by Adriaan du Toit, Senior Economist, Africa, AllianceBernstein

COVID-19 has increased inequality and aggravated social problems across emerging market economies, fueling populist pressures—but several emerging countries share features that make them particularly vulnerable. Assessing key environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics can help identify potential pressure points.

Crisis can be fertile ground for populism. The unique characteristics of COVID-19 may have stifled unrest initially, but the pandemic has exacerbated inequality and poverty, which could fuel public discontent, impacting political and policy paths. It has also given a double edge to the youthful nature of many emerging countries. A young demographic profile is normally a positive for economic growth, but could pose challenges if the pandemic curtails business activity and permanently increases unemployment.

Political and policy shifts are arguably more likely in countries where socioeconomic conditions are more fragile and where COVID-19 scarring is deeper. But the resulting pressure for change could lead to contagion, pushing politicians across emerging markets to pursue populist policies, delay fiscal consolidation, and/or erode democratic standards.

ESG Considerations Are Vital to Understanding Political and Policy Risks

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected income, health and education across emerging markets. Lower-skilled workers have been most affected, and poverty has increased substantially in low-income countries with weak social safety nets. When we evaluate sovereign bonds, we apply an ESG framework that accounts for wide-ranging factors, including these negative development impacts.

Of all emerging regions, we think Africa has been hardest hit in terms of human development and equality. Africa’s young demographic profile probably reduced the incidence of COVID-19 deaths, but potential economic growth could be diluted if the pandemic undermines human development indefinitely. Viewed through this lens, Africa is at greatest risk of political and policy shifts due to potential COVID-19 scarring. But quite a few emerging markets in Asia and Latin America have comparable demographic and income inequality dynamics, and therefore face similar risks (Display, below).

Economic Populism Directly Impacts Policy

Economic populism typically features the prioritization of growth and income redistribution, while addressing fiscal and inflation risks takes a back seat. Because the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated inequality and poverty, economic populism could rise and/or democratic principles could degrade. If emerging-market economic growth disappoints and incomes and employment remain depressed, populist policy options could gain traction. These include social security expansion, a higher debt threshold and burden sharing between central banks and governments (fiscal dominance).

Africa Most Exposed to COVