by AJ Rivers, CFA and Lucas Krupa, AllianceBernstein

The Fed’s close monitoring and well-signaled tapering of QT should prevent disruptions to the short-term funding markets—despite converging risks.

Declining cash reserves across the US financial system have some market observers predicting a liquidity crunch in the funding markets. We disagree. To understand why, it helps to understand how we got here.

The Federal Reserve’s Balancing Act

In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the Federal Reserve ensured liquidity in the economy by buying massive amounts of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. This quantitative easing (QE), along with other government stimulus measures, ballooned the Fed's balance sheet, flooded the financial system with cash and greased the economic skids.

But QE eventually resulted in excess liquidity in the short-term funding markets—that is, too much cash and too few places to invest it. Since 2022, the Fed has been draining that excess liquidity through quantitative tightening (QT). To shrink its balance sheet, the Fed has stepped back from its role as a major buyer of debt securities and has instead allowed debt on its balance sheet to mature without reinvesting the proceeds.

That leads us to where we are now, with QT on the path to a supply and demand imbalance between cash and securities. For some market observers, this evokes memories of September 2019, when the Fed fumbled QT, bringing short-term funding markets to a standstill.

In 2019, the Fed, having miscalculated the amount of bank reserves needed to keep the system liquid, kept QT going for too long, even as Treasury issuance surged and money market funds saw dramatic outflows. Simply put, there wasn’t enough cash available to meet the supply of securities. Funding rates spiked to 10%, and the Fed had to halt QT abruptly and provide an emergency lending facility to restore liquidity.

But this time is different, in our view. Today, the Fed is working carefully to achieve equilibrium as it balances supply and demand. Fed officials are communicating early about plans to taper QT. And the Fed is closely monitoring gauges of liquidity in the funding markets so that it can chart a smooth course. This should help avoid a repeat of 2019 and ease investor concerns.

Indicators Point to Continued Excess Liquidity—for Now

One gauge of excess liquidity is the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) facility, which money market funds and other nonbank financial institutions use to put excess cash to work—essentially making overnight loans (repo transactions) to the Fed at a fixed rate. The RRP is a useful tool of last resort when short-term funding alternatives are in short supply. Only a year ago, RRP reserves ballooned to roughly $2.5 trillion.

But more recently, the RRP has seen declining use; not only is the Fed unwinding its balance sheet, but money market funds have more attractive alternatives in which to invest cash. At this pace, the RRP could eventually be drained before the end of the year, marking an end to excess liquidity if it falls below $100–$200 billion, according to market consensus. But we’re not there yet. Currently, RRP use is north of $500 billion (Display), which the Fed has deemed ample.

If the RRP is the Fed’s way to gauge excess liquidity, the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) gauges the amount of insufficient liquidity. The SRF is a permanent version of the emergency measures deployed in 2019. It provides dealers who need financing with the ability to borrow at pre-determined rates by pledging Treasuries and other high-quality securities as collateral. It functions as a backstop in the event that overnight rates spike unexpectedly.

In other words, the SRF shouldn’t see prolonged use unless the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) climbs to or above the current upper bound of 5.5%, which could indicate insufficient funding market liquidity at the current policy rate. Conversely, a SOFR below the current lower bound of 5.3%—the floor at which money market funds can currently execute overnight transactions in the RRP—would signal excess liquidity (Display).

As long as the SOFR is somewhere within this range—and it still is—supply and demand are in balance. As use of the RRP dwindles, SOFR will eventually drift toward the upper bound of 5.5%, signaling that the Fed should taper QT faster, or end it altogether—particularly if the SRF sees prolonged use.

Liquidity Risks Are Converging

The Fed is keeping an eye on factors that could accelerate liquidity drain. For one, money market funds saw massive inflows while the Fed hiked rates; now that the central bank is on the cusp of easing, we expect flows to shift back into the bond market. The resulting drop in assets in money market funds would speed the downward trend in RRP use.

Adding to the potential supply and demand imbalance, the US Treasury is expected to auction $2.0–$2.5 trillion in net issuance to fund 2024 deficit spending. Big banks typically fill this kind of void in the short-term funding markets by stepping in as Treasury market markers, which can help restore market liquidity. But reforms enacted following the global financial crisis require banks to set aside minimum amounts of capital against assets—including US Treasuries. These regulations have discouraged large banks from acting as intermediaries and constrain their ability to assume additional risk.

Fortunately, the Fed is acutely aware of these liquidity risks and appears to have learned from its missteps in 2019. Already, the Fed has telegraphed its intention to taper QT. The SRF will serve as a backstop should the Fed mismanage reserves again. Tapping the SRF could be an early signal that supply and demand are getting out of balance.

