by Tom Nakamura, CFA® Tristan Sones, CFA®, AGF Management Ltd.

Insights and Market Perspectives

Author: Tom Nakamura

October 20, 2021

After months of speculation about when it would hit the brakes on quantitative easing (QE), the U.S. Federal Reserve made it clear after its September meeting that its US$120-billion-a-month bond-buying program would soon begin to wind down, perhaps as early as November. For investors in Emerging Markets (EM), this looming round of tapering might bring back some unpleasant memories. Back in May 2013, Fed chair Ben Bernanke threw global markets off-kilter by signalling a wind-down of the central bank’s post-Global Financial Crisis QE program. U.S. short-term interest rates skyrocketed, the U.S. dollar soared, and EM assets (equities, bonds and currencies) were hit especially hard. History is not always a good predictor of market behaviour, but it is still a legitimate question: Could the same thing happen to Emerging Markets this time around?

We suspect not. For one thing, the Fed has telegraphed its intentions for months now, and investors have largely not interpreted its signals as a dramatic change in direction that may significantly impact global liquidity conditions. Yet our relative confidence in Emerging Markets’ ability to withstand a U.S. QE wind-down goes beyond that. It also has to do with economic and financial conditions in EMs themselves. When we compare today’s environment to 2013, there are several good reasons to believe Emerging Markets will likely get through the Fed’s new taper without the tantrum, and that may have implications for investors’ EM fixed-income and currency exposures.

One important difference from 2013 is that EM bond yield curves are much steeper, almost across the board, based on our calculations using Bloomberg data. That is a function not only of continued concern over the lingering impact of COVID-19, but also of rising inflation expectations. As global growth and commodity prices have picked up, inflation in many EMs has been on the rise, to the extent that central banks are raising rates and bond markets are responding by pushing up long yields. This has created a dramatically different fixed-income environment from 2013. For example, the difference between two-year/10-year spreads in 2013 and today is more than 250 basis points in South Africa and Colombia, more than 100 basis points in Chile, and more than 70 basis points in Peru, Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia and South Korea, among others.

Steeper yield curves should help cushion those markets from higher short-term yields as the taper evolves. And while the risks in many EMs exist – not just inflation, but also the pandemic and in some cases credit concerns – those risks seem well recognized, and higher long yields are at least rewarding investors to taking on those risks. In the context of tapering, EM bond markets are on a more neutral footing than in 2013, when yield curves were largely much flatter.

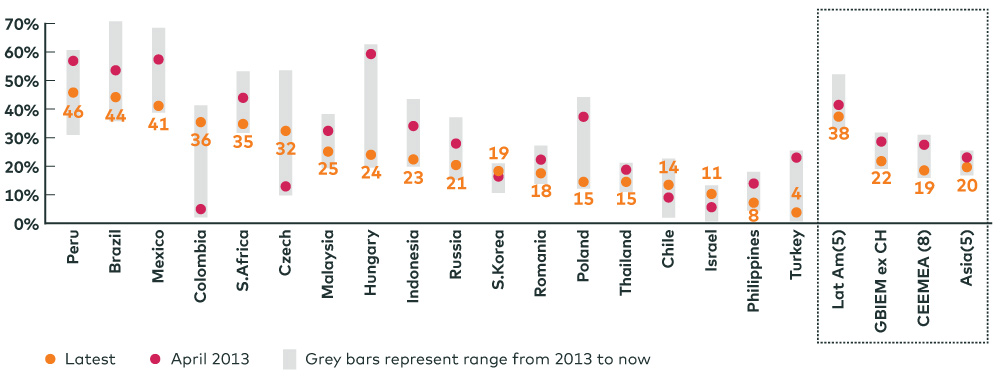

Another reason to be relatively buoyant about Emerging Markets is investor positioning. In 2013, foreign holdings of EM bonds were running high, as markets generally did not expect global liquidity to begin to dry up. (And we should point out that it largely did not dry up even when the Fed’s tapering began late in 2013.) Today, however, domestic ownership of bonds represents a much higher percentage of the total in many Emerging Markets, according to Deutsche Bank research. This suggests that should a global panic occur in the wake of Fed tapering à la 2013, it could have a significantly lower impact in many EMs, since there is simply a lower proportion of foreign investors and domestic investors are less likely to “flee” their home market. Hungary provides a stark example, where foreign ownership has declined to about 25% from about 60% in 2013. Closer to home, foreign investors’ share of Mexico’s bond market has declined by nearly 15 basis points. In short, foreign bond ownership drives Emerging Markets less than it used to, and “getting out” of EMs during a taper tantrum (should a tantrum even occur) would be a less crowded trade than it was eight years ago.

Non resident holdings of EM local currency bonds

Source: Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg Finance LP, CEIC, Haver, various government websites. Notes: The Asia and EM aggregates exclude China and Korea.

Finally, the U.S. dollar is already quite strong against EM currencies, which fell off a figurative cliff when COVID-19 fears peaked last spring and have since recovered only modest ground, Bloomberg data shows Prior to 2013, the USD had been in a devaluation cycle, which the taper tantrum promptly reversed. Today, the dollar is arguably on the expensive side, and further strengthening would hardly be an abrupt disruptive element in financial markets. As well, the current weakness in EM currencies suggests that there is no great appreciation that needs to be unwound, and markets may have already embedded quite a bit of concern about currency vulnerability (whether from tapering or the pandemic or some other risk). The Mexican peso in particular looks weak relative to 2013, on a trade-weighted, inflation-adjusted basis.

In our view, then, Emerging Markets are generally in better position to withstand a taper tantrum than they were in 2013. Yet even if concerns about the short-term impact of a QE wind-down can be laid to rest, a larger worry remains: the impact of tighter Fed policy on EMs. What happens, for instance, if the Fed and other large central banks might be taking inflation too casually and be forced to raise rates much more aggressively? And what if Emerging Markets get hit by another COVID-19 wave even as liquidity dries up?

Those are possibilities, of course, but the good news is that EMs are very unlikely to get both at the same time. While tightening can occur as the pandemic winds down, it seems unlikely to continue if the pandemic picks up, which would put central banks back on the sidelines. Meanwhile, the current account positions of many EM countries have improved significantly compared to 2013, according to HSBC research, which should soften the blow of currency depreciation and economic volatility (for a while, at least). We would also point out that EM currencies can do quite well in periods when yields are rising, as long as those increases are underpinned by strong global economic growth – which could well characterize the current environment, barring another pandemic setback.

So should investors put their fears of a tantrum to rest? Perhaps not entirely, but the bugbears of a taper tantrum – a mass exodus of foreign capital, radical currency depreciations and extreme volatility – seem like much lower-probability events today than in 2013. Accordingly, investors currently exposed to EM fixed income might wish to ride out any post-taper impact rather than reduce their exposures, or perhaps make a smaller adjustment than they otherwise might have. On the margins, there might be opportunities in steeper yield curves, which could provide roll-down capital appreciation as long EM bonds approach maturity. And the spectre of tighter Fed policy might not necessarily spook investors away from EM currencies, especially those that have already depreciated significantly.

Of course, the story is never simple in Emerging Markets. Each country has its own political, social and economic perils for investors. Yet, in the short term at least, those risks – and the Fed’s wind-down of QE – seem to be well priced-in by markets. In short, the next few months might turn out to be disruptive for EMs, but they are unlikely to be dramatic.

Tom Nakamura is Vice President and Portfolio Manager, Currency Strategy and Co-Head of Fixed Income at AGF Investments Inc. He is a regular contributor to AGF Perspectives.

Tristan Sones is Vice-President and Portfolio Manager, Co-Head of Fixed Income at AGF Investments Inc. He is a regular contributor to AGF Perspectives.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

To learn more about our fundamental capabilities, please click here.

The commentaries contained herein are provided as a general source of information based on information available as of October 12, 2021 and should not be considered as investment advice or an offer or solicitations to buy and/or sell securities. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication, however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Market conditions may change investment decisions arising from the use or reliance on the information contained herein. Investors are expected to obtain professional investment advice.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of AGF, its subsidiaries or any of its affiliated companies, funds or investment strategies.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA), AGF Investments LLC (AGFUS) and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA). AGFA and AGFUS are registered advisors in the U.S. AGFI is registered as a portfolio manager across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.

® The “AGF” logo is a registered trademark of AGF Management Limited and used under licence.

About AGF Management Limited

Founded in 1957, AGF Management Limited (AGF) is an independent and globally diverse asset management firm. AGF brings a disciplined approach to delivering excellence in investment management through its fundamental, quantitative, alternative and high-net-worth businesses focused on providing an exceptional client experience. AGF’s suite of investment solutions extends globally to a wide range of clients, from financial advisors and individual investors to institutional investors including pension plans, corporate plans, sovereign wealth funds and endowments and foundations.

For further information, please visit AGF.com.

© 2021 AGF Management Limited. All rights reserved.

This post was first published at the AGF Perspectives Blog.