by Sonal Desai, CIO, Fixed Income, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

A dovish nudge in the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) November press conference pushed markets to again price a significant monetary easing as early as mid-2024. Our Franklin Templeton Fixed Income CIO Sonal Desai sees this market reaction as an excess of exuberance that sets the stage for more volatility. She shares her latest insights on the policy outlook and the implications for investors.

For the best part of this tightening cycle, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been playing a tug of war with financial markets, with the central bank trying to persuade investors that a period of higher interest rates is needed to bring inflation durably under control, and investors resisting or even “fighting” the Fed.

Over the past three months, the Fed seemed to have gradually prevailed, and bond yields rose to nearly 5%. The Fed, however, might have overestimated the extent to which financial markets had really come around to its view. At the November Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell gave a gentle dovish nudge, not just with the expected decision to hold rates, but also in suggesting that growth might already be running under its (temporarily elevated) potential pace, and de-emphasizing the importance of the Fed “dots” (which point to one more hike). A handful of weaker-than-expected economic data compounded the impact on market prices.

So as Powell noted that the Fed’s inflation fight was getting important help from tighter financial conditions, investors promptly drove financial conditions in the opposite direction, with lower bond yields and higher stock prices.

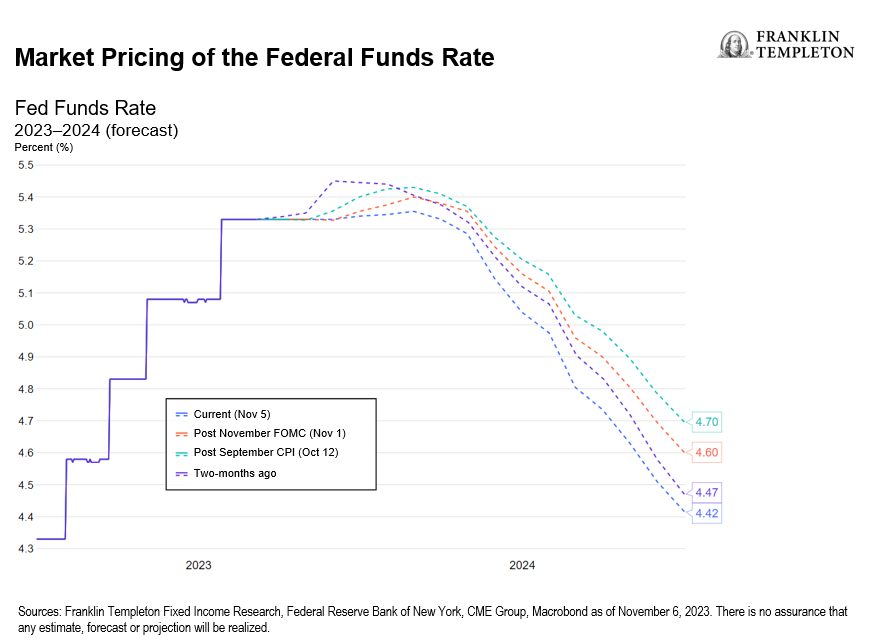

Powell said the Fed still needs to answer the question of whether monetary conditions are tight enough, and only after it has found the answer will it move to pondering for how long conditions should remain tight. However, investors quickly provided their own answers: Monetary policy is plenty tight already, and by the middle of next year it should start loosening at a brisk pace, to cut the fed funds rate to close to 4% by end-2024.1

Satisfied with the progress achieved, Powell gave investors just a gentle nudge of encouragement, and they ran with it in a burst of what I see as an excess of exuberance.

The Fed is still grappling with three difficult questions:

- How persistent is inflation?

- How fast is the economy likely to lose steam?

- Where does the neutral policy rate sit?

