by Jared Franz, Economist, Capital Group

In the 2008 movie, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, the title character played by Brad Pitt ages in reverse, transitioning over time from an old man to a young child. Oddly enough, I think the U.S. economy is doing something similar.

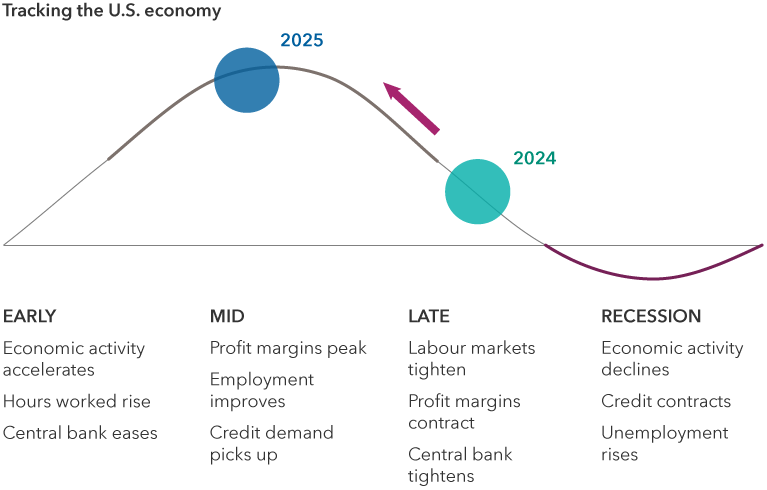

Instead of the typical four-stage business cycle — early, mid, late and recession — we have witnessed since the end of World War II, the economy appears to be transitioning from late-cycle characteristics of tight monetary policy and rising cost pressures back to mid-cycle, where corporate profits tend to peak, credit demand picks up and monetary policy is generally neutral.

The next step should have been recession but, in my view, we have clearly avoided that painful part of the business cycle and essentially moved backward in economic time to a healthier condition.

U.S. economy goes back to the future

Source: Capital Group. Positions within the business cycle are forward-looking estimates by Capital Group economists as of December 2023 (2024 bubble) and September 2024 (2025 bubble). The views of individual portfolio managers and analysts may differ.

How did this happen? Much like the movie, it’s a bit of a mystery, but I think the Benjamin Button economy has resulted largely from post-pandemic distortions in the U.S. labour market that were signaling late-cycle conditions. However, other broader economic indicators that I think may be more reliable today are flashing mid-cycle.

If the U.S. economy is mid-cycle, as I believe, then we could be on the way to a multi-year expansion period that may not produce a recession until 2028. In the past, this type of economic environment has produced stock market returns in the range of 14% a year and provided generally favourable conditions for bonds.

The unemployment rate gap

Stay with me for a moment while I explain my methodology. Instead of using standard U.S. unemployment figures to determine U.S. business cycle stages, I prefer to look at the unemployment rate gap. That’s the gap between the actual unemployment rate (currently 4.2%) and the natural rate of unemployment, often referred to as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or NAIRU. That number typically falls in a range from 5.0% to 6.0%. Simply put, it’s the level of unemployment below which inflation would be expected to rise.

While this is a summary measure of dating the business cycle, it is based on a more comprehensive approach that looks at monetary policy, cost pressures, corporate profit margins, capital expenditures and overall economic output.

The unemployment gap is a measure that can be tracked each month with the release of the U.S. employment report. The reason it has worked so well is because the various gap stages tend to correlate with the underlying factors of each business cycle. For example, when labour markets are tight, cost pressures tend to be high, corporate profits fall and the economy tends to be late cycle.

Unemployment data signals rise of a mid-cycle economy

Source: Capital Group. The unemployment rate gap is the distance between the actual unemployment rate and the natural rate of unemployment. Business cycles are forward-looking estimates by Capital Group economists. The views of individual portfolio managers and analysts may differ. As of July 31, 2024.

This approach also worked nicely in pre-pandemic times, providing an early warning signal of late-cycle economic vulnerability in 2019. That was followed by the brief COVID recession from February 2020 to April 2020.

It’s likely that the pandemic has distorted the U.S. labour market, structurally and cyclically. For example, the labour force participation rate experienced an unprecedented decline as global economic activity came to a virtual standstill. That was followed by a remarkable rebound in the participation rate above pre-pandemic levels for prime-age (25- to 54-year-old) workers.

In other words, traditional ways of looking at the unemployment picture are now less useful tools for calibrating broader economic conditions. They’ve become less correlated with classic business cycle dynamics. Not recognizing these changes can lead to overly optimistic or overly pessimistic assessments of the cycle.

Market implications: Stocks and bonds could do well

My macroeconomic view drives my equity market view. As I said, an economy that is mid-cycle has tended to produce equity returns of approximately 14% on an annualized basis. Small-cap stocks have generally outpaced large caps, value has outpaced growth, and the materials and real estate sectors have generated the best returns. These figures are based on a Capital Group assessment of market returns from December 1973 to August 2024.

As always, it’s important to acknowledge that past results are not reflective of results in future periods. But if the U.S. economy continues to grow at a healthy rate — 2.5% to 3.0% in my estimation — that should provide a nice tailwind for equity prices. Over long periods of time, when the U.S. economy grows above its potential 2.0% growth rate, that type of environment has generally supported better-than-average stock market returns.

A mid-cycle economy has provided favourable market returns

Sources: Capital Group, MSCI. Data is monthly from December 1973 to August 2024. Total index data is Datastream U.S. Total Market Index from December 31, 1973, through December 31, 1994, and MSCI USA Index data thereafter. Sectors are Datastream sectors from December 31, 1973, through December 31, 1994, and GICS (MSCI) sectors thereafter. Business cycles are forward-looking estimates by Capital Group economists. The views of individual portfolio managers and analysts may differ. As of July 31, 2024.

Mid-cycle economies have also generally produced a favourable backdrop for fixed income markets. During the same period referenced above, long-term U.S. government bonds returned 4.7% on an annualized basis, while long-term corporate bonds returned 5.0%.

If the U.S. Federal Reserve continues to cut interest rates, I believe that could provide an even more favourable environment for bonds over the next few years. Given my positive economic outlook, I don’t think the Fed will reduce rates as much as the market expects. Inflation hasn’t been defeated quite yet. It’s still slightly above the Fed’s 2% target, so following last week’s 50 basis point cut, I think central bank officials will be cautious about future rate cut actions.

Election uncertainty? Not really

With U.S. elections about a month away, you may be wondering if my outlook for the economy and markets will change depending on the outcome. The answer is no. Over the years, I’ve learned to be election agnostic. Promises made on the campaign trail often look nothing like the policies enacted after Election Day and, therefore, I generally avoid taking political considerations into account.

As an economist, I believe political gridlock is not all bad, and it has tended to be the norm in recent decades. I think we are likely to see a split government again in 2025, with neither party gaining full control of the White House, the Senate and the House of Representatives. That should narrow the potential for wild policy swings and put the focus back on the fundamentals: the economy, the consumer and corporate earnings.

Jared Franz is an economist with 18 years of investment industry experience (as of 12/31/2023). He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Illinois at Chicago and a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Northwestern University.

Copyright © Capital Group