by Carl Tannenbaum, Chief Economist, Northern Trust

Renewed increases in energy prices come at a bad time in the battle against inflation.

I am of the generation that dealt with the energy shocks of the 1970s. I recall my father waiting in long lines to get a small allocation of gasoline for his very large car, and then paying exorbitant amounts for it. Late in that decade, the American President recommended turning down thermostats and donning sweaters to prepare for the “moral equivalent of war.” Heavy industry was hollowed out, and took many years to recover.

At the time, there were calls for a long-term energy strategy that would seek modest costs, security of providers and diversity of sources. Amid this year’s myriad energy shocks, it is clear that reconciling these aims is still a substantial challenge. My recent trips to oil producing areas in the Middle East and the United States underscored this point.

It is hardly of the scale of the 1973 embargo implemented by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), but last week’s announcement of oil production cuts will introduce discomfort to a range of nations. Inflation is at excessive levels, and falling gasoline prices were providing some relief. With oil prices higher by 15% already this month, that dividend is probably going to disappear.

Normally, higher prices are an invitation to additional production, but the ability of other suppliers to offset OPEC cuts is limited. Several nations with large reserves are the subject of international sanctions, and others have limitations caused by poor infrastructure. But the United States has also not been in a position to ramp up its output.

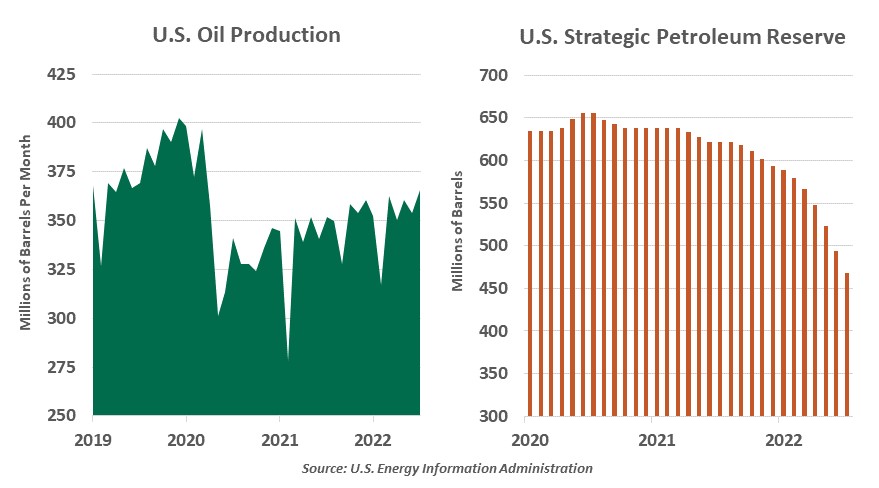

At one point prior to the pandemic, America had become the world’s leading source of petroleum. But since the onset of COVID-19, American production has lagged. We had thought that oil had become a “spigot business” where taps could be opened and closed with a minimum of fuss; that has not proven to be the case. Domestic daily output is still one million barrels per day lower than 2019 levels, despite prices that are above prior estimations of extraction costs.

Industry observers cite a number of drivers behind this development. There was an immense amount of money invested in energy exploration and extraction during the last decade, not all of it profitably. A number of energy firms did not survive the pandemic recession, and investors into the sector became more focused on returns. Capital for new projects is harder to get, and expected rates of return have risen.

American oil production has not risen to take advantage of higher prices.

Labor is also a significant constraint. The recession drove workers out of the sector, and many of them have not returned. Securing the human resources to reopen wells has been a tall and expensive order.

Even if additional crude can be extracted, it is unclear whether it could be processed. U.S. refining capacity is lower than it was prior to the pandemic, and it is fully employed. Several facilities were taken out of service in 2020, and they have not been replaced. In fact, the United States has not completed a new refinery since the late 1970s.

This is bad on the surface, but worse when you consider that newer facilities could handle higher volumes more efficiently and safely. Further, the bulk of U.S. refining capacity resides in an alley north of the Gulf of Mexico which is particularly vulnerable to severe weather. Unfortunately, communities are generally unenthusiastic about having a new refinery constructed close by.

A number of energy industry participants also feel aggrieved at the reputation that they have acquired. Some investors don’t want their securities in their portfolios; some job candidates don’t want their names on their resumes. The current administration has certainly focused more on climate change than the one that preceded it; the recently-passed Inflation Reduction Act includes a wide range of measures and incentives that aim to control carbon.

Those in the energy sector offer that their companies are conducting important research into ways that traditional fuels can be used more efficiently and cleanly. And even under reasonably aggressive transitions to sustainable fuels, we will be needing oil and natural gas in important amounts for some time to come. Securing sufficient supply at a reasonable cost will require continued investment. As one client told me: we need an “all of the above” energy strategy.

For now, though, production remains impaired. To prevent prices from increasing even more severely, the U.S. government has been releasing about one million barrels a day from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The SPR is now down to a nearly 40-year low, however, and will need to be replenished.

This lack of an American production response may be one reason that Middle Eastern sources thought the time was right to extract additional rent. The action has angered the Biden Administration, which has vowed to retaliate. Any response will have to be carefully calculated, though; the U.S. does not have a great deal of leverage to employ.

Rising oil prices won’t help the inflation picture.

Renewed increases in energy prices come at a bad time in the battle against inflation, which remains more than 8% over the past 12 months. Further, while central banks often choose to focus on “core” inflation (which excludes food and energy), research shows that energy prices are very influential in the way that consumers form inflation expectations, which the Fed is trying to contain.

To be fair, we have made significant progress over the past 50 years to reduce our reliance on imported oil. Manufacturing is less energy intensive, and cars have generally become more fuel efficient. But the moral and economic battles to become more self-sufficient are still going on.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Carl R. Tannenbaum

Carl R. Tannenbaum

Executive Vice President and Chief Economist

Carl Tannenbaum is the Chief Economist for Northern Trust. In this role, he briefs clients and colleagues on the economy and business conditions, prepares the bank's official economic outlook and participates in forecast surveys. He is a member of Northern Trust's investment policy committee, its capital committee, and its asset/liability management committee.