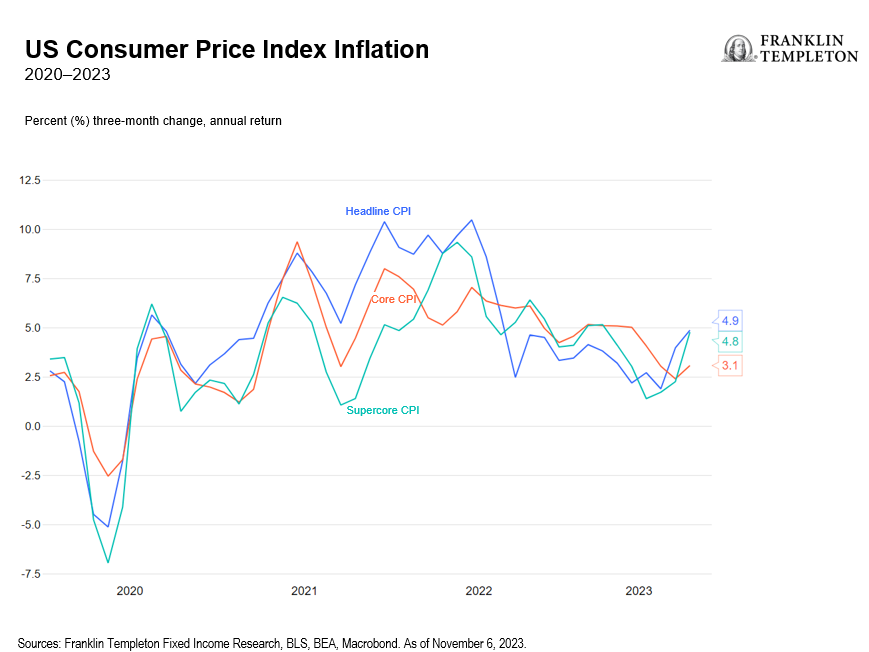

Compared to a year ago, inflation is now quite close to target—and yet still too far away. There are a variety of inflation measures that analysts throw around: consumer price index (CPI), personal consumption expenditures (PCE), headline, core, 12-month change, monthly change annualized. Some look very reassuring, others much less so.

My preference is to look at core CPI and take the month-on-month change, which gives us the current pace of price growth unaffected by older base effects. That rate, annualized, is still bouncing around a lot. In July it was just 1.9%; in September it was 3.9%. The three-month average is still above 3%; the six-month average is close to 4%.2

Other measures like headline CPI and supercore CPI—which strips out not just food and energy but also housing, and has been often highlighted by Powell—run even higher, with a three-month average close to 5%, as the chart below shows.

Exhibit 1: Nearer-Term CPI Momentum Picks Up

Inflation is not quite under control yet, and too volatile for comfort, especially with the risk of another energy shock always just around the corner. Plus, a number of structural factors, from demographics to the green transition, suggest that long-term inflation pressures will be more robust.

The US economy has proved extremely resilient, expanding at a nearly 5% annualized pace in the third quarter. As I have argued in previous “On My Minds”, this should not be too surprising; households had a healthy cushion of excess savings and fiscal policy remains very loose. Nonetheless, funding costs for households and corporates have risen across the board, and despite healthy balance sheets, monetary tightening is beginning to bite. The latest data are consistent with some deceleration in economic growth and job creation. Monetary policy just might be tight enough to cool the economy to the right sub-potential pace. Maybe.

As far as the neutral policy rate is concerned, I believe the Fed is too dovish; it still seems to think that once things have settled, short-term rates can again be quite low, though not as low as in the post-global-financial-crisis (GFC) period. My own view remains that the neutral policy rate will prove to be closer to 4% or higher rather than the 2.5% still envisaged by the Fed.

With all this, regarding the forthcoming monetary policy decisions, the Fed likely feels it is now in fine-tuning territory, justifying a prudent approach—watch the data, and decide meeting by meeting what to do next.

I would not rule out the need for another rate hike yet—inflation pressures remain resilient with plenty of scope for unwelcome surprises. And I strongly believe that policy rates will have to remain at-or close to current levels for the better part of 2024 in order to secure the sustained decline in inflation to the 2% target that the Fed is pursuing.

Exhibit 2: Markets Dialing Up Rate Cut Expectations after November FOMC and October Nonfarm Payrolls

However, Powell’s dovish nudge at the November press conference has sufficed to push markets in a completely different direction: They have not only priced out any further rate hikes, but now expect about a full percentage point of rate cuts next year, starting already before mid-year, which seems unreasonably aggressive, in my view. This in turn will now complicate the Fed’s job and in my view, set the stage for more volatility and a likely rebound in yields over the coming months.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

______________

1. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.

2. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Franklin Templeton Fixed Income. As of November 6, 2023.