by Ryan James Boyle, Northern Trust

What is in the new infrastructure bill, and what's next for Congress?

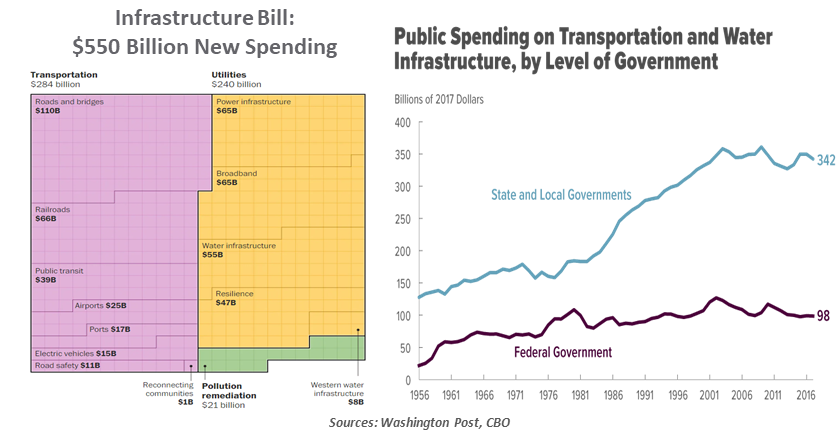

This month, following a year of speculation and months of legislative uncertainty, the U.S. passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, containing over $550 billion of new spending. Many of these investments are well-justified, but the spending likely won’t stop there.

We have written in the past about the political conundrum of infrastructure spending. Most politicians support investment in their districts, and the role of government in providing basic public services is not in question. Important details like identifying specific projects to be funded and how to pay for them derailed past proposals, but this year’s bill broke through to earn bipartisan support.

Surely some members of the Biden administration have taken to heart the struggles of the economic recovery under the Obama administration. Taking office amid a recession, Obama championed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion stimulus that included $105 billion for “shovel ready” infrastructure projects. However, major building projects require years of planning; the Recovery Act did little to get people back to work quickly. For this reason, Biden’s push for infrastructure was not positioned as economic relief, and this bill came after a final COVID relief act with a more immediate spending horizon.

Today’s circumstances are quite different than in 2009. The labor recovery from the COVID-19 recession continues. The greatest challenge now is finding workers to fill the plethora of open jobs. New public works will require labor and materials that are in short supply, to say nothing of the trucks and equipment needed on job sites. Spending is expected to take place over the next five years. Any lead time to start projects may be a benefit to allow time for the labor market recovery to continue; if shortages persist, government projects can be slowed or postponed with little economic loss.

The bill was advertised to be deficit-neutral, but that requires optimistic assumptions. Much of the funding came from reallocation of unspent COVID-19 relief funds. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the bill will add $256 billion to the deficit over the coming ten years. The CBO’s methodology considers only the government’s revenues and expenditures and does not consider the indirect benefits of enhanced infrastructure.

The bill makes important investments in a variety of public assets. Transportation leads the headlines. Roads and bridges, the mainstay of infrastructure negotiations, will receive $110 billion of additional funding. Railroads will see $66 billion, and public transit agencies an additional $39 billion, to move more people and goods without use of vehicles. The bill makes a limited push toward electrification, with $15 billion dedicated to expanding charging stations and electrifying fleets like school buses.

Infrastructure investment can pay dividends long after the projects are complete.

Utilities are also a focus, with $65 billion each for power and broadband networks as well as $55 billion for water management. The water funding includes $15 billion to remove residential lead water lines, a long-recognized health risk that is expensive to remediate. Funding for broadband is sometimes contentious, as most existing internet infrastructure is privately owned. However, last year’s lockdowns made broadband an essential service for employment, education and healthcare. Public investment to expand access to broadband will bring widespread public benefit.

More broadly, a more robust infrastructure can support productivity. Faster connectivity and movement of goods and people will allow everyone to make better uses of time. The supply crunch brought to light many inefficiencies in transportation networks, like the difficulty moving containers between ports and railyards. While we do not expect another COVID-like shock again, the problems that the crisis revealed should be fixed. And with labor supply still constrained and adverse demographics in the years ahead, every augmentation of worker productivity and international competitiveness will matter.

While this is a step forward for the president’s agenda, the work is far from complete. The federal government is currently funded with a continuing resolution through December 3, as Congress did not pass a budget in time for the start of the fiscal year on October 1. A shutdown looms unless the resolution is extended or a budget is passed; we believe an extension is likely. The debt ceiling returned as a constraint on the Treasury’s ability to issue debt this year. After a standoff in October, the limit was lifted only slightly. Estimates of the “x-date” at which the Treasury runs out of cash range from early December to as late as February; a more enduring solution is needed in short order.

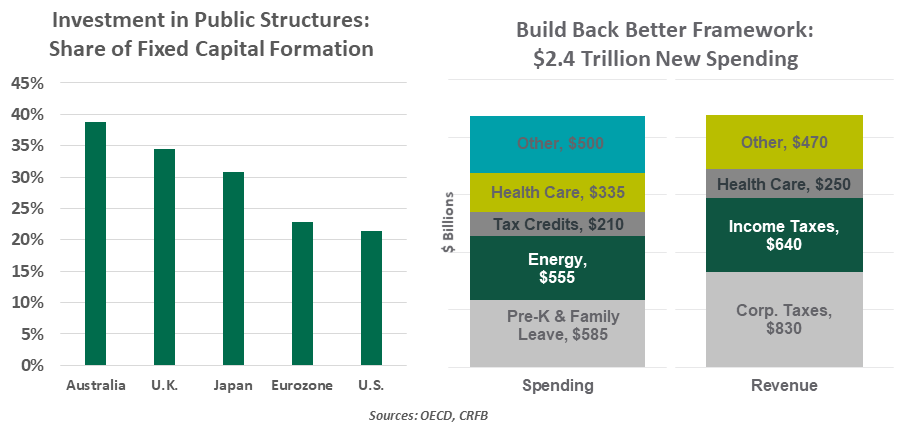

Negotiations surrounding the remainder of the Biden agenda are ongoing, with some of the more contentious discussions occurring within the president’s own party. The “Build Back Better” program of social spending has been pared back from its initial scale, with ideas like free community college and paid family leave falling out of the bill. With Democrats holding only 50 seats plus the tiebreaking vote in the Senate, every individual senator has veto power. Their willingness to continue to refine the bill suggests some additional spending is likely to pass.

Congress has urgent work to do to keep the country running.

Inflation worries have entered the fiscal deliberations. The skepticism is rational: why should the government spend more when the economy is already running hot? However, these proposals are not cash payouts that would further fuel consumer demand. Some of the programs remaining in the proposal are well-timed. For example, one cause of today’s labor crunch is a lack of childcare; more funding for care can help parents of young children return to work.

Policy has moved away from crisis response and toward long-term investment. Interest rates to finance these ambitions are modest. But there are still boundaries to be respected, and it will be up to the divided Congress to determine where those are.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Ryan James Boyle

Ryan James Boyle

Vice President, Senior Economist

Ryan James Boyle is a Vice President and Senior Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Ryan is responsible for briefing clients and partners on the economy and business conditions, supporting internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishing economic commentaries.