by Tristan Sones, CFA® Tom Nakamura, CFA®, AGF Management Ltd.

Beyond its devastating human toll, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has had ripple effects around the world. For Western consumers and businesses, perhaps the most noticeable of those has come in the form of soaring gasoline prices (they have reached all-time highs in Canada and elsewhere), and financial headlines are dominated by talk of a new energy crisis brought on by the increasing economic isolation of Russia, which produces about 10% of the world’s oil. Yet although energy prices are certainly contributing to inflation globally, another Ukraine-created shortage is also brewing – in food. In fact, the global food supply crunch and resulting higher food prices could well provide a larger and longer-lasting tailwind to inflation than energy will. As the next few months or even years unfold, food inflation is likely to have an outsized impact on Emerging Markets (EM), but that impact will probably not be uniform. There will be countries that benefit and others that are adversely affected – and that could have meaningful ramifications for EM fixed income investors.

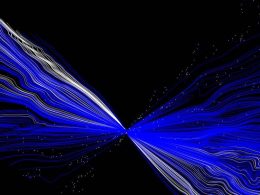

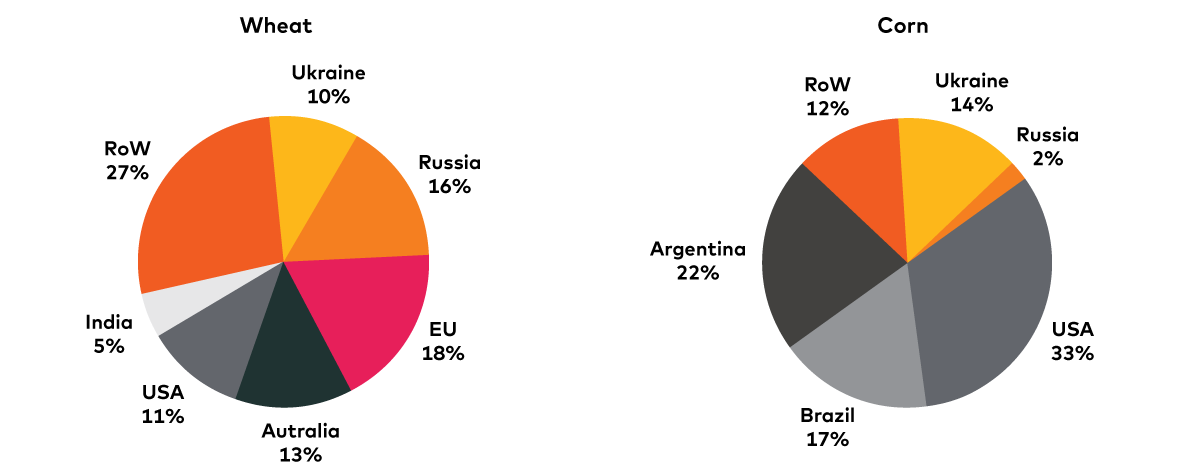

Before this year, Russia and Ukraine accounted for more than a quarter of global wheat exports and more than 15% of corn exports; the war in Ukraine has effectively removed two of the largest exporters of those critical grains from global supply chains. The conflict is also creating shortages of fertilizer, possibly suppressing crop yields and adding to farmers’ input costs at a time when fertilizer prices were already very high. Those factors have had a clear impact on prices: wheat futures soared by more than 40% in the immediate wake of Russia’s invasion, and corn futures remain nearly 20% higher than they were in mid-February, Bloomberg data shows. It might take some time until these increases are substantially passed through to consumers, but if history is our guide, the food shock could well be a greater contributor to inflation, both in degree and in duration, than the oil shock. (See charts below.)