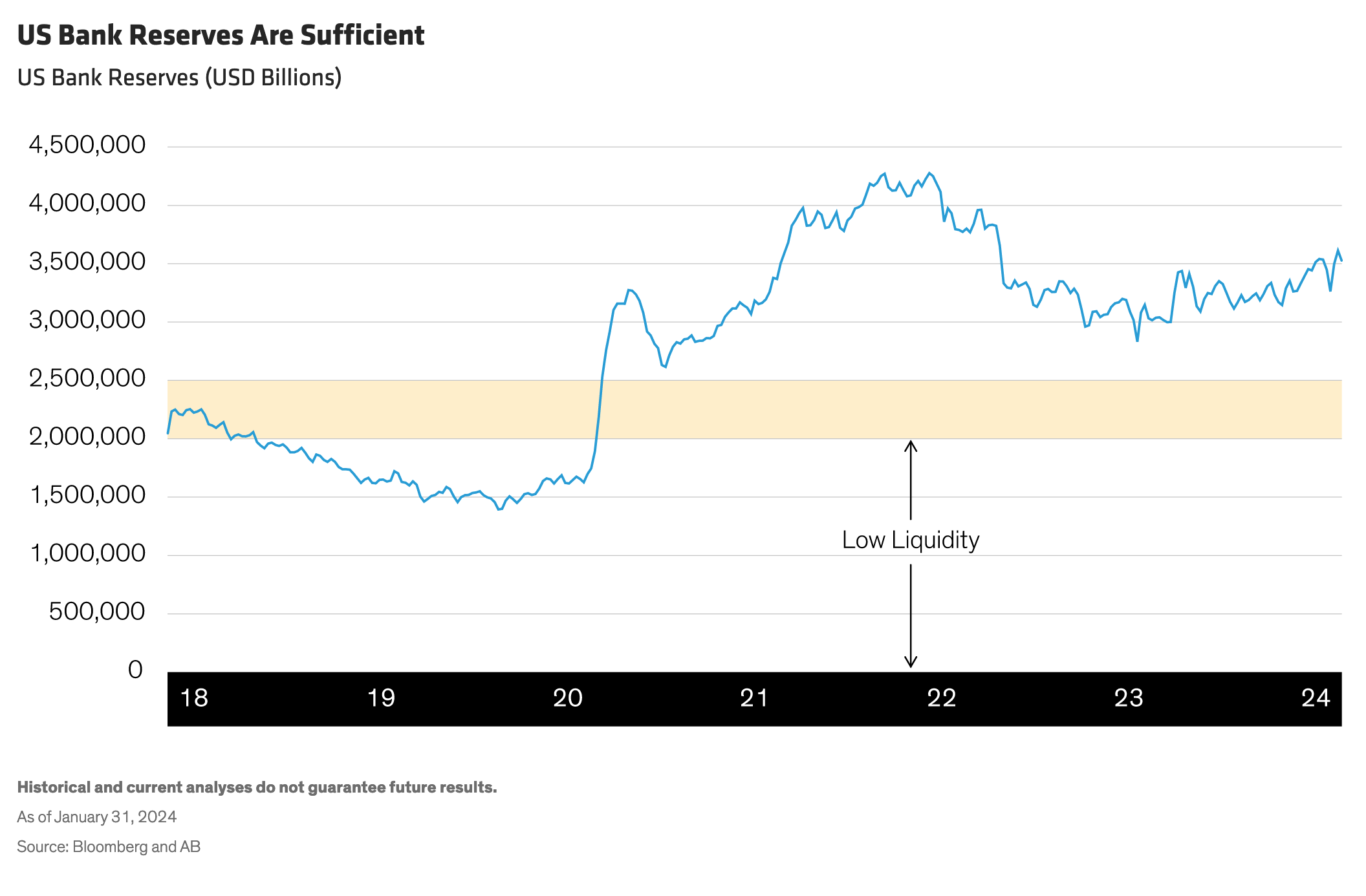

In the meantime, we are monitoring the short-term funding markets, while also keeping an eye on bank reserves. We agree with the market consensus that reserves should be between $2.0 trillion and $2.5 trillion to maintain sufficient liquidity and keep the financial system operating smoothly. Currently, reserves stand at $3.5 trillion (Display), which Fed officials have described as “more than ample.”

Stay Informed and Monitor Risks

With the Fed closely monitoring the situation, a liquidity squeeze in the short-term funding markets seems unlikely, in our view. Nevertheless, investors should keep an eye on risks that could accelerate a liquidity drain and create disruptions in the funding markets. By staying informed and working with informed, active managers, investors can adjust their strategies as conditions change.

*****

About the Authors

AJ Rivers is a Senior Vice President and Head of US Retail Fixed Income Business Development. Prior to joining AB in 2022, he was the director of Product Strategy at Lord Abbett. Throughout his career, Rivers has been directly involved in the rates and credit markets, and has directed the product development and competitive positioning of investment strategies in traditional and alternative assets. He has held roles in trading, risk management, portfolio analytics and product strategy. Rivers attended the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University and graduated from the University at Buffalo for undergrad. He is a CFA charterholder, a Financial Risk Manager (FRM) and a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA). Location: Nashville

Lucas Krupa is a Senior Vice President and Senior Portfolio Manager on the Fixed Income team, responsible for the management of money-market assets, including AB’s 2a-7 government money-market fund, and the trading of all money-market securities. Prior to assuming this role in 2013, he was a credit research associate on AB’s Fixed Income Credit Research team. Krupa joined the firm in 2010 as an associate in the Fixed Income Rotational Program, rotating through the Portfolio Management, Credit Trading and Credit Research teams. He holds a BBA (summa cum laude) in finance with a minor in economics from Pace University. Location: New York