by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Franklin Templeton Investments

I used to live in London in an earlier phase of my professional career. I loved London, and still do, for many reasons—bear with me, I promise this will bring us back to the Federal Reserve (Fed). One thing I did not love as much was the frequent delays on the tube—the subway train system. During the fall, the public system announcement would often explain that the trains were running very late due to…leaves on the tracks. This was met with polite surprise, as falling leaves in autumn could hardly be considered an unexpected phenomenon. Investigative journalism eventually revealed that yes, falling leaves in autumn had been anticipated, but those that fell on the tracks were the wrong kind of leaves.

I thought of this when Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said at the latest Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) press conference: “the inflation we got is not at all the inflation we were looking for”.

Much like the leaves on London’s train tracks, this announcement has generated amused puzzlement and a measure of sarcasm. And much like in the case of London’s leaves, it is useful to understand what went wrong.

As Powell explained it, the Fed hoped that above-target inflation would eventually result from running the economy too hot for some time, above full employment levels. Instead, inflation has soared to nearly 7% before full employment has even been reached, in the Fed’s view. Blame supply chain disruptions, the “wrong kind of leaves” that have suddenly blocked the smooth transiting of goods and caused an unexpected surge in prices. Unforeseeable, and certainly not the Fed’s fault, right?

But just like London’s wrong kind of leaves, this sounds a lot more like an excuse than an explanation.

Yes, global supply chains suffered a sudden shock. But when early last year the global economy shut down and countries started imposing arbitrary and ever-changing restrictions on travel, transportation and business activity, a curious mind could have guessed this would impact supply. The fact that extraordinarily loose monetary policy, combined with a rebound in pent-up demand, a massive fiscal expansion and supply restrictions would result in higher prices should not have come as such a surprise.

You can call it the wrong kind of inflation, but every time that demand greatly outstrips supply, inflation is what you get. Much like in autumn you get falling leaves.

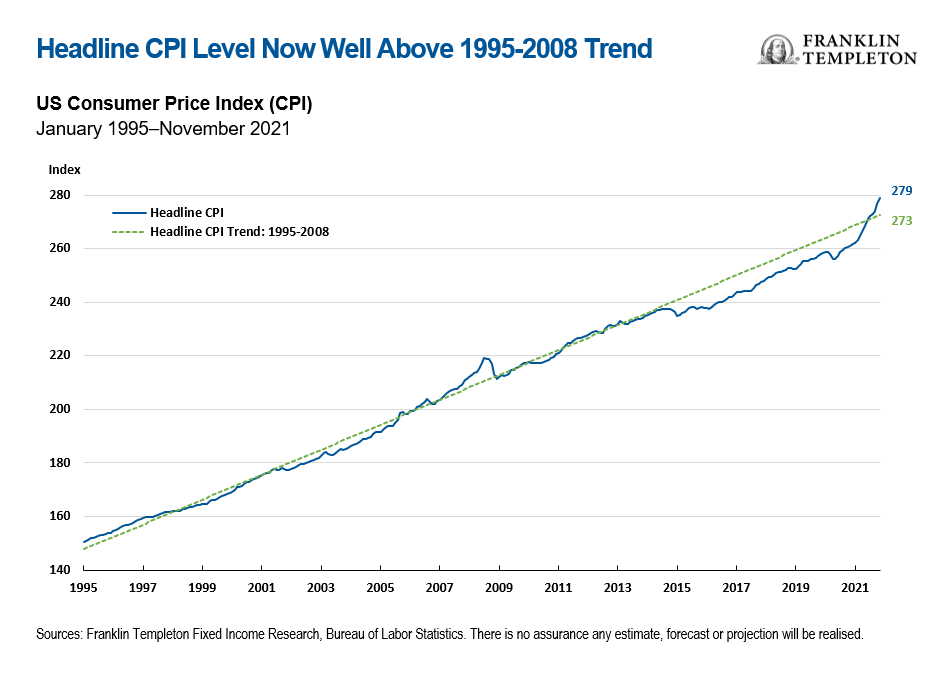

I do believe Powell is sincere when he says, “this is not all the inflation we were looking for”. The Fed was probably hoping to get 3%-4% year-over-year (Y/Y) inflation for an extended period, slowly making up for past inflation undershoots, with strong growth, rising employment and rising real wages. Instead, inflation shot up, and we have already more than made up for the low-ish inflation of the past 15 years. The headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) is now above the 1995-2008 trendline; we are in straight overshooting territory (see chart below). Nominal wages have lagged behind prices and if/when they try to catch up it will make high inflation more persistent. And the longer high inflation persists, the deeper it gets embedded into inflation expectations, making the problem harder still.

The Fed may not have gotten what it wanted, but I think it might have gotten what it needed—for a reality check.

This “wrong kind of inflation” is the direct result of the Fed’s endlessly loose policy stance, combined with a similarly loose fiscal stance. And yet the Fed seems to have been caught by surprise by its own policy: as late as September, half of the FOMC members did not see any reason to hike rates in 2022; as late as last month they still characterised inflation as “transitory”. Now they all acknowledge rate hikes will be needed, and have decided to double the pace at which they are tapering asset purchases.

The December FOMC has been saluted as a major hawkish pivot. But the reality is that with an overheating economy and inflation at multi-decade highs, the Fed will continue to expand its balance sheet and keep interest rates at zero for several more months—and it expects to keep real interest rates negative for the whole of next year at least. Some might call it “the wrong kind of hawkish pivot”…

The Fed needs to move carefully because it has put itself in a very difficult position: it needs to tighten policy fast enough to prevent high inflation from getting entrenched; but if it tightens too fast it might disrupt financial markets that have gotten too dependent on its liquidity support.

It would be helpful to recognise that the basic laws of economics still hold: excessively loose policy eventually causes demand to exceed supply, and that creates inflation. No need to worry about exactly what kind of leaves will fall on the tracks in autumn.

Investors now need to brace for higher volatility. The Fed has acknowledged it needs to react to high inflation and adjust its policy; this will limit its ability to support and stabilise asset prices, and markets will need to adjust and get used to it. On top of this, the economy remains subject to significant uncertainty: from developments in the COVID-19 pandemic to the way companies are adjusting to supply chain disruptions, to changes in economic policy around the world. It looks like 2022 is going to be another interesting and challenging year. In some ways, perhaps, not at all the kind of interesting we were looking for—but let’s try and make the best of it.

In early January, we will publish our new quarterly Franklin Templeton Fixed Income Views, with our updated strategy views and investment recommendations across fixed income sectors. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile,

Happy holidays!

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Investments in lower-rated bonds include higher risk of default and loss of principal. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value.

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realised. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Distributors, LLC, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com – Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

This post was first published at the official blog of Franklin Templeton Investments.