by Robert Waldner, Chief Strategist and Head of Macro Research, Invesco Fixed Income

Key takeaways

U.S. inflation pressure may be easing - The message from market-based indicators and core inflation data is that the worst of the inflationary pressure may be behind us.

Is a U.S. policy error ahead? - If the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) continues to tighten well after inflation pressure has eased, this could be a policy error with very serious consequences.

The world is watching - As the central bank of the reserve currency, the Fed could pressure the entire global system if it tightens too much.

Global developed market central banks have been clear that they are laser focused on inflation. Indeed, U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell recently said that the biggest risk facing the Fed is failing to restore price stability and that the Fed is strongly committed to using its tools to cool prices. The impression we are left with is that the Fed has completely bought into the current zeitgeist that the singular threat to the global economy is inflation. Furthermore, Powell has stated that the Fed will continue to raise rates until it gets clear and convincing evidence that inflation is declining. There is a risk that Powell and other central banks’ focus on inflation could lead the global economy into recession and increase the risk of a financial accident.

Slowing growth

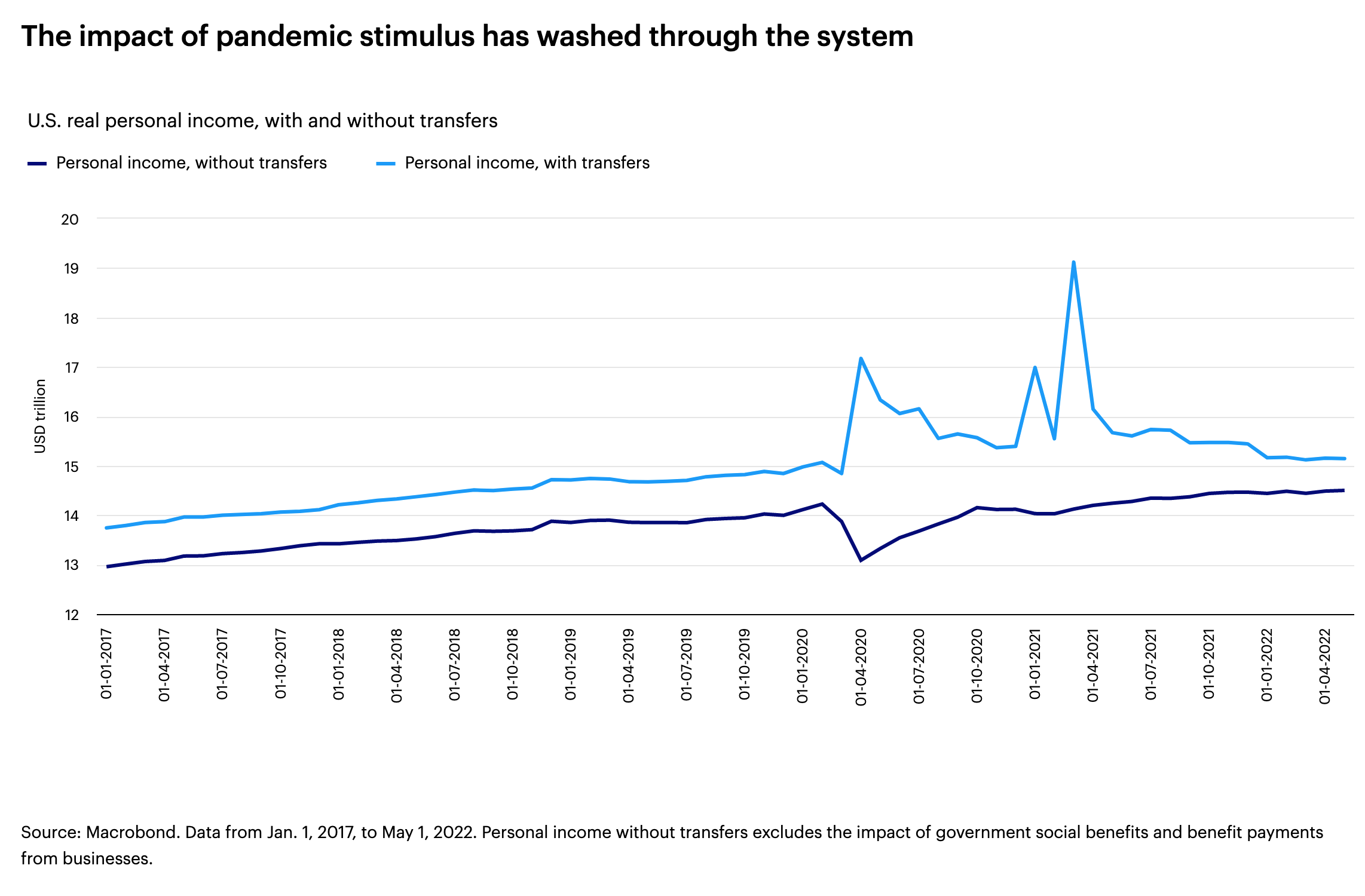

We know that growth is slowing, and that Western economies are coming off a massive, policy-driven boom. The light blue line below illustrates that U.S. personal income (Figure 1) boomed during the pandemic as the government implemented multiple rounds of direct stimulus. (The dark blue line illustrates personal incomes without the impact of stimulus and other transfers.) This has now washed through the system, and indeed, real income growth is currently negative, as wages have not kept up with inflation. This is a headwind for consumption and growth going forward.

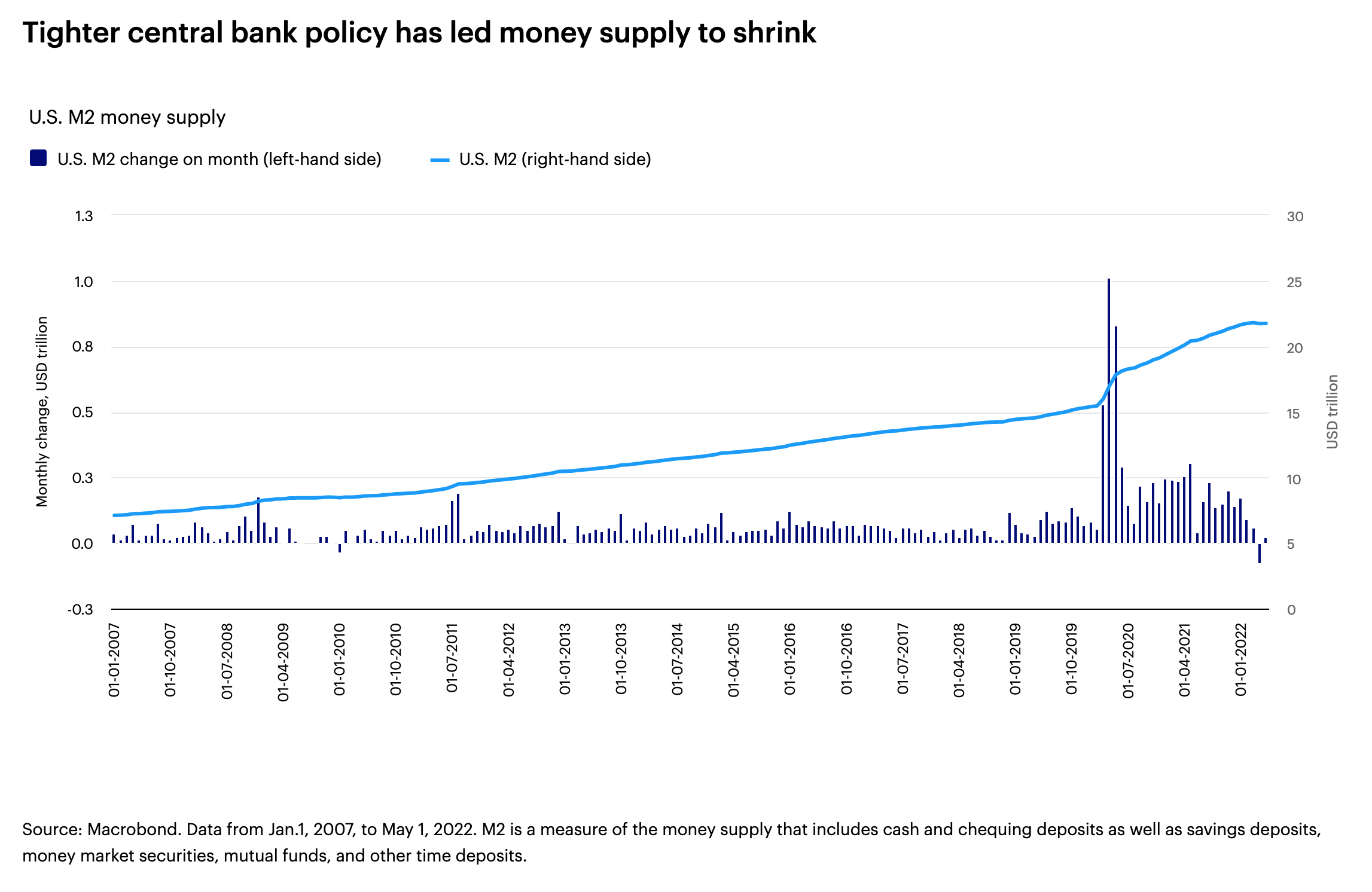

Monetary policy also aggressively and unprecedentedly boosted the global economy during the pandemic. The combination of aggressive rate cuts and quantitative easing boosted money supply and liquidity. As central banks have transitioned to tighter policy in recent months, this support has also dried up. Interest rates have been rising and central bank balance sheets are beginning to shrink. U.S. money supply growth has slowed, and the U.S. M2 money supply actually shrank in April (Figure 2), which is a rare and concerning event.

On top of this, there is a risk that a more abrupt slowdown in U.S. growth may be in process sooner than expected. Real time growth indicators, such as Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) data, have begun to decline; anecdotal evidence of inventory buildup and slowing goods demand is increasingly common. As for gross domestic product (GDP), real GDP decreased at an annual rate of 0.9% in the second quarter of 2022, following a decrease of 1.6% in the first quarter.1 It may be debatable whether the U.S. is in a full recession, but recent data show that the economy is slowing.

U.S. inflation pressure may be easing

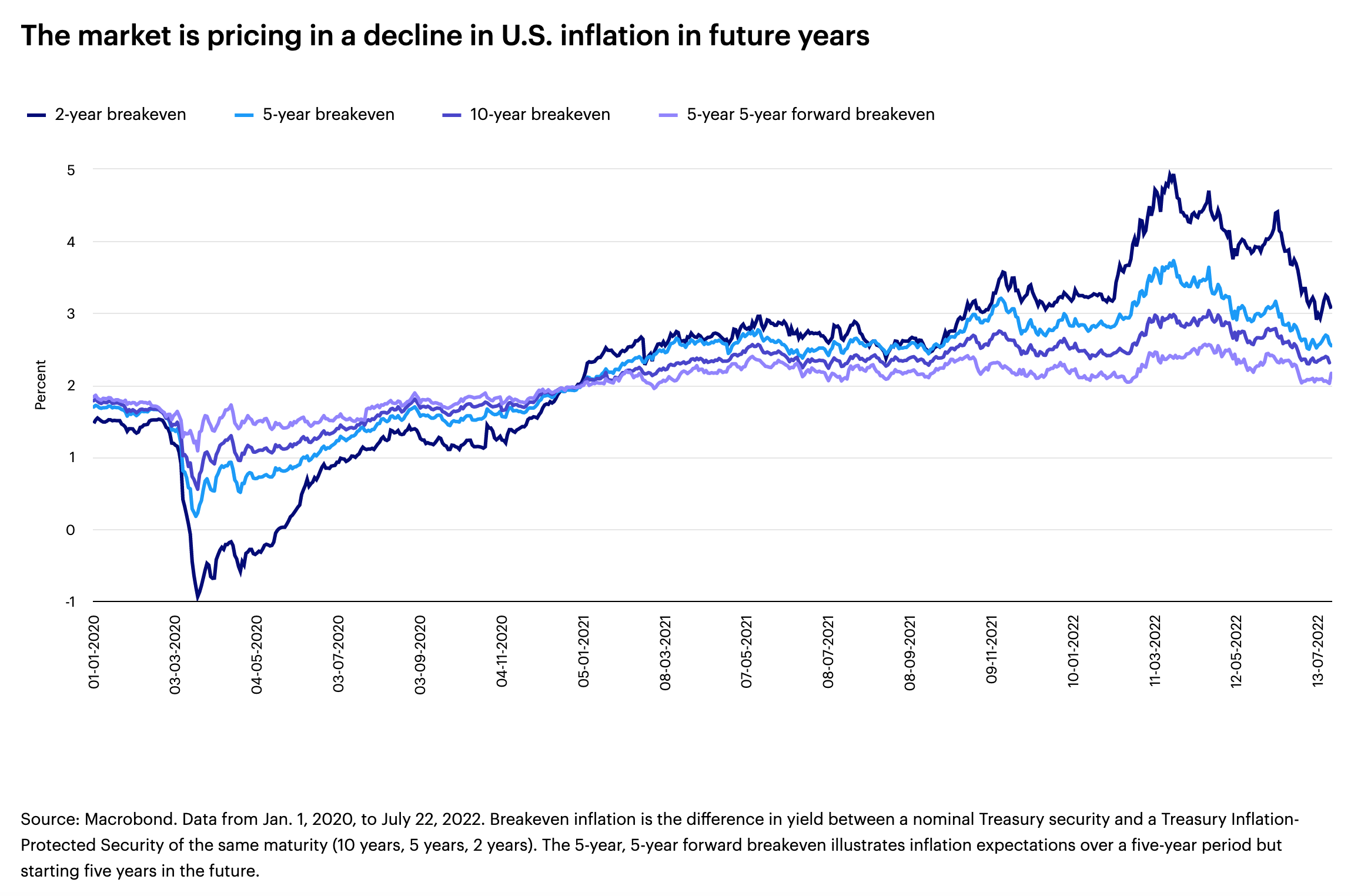

Inflation, which has attracted the attention of the central banks, is very high. Headline inflation is over 8% in both the U.S. and the eurozone, boosted by the sharp rise in commodity and energy prices.2 There are signs, however, that some inflationary pressure is easing. U.S. core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, appears to now be on a downward track on a year-over-year basis. Market-based estimates of inflation expectations derived from the inflation-adjusted bond market have been declining for several months in the U.S. (Figure 3).

So, the message from the market and core inflation is that the worst of the U.S. inflationary pressure may be behind us. The stimulus-driven demand push and supply chain issues may be easing, and that may allow inflation to decline going forward. In other words, the policy-driven bump up in prices may be passing through the system and prices may ease to their pre-pandemic dynamics.

The potential policy mistake

Today’s high inflation is the overwhelming priority for Western central banks, and we believe they are looking for clear and convincing evidence that inflation is declining before they stop tightening monetary policy. In my view, this is a problem. Central banks are watching a lagging indicator, or in the case of survey-based inflation expectations, a moving average of a lagging indicator, to set monetary policy.

The problem is, we know that monetary policy is forward-looking and works with long and variable lags. Setting a forward-looking policy based on lagging data is akin to driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror – prone to serious error. If the Fed continues to tighten well after inflation pressure has eased, this could be a policy error with very serious consequences, and it may not be corrected until a crisis arrives.

As the central bank of the reserve currency, the Fed’s actions are particularly important for the global economy. If the Fed tightens too much, it could pressure the entire global system. We have a long history of such accidents being accelerated or precipitated by a tightening Fed. We had the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, The Asian crisis of 1997, and the Russian and Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund crises both in 1998. In 2007, we had the U.S. housing crisis, which eventually made its way to the euro crisis of 2011, which was solved by extraordinary action by the European Central Bank (ECB). A policy mistake by the Fed now could precipitate another crisis — the question is, which one?

Global vulnerabilities

A tightening Fed would likely reduce global liquidity — which would be a headwind for many global markets. While emerging market countries are usually particularly vulnerable to reduced liquidity and associated funding stresses, Europe looks quite vulnerable this cycle. The ECB will likely have to raise interest rates to combat inflationary pressure, but at the same time manage the risk that funding dries up for the peripheral European countries, so-called “fragmentation risk.” The ECB is announcing tools that will hopefully help to manage these two potentially competing aims, but the efficacy of these policies is unknown, and the risks of a mistake are real. Managing this tricky trade-off will likely be more difficult with global liquidity tightening led by the Fed.

The bottom line is that a Fed policy mistake is possible, and I believe it would likely be very disruptive for global markets. While it is hard to predict with certainty, the eurozone looks vulnerable to such a disruption during this cycle.

Footnotes

- 1 Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data as of July 28, 2022.

- 2 Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of July 13, 2022. Eurostat, as of July 1, 2022.