by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle, Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

Internal priorities and external circumstances have brought China's growth to an inflection point.

The Chinese Communist Party just concluded its 20th National Congress. For the first time in a long while, the Chinese economy was not providing a favorable backdrop for the gathering. Economic growth this year will fall far short of expectations, and there are a range of headwinds on the horizon. How China navigates these challenging conditions will be critical for its future, and for the world.

Following is an examination of some of the central factors that likely occupied attention during this week’s sessions.

Clients Cutting Back

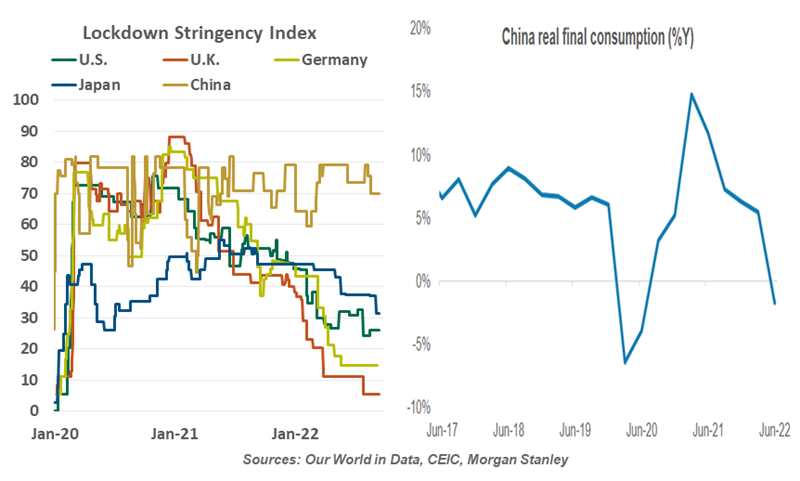

Ahead of the National Congress, there was hope that Chinese policymakers might finally recalibrate their zero-COVID strategy. That optimism swiftly faded. In his two-hour speech, President Xi Jinping reinforced the country’s commitment to the stringent restrictions, noting that it had saved lives.

Lockdowns have certainly limited the consequences of COVID-19 for public health. But they have introduced severe consequences for economic activity. Frequent stay-home orders in key business hubs like Shanghai and Zhengzhou have proven to be a major disruptor for the industrial sector. Strict controls have disrupted logistics, leaving factories struggling for supplies. Frequent testing and quarantine requirements for truckers often contribute to delays in goods reaching the ports for export. Shipping agents are struggling to find sufficient cargo this year, even during peak shipping season.

Any lasting disruption in domestic supply chains will inflict further pain at home and abroad. Weaker export growth will weigh on manufacturing profits, and in turn put pressure on the labor market. Small- and medium-sized enterprises will be the worst affected, accounting for the majority (about 70%) of exports.

Lockdowns have also affected consumption. Households remain cautious amid lingering uncertainty over the virus, and rolling lockdowns have impacted household incomes. Domestic and international tourism by Chinese travelers is still a shadow of its pre-pandemic level.

For these reasons, many still expect China to quietly begin relaxing its COVID restrictions as we move into 2023. But for now, measures to curb the virus are still curbing the Chinese economy.

Hitting The Wall

Property has been the subject of irrational exuberance at many points in history. At one point in the 1980s, the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth more than all of the real estate in California. Lax U.S. mortgage standards supported a massive increase in residential property values during the first decade of this century. Both episodes ended very badly: Japan has never fully recovered from its 1990 crash, and the 2008 financial crises left scars the world over.

The property boom in China looks like it will end badly.

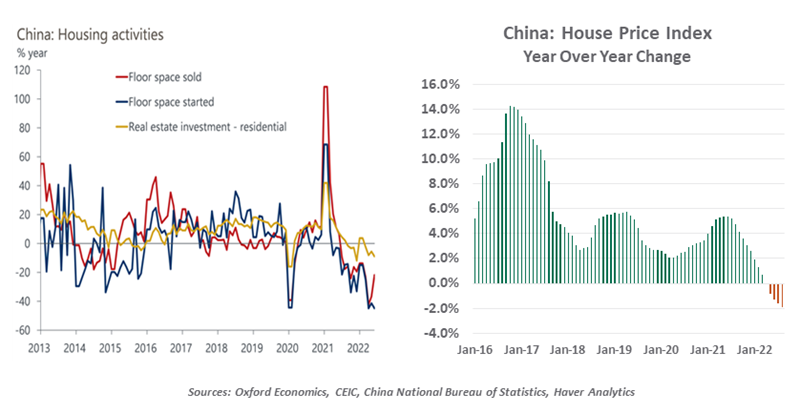

Those cautionary tales may not have been translated into Chinese. For twenty years, property speculation and property prices have fed on one another in China. Regional governments have raised substantial amounts of revenue by auctioning off land for development. Construction companies have profited from the building boom, and seen their market capitalization skyrocket.

