by Vaibhav Tandon, Senior Economist, Northern Trust

The pandemic surge in demand for houses has run its course.

The global economy, already contending with a host of issues ranging from raging inflation to the Ukraine war, is facing yet another uncertainty: the unraveling of a pandemic-induced housing boom. Red-hot markets are turning cold from Toronto to Auckland. Amid rapid deterioration in affordability, home sales are faltering, and prices are dropping sharply.

Home sales have fallen from their pandemic peaks by around 45% in New Zealand, 40% in Canada and Britain, 30% in the U.S. and 25% in Australia. House values are moving in a similar direction, declining about 10% from the pandemic peak in New Zealand, 6% in Canada and about 5% in Australia. Though still elevated, price growth in the U.S. has decelerated for four months in a row. Europe hasn’t been immune. Home price growth has slowed sharply in Germany, with the U.K. also showing signs of cooling.

House prices got a substantial lift from ultra-accommodative pandemic policies. Generous economic stimuli and sector specific measures, such as the stamp duty holiday in the U.K., helped buyers amass down payments. Home loans became more affordable as monetary policy depressed the costs of servicing mortgages. The search for larger spaces to accommodate working from home has been another force driving demand. Inflating construction costs and scarce inventories hindered building, contributing further to the rise in home values.

However, mortgage rates have spiked sharply since the start of the year in major markets. Given the enduring battle against inflation, rates are going to rise further. Borrowing costs for households have surged, and will continue to do so.

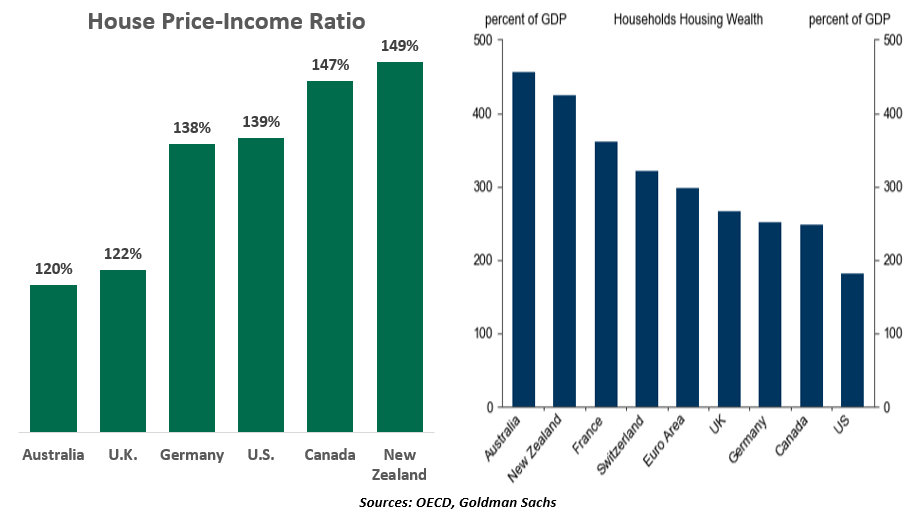

All of this has raised concerns of a housing crash. Home price-to-rent and price-to-income ratios in many large countries are higher than they were before the 2008 financial crisis, a sign that prices have moved disproportionately to fundamentals. New Zealand, Australia and Canada are particularly vulnerable to falling prices, as they have the biggest apparent imbalances. In addition, the households in two of three above markets are also among the most heavily indebted.

Housing is a key area of the economy, with a multiplier effect on activity. A slowdown in the sector will dampen growth through lower residential investment. A sustained drop in home values will also erode wealth, dent consumer confidence and impair bank lending as the risk of bad loans rises.

Australians and New Zealanders would suffer the most, as housing wealth exceeds 400% of gross domestic product (compared to under 200% in the U.S.).

Decelerating house prices offer some hope of slowing inflation, but the effect will take time to play out. The pass through will be swifter for nations like New Zealand, Australia, Canada and Sweden where shelter inflation is partly based on home prices. But is unlikely to bring immediate relief in most parts of Europe and the U.S. The inflation gauges tracked by the European Central Bank and the Bank of England do not include owner-occupiers’ housing costs. In the U.S. consumer price index calculation, shelter inflation is based on rental prices (or the equivalent rent an owner would pay) and not directly on home values.

A housing correction is underway, but a crash is unlikely.

After two years of strong growth, the housing market is finally running out of steam, but a 2008-style collapse remains unlikely in most places. Affordability stress tests, introduced in the aftermath of the previous crisis, have curbed uncontrolled lending in major markets like the U.S. and the U.K. Banks in Australia have already started to tighten lending standards. Household balance sheets are still strong in most of Europe and the U.S. A high proportion of fixed rate mortgages in Europe and in the United States will continue to protect borrowers from the impact of rising rates.

Nevertheless, rising interest rates, high valuations and falling real incomes present quite a challenging landscape for housing markets. The risk is that a simple chill could turn into a deeper freeze.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Vaibhav Tandon

Vaibhav Tandon

Vice President, Economist

Vaibhav Tandon is an Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Vaibhav briefs clients and colleagues on the economy and business conditions, supports internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishes the bank's formal economic viewpoint. He publishes weekly economic commentaries and monthly global outlooks.

Copyright © Northern Trust