCI China Index. Forward PE is defined as the current index level divided by analyst estimates of earnings per share for constituent companies over the subsequent 12 months. Data as of October 7, 2024. Sources: Bloomberg, FMRCo.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. See disclosures below for more information on the MSCI China Index. Forward PE is defined as the current index level divided by analyst estimates of earnings per share for constituent companies over the subsequent 12 months. Data as of October 7, 2024. Sources: Bloomberg, FMRCo.

Nothing is ever guaranteed in markets, but converging earnings plus a large valuation differential could produce more fireworks along the lines of what we have seen these past few weeks.

Copyright © Fidelity Investments