It is hard to pinpoint when the psychology surrounding speculative intervals turns from enthusiastic to panicked, but China passed that juncture sometime last year. Home prices are now down on a year-over-year basis, and more than half of major Chinese cities are experiencing property price corrections. Analysts suspect that these official statistics understate the full extent of the malaise.

Leading construction companies are deeply troubled. Evergrande, the country’s second largest developer, is insolvent; others are in a similar situation. Investors and banks that provided credit to the firms are facing substantial losses and diminished capital. Small savers who purchased yet-to-be built residences now suspect that they will never be completed; many have abstained from making mortgage payments as a way of registering their discontent.

The property sector is a much more significant contributor to Chinese gross domestic product than it is in other countries. An estimated 70% of household wealth is tied up in real estate, earning increasingly negative returns. This will not be helpful to consumption or consumer confidence.

It will require substantial sums to recapitalize lenders, complete projects and compensate the aggrieved. China must balance the desire to restore order with the desire to teach a lesson on financial excess and moral hazard. And China is already a deeply indebted country, which might curtail their willingness and ability to finance a bailout.

The spreading recession in real estate is one reason why Chinese growth has been impaired, and why it may remain so for some time.

Trade Ties

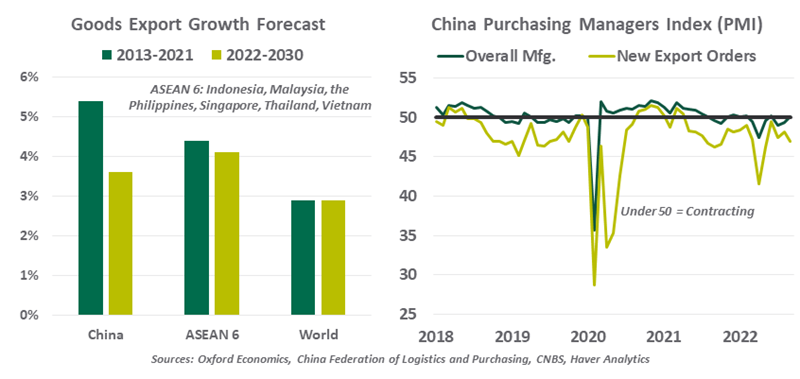

China's economic miracle was led by its emergence as an export powerhouse. However, the days of export-led growth are in the past, and the nation will need to find a new balance of economic output.

Today, China confronts a global economy that is unquestionably slowing. Even under the best terms of trade, the year ahead was certain to be a slow one for exports. China thrived through the pandemic partly because stimulus in Western countries raised demand for imported goods. As a result, China’s export volumes reached new records. With so much demand having been pulled forward, a slowdown in 2023 was preordained.

Trade restrictions aimed at China are becoming more numerous.

But China's recent success came despite an increasingly murky relationship with its trading partners. The signature policy of the Trump administration was an escalating tariff regime on China in retaliation for its alleged anti-competitive import restrictions and government subsidies. Those tariffs remain in force. In early 2020, negotiators came to a "phase one" preliminary trade deal, in which China committed to increase its purchases of U.S. exports. In the two ensuing years, China fell well short of those commitments, even after pandemic disruptions cleared.

Tensions between China and the U.S. are again on the rise, as the Biden administration enacted a new set of restrictions on high-technology exports to China. The new regulations immediately curtail exports of tools to produce advanced computer and memory chips, as well as restricting any U.S. citizen or company from assisting Chinese companies in their chip manufacturing. The restrictions will slow China's ability to develop new applications of artificial intelligence and military capabilities, and ultimately impair their ability to domestically produce cutting-edge technologies.

With barriers to trade only growing, China's future growth will need to come from domestic demand. Today's painful import restrictions may set the stage for homegrown technology advancements in years to come. But for now, the export growth engine is sputtering.

Bring It Home

China's role as the world's factory depended on many connections: a free flow of imported energy and raw materials, foreign direct investment to set up new factories and ready shipping links to ferry finished products to the rest of the world. The system seemed to work well and efficiently, providing many goods at low prices.