Food Inflation and Emerging Markets

Source: HSBC, More Complications for EM, March 16, 2022

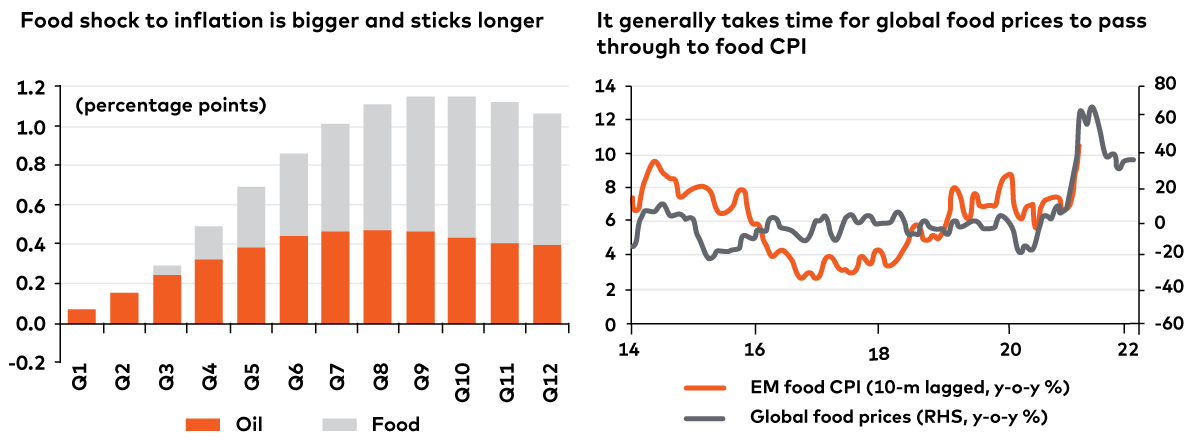

On average, EMs are more vulnerable to food inflation, simply because food comprises a greater proportion of consumers’ expenses. In many Emerging Markets, food accounts for more than 40% of overall consumer expenditures; in the U.S. and Canada, it accounts for less than 10%, according to the World Economic Forum. As a result, consumer prices in EMs are generally more sensitive to food inflation than to energy inflation, and that is contributing to above-trend price increases overall. (See charts below.)

Consumer Price Indices (CPI) Weights

Source: Credit Suisse, Emerging Market Quarterly: Q2 2022, April 5, 2022

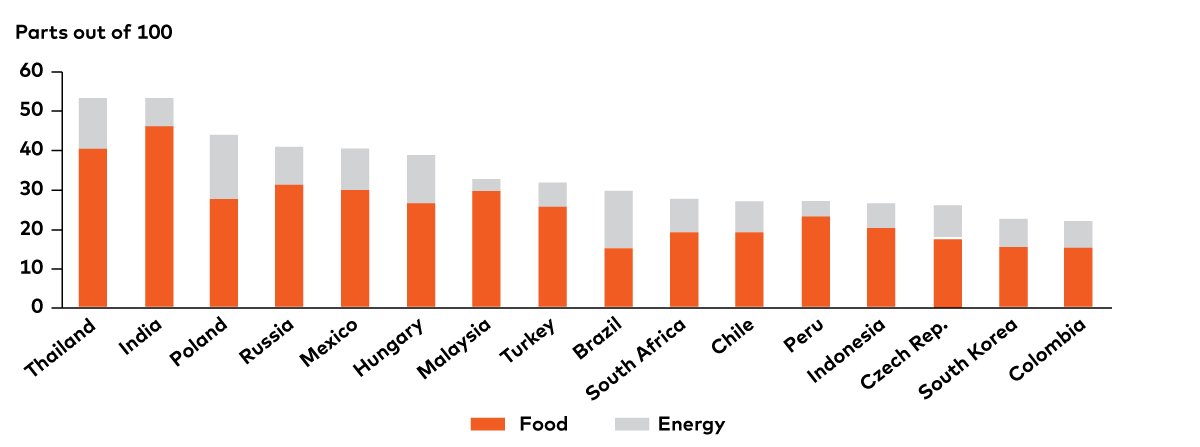

Global Inflation, Inflation in EMs, EMs ex-China and DMs (%, year-on-year change)

Source: Credit Suisse, Emerging Market Quarterly: Q2 2022, April 5, 2022

For many EMs, rising food prices might pose difficult economic and social challenges. Several were already grappling with resurgent inflation last year as they began to emerge from the restrictions and economic headwinds of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some central banks, such as Brazil’s, Mexico’s, the Czech Republic’s and Hungary’s, got out ahead of their developed-market counterparts in raising rates. In fact, the benchmark interest rates for just 11 EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) and Latin American markets rose by a total of more than 4,000 basis points since the middle of 2021, according to UBS Investment Bank. Now, however, war in Ukraine has amplified inflationary pressures, and EM monetary policymakers might have little choice but to raise rates further or, at best, delay moves to moderate them. In Egypt – a net food and energy importer – the central bank had not raised rates since 2017, but did so by 100 basis points in March, citing the war in Ukraine as one inflationary factor.

Meanwhile, rising food prices (and shortages) have contributed to social unrest in Sri Lanka, where food inflation soared past 30% in March, Reuters notes, and in Pakistan, where it is running in the double digits, according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. For fixed income investors, such civil strife could raise the political risk attached to EM debt. And if consumer dissatisfaction with paying more for the necessities of life continues to grow, some EM governments might go down (or further down) the well-worn fiscal path of subsidization, income supports or export controls. That could have the effect of aggravating fiscal deficits, undermining currencies and forcing governments to issue more debt, putting further upward pressure on yields even as central banks are raising rates.

Clearly, then, there are downside risks, but the picture is not all dark. Indeed, several EMs may stand to benefit from rising food prices. For example, Argentina and Brazil stand out among Emerging Markets as significant exporters of corn, with 22% and 17% of global export share, respectively. India, meanwhile, is the world’s seventh-largest exporter of wheat, according to Citigroup. Its fiscal year ending in March set new records for wheat exports; the industry is now looking to expand its export markets and expects a bumper crop for the 2022 harvest, according to Reuters.

Global Gross Exporters, 2021/22

Source: CitiGroup, Emerging Markets Strategy Weekly, April 7, 2022

For these big grain producers, high commodity prices and increased exports could help dampen the impacts of inflation by improving terms of trade, supporting local currencies and granting governments more fiscal room to address rising prices in other areas, like energy. To that extent, their central banks might be less motivated to raise rates (or, at least, to raise rates as much as they otherwise would have). As well, to the extent they can fill the gap created by the war in Ukraine, these exporters may help other EMs better address food shortages and rising prices, particularly within their respective regions. India, for example, ships wheat to Bangladesh, Oman, Qatar, Sri Lanka and South Korea, Reuters reports.

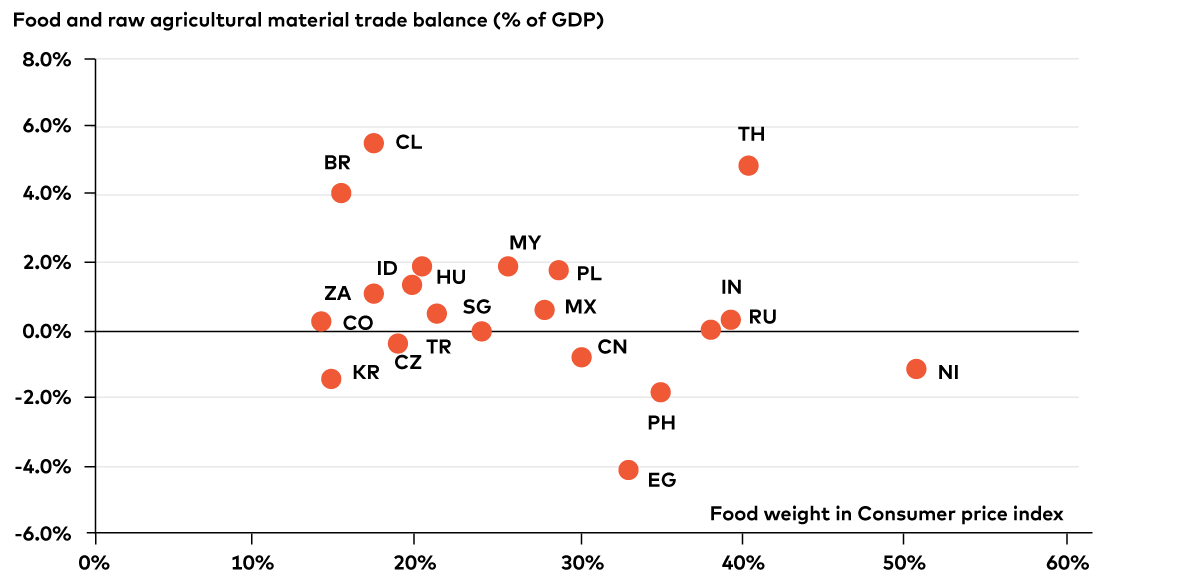

Even here, however, the EM landscape presents grey areas, and when we cross reference the two factors discussed above – food’s share of CPI and export position – a more complex picture emerges:

Agriculture Trade Balance versus Food Weight in Domestic CPI Baskets

Source: UBS, Spillovers from Russia/Ukraine to broader EM in 10 Charts, February 25, 2022

The sweet spot in the above chart is the upper-left quadrant, where countries enjoy a positive agricultural trade balance and a lower food weight in CPI. Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Colombia, Hungary and South Africa are among the potential food-inflation “winners,” and we can anticipate rising food prices will provide a benefit to their trade balances and fiscal positions. Other markets – for instance, large rice producers – might be able to tap into demand for wheat and corn substitutes, and large rice importers might be cushioned against higher inflation, at least to some extent.

Meanwhile, India and Thailand have positive agriculture export positions, but food eats up a large share of consumers’ incomes; that might motivate monetary policymakers in these countries to tilt toward hawkishness in the face of rising food prices in the coming months. In contrast, South Korea is a net importer, but food accounts for a relatively small portion of CPI, which should mitigate the economic impact of inflation. The most clearly negative outliers are China, Egypt, the Philippines and Nigeria, which are net food importers where food comprises a large share of CPI; we would expect food inflation to have a more significant impact on central bank policy in these markets.

For such food-importing countries, the challenge will be to address inflationary pressures without inflicting long-term damage on their economy and credit quality. On the monetary side, central bankers may seek to maintain credibility on inflation and help stabilize their currencies by raising rates, but that creates a downside risk of slowing, negating or reversing economic growth. Meanwhile, government efforts to subsidize food or raise incomes might prove popular, but too much fiscal support could create the potential for credit downgrades and questions among global investors over debt sustainability. Striking the right policy balance may prove to be a complicated dance.

On the other hand, for food exporters, higher prices should support growth and the ability to service debt, improving their credit profile. If food inflation provides a sufficient economic tailwind, these countries might even opt to come to market with new bond supply. Their central banks may also be less aggressively hawkish on the policy front, all else being equal. Of course, “all else” is rarely equal. Food inflation is not occurring in a vacuum. Rising prices in materials and energy may counterbalance any benefits, even for food exporters.

That’s one reason why EM fixed income investors would do well to bear in mind that not all Emerging Markets are the same. Each has its own idiosyncrasies and complexities. Those might be especially important realities to recall when laying bets on the risks and opportunities that food inflation will create.

Tristan Sones is Vice-President and Portfolio Manager, Co-Head of Fixed Income at AGF Investments Inc. He is a regular contributor to AGF Perspectives.

Tom Nakamura is Vice President and Portfolio Manager, Currency Strategy and Co-Head of Fixed Income at AGF Investments Inc. He is a regular contributor to AGF Perspectives.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of AGF, its subsidiaries or any of its affiliated companies, funds, or investment strategies.

The commentaries contained herein are provided as a general source of information based on information available as of May 10, 2022, and are not intended to be comprehensive investment advice applicable to the circumstances of the individual. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication, however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Market conditions may change and AGF Investments accepts no responsibility for individual investment decisions arising from the use or reliance on the information contained here.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA), AGF Investments LLC (AGFUS) and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA). AGFA and AGFUS are registered advisors in the U.S. AGFI is registered as a portfolio manager across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.

® The “AGF” logo is a registered trademark of AGF Management Limited and used under licence.

RO:20220511-2195624

About AGF Management Limited

Founded in 1957, AGF Management Limited (AGF) is an independent and globally diverse asset management firm. AGF brings a disciplined approach to delivering excellence in investment management through its fundamental, quantitative, alternative and high-net-worth businesses focused on providing an exceptional client experience. AGF’s suite of investment solutions extends globally to a wide range of clients, from financial advisors and individual investors to institutional investors including pension plans, corporate plans, sovereign wealth funds and endowments and foundations.

For further information, please visit AGF.com.

© 2022 AGF Management Limited. All rights reserved.

This post was first published at the AGF Perspectives Blog.