But with disruptions continuing for nearly three years, it is now clear that global trade arrangements flew too close to the sun. COVID-19 and its ensuing ripples revealed just how delicate the foundations of global trade really were.

Developed market customers are reconsidering their supply dependencies and alliances. The pandemic made clear the risk of concentrating production in one location, even in a peaceful world. As geopolitical tensions rise, importing nations must contemplate the worst possible outcomes. Business decisions will focus less on cost and more on resilience. This will result in greater opportunities for domestic suppliers and nations that are on consistently friendly terms.

The U.S. CHIPS and Science Act is a prominent example of subsidies to support domestic production of advanced technologies that will be critical for cleaner, more sustainable economic activity. Today, western nations lack capacity to produce many core technologies like semiconductors and rechargeable batteries at scale; with subsidies, the balance of production is poised to shift.

Domestic subsidies are the latest weapon in the trade war.

Zero-COVID only reinforces the business case for moving production elsewhere. With authorities quick to isolate individuals and lock down entire cities, China's manufacturing capability remains impaired. Deliveries of manufacturing orders are no longer reliable.

A de-globalized system will no longer feature one nation as the factory. China will work to preserve all the market share it can, but its client base may shrink in the years ahead.

Coming Clean

China’s reliance on “smokestack” industries may have to be curtailed in the decades ahead. Foul air, water and soil have been causes of complaint among Chinese citizens for many years.

More broadly, efforts to contain global climate change will not be successful without China’s aggressive involvement. China accounts for more than one quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, more than double the next largest contributor.

Getting greener involves transition risk, though, and no country faces a greater risk in this regard than China. Finding lighter industries which can pick up the slack as heavier ones retreat will be critical to sustaining economic growth.

New Age

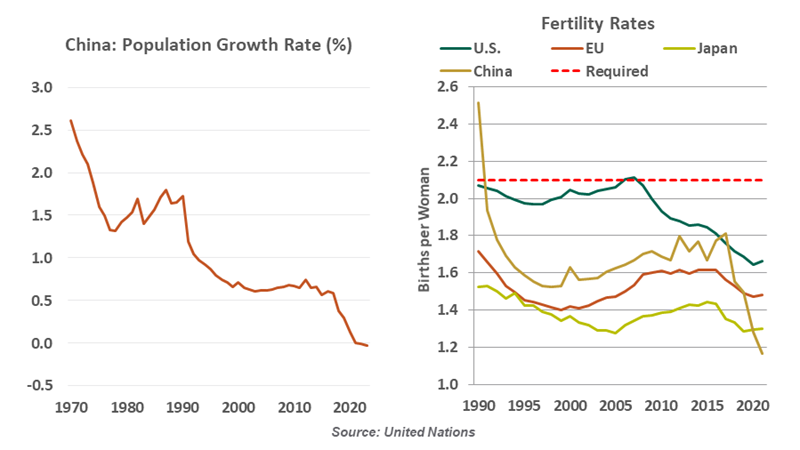

Among the long list of dark clouds hovering over China, demographic change is the most worrisome, with long term implications for growth. All countries are getting older, but China is getting older than most.

China’s population is expected to peak this year, a decade earlier than previously forecasted. This would be the country’s first decline in over sixty years. Falling fertility rates and a rapidly aging population are the key factors behind this shift.

The total fertility rate has fallen to a seven-decade low of 1.16 births per woman, according to United Nations data, far below the population replacement rate of 2.1. The share of the population that is aged 60 years or above has risen from 10% to 19% (over 260 million) in just two decades. That share is forecast to rise to one third of the population before 2050. At this rate, China will reach the status of a super-aged society even sooner than demographically challenged nations like Japan. Despite the end of the one-child policy seven years ago and introduction of the three-child policy in 2021, birth rates haven’t improved.

China has one of the biggest aging problems in the world.

High parenting costs and lack of access to public services such as childcare and education have disincentivized couples from having children. China’s zero-COVID policy has also played its part, limiting social opportunities and adding to financial and employment insecurities.

The implications of an aging Chinese society will be vast and varied. An increasing old-age dependency ratio and shrinking share of working-age population will change the patterns of saving and investment. Fewer workers will create shortages in the labor supply, impairing productivity and potential output. Declining population would mean less domestic consumption, delaying the pivot towards a consumption-driven economy. China’s social security system is already the largest network in the world, so a rapidly aging society will further strain the nation’s fiscal resources.

Reforms to develop a private pension system and to mobilize private sector investment in elderly care are works in progress. Demographically, China is transitioning from dividend to deficit.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Copyright © Northern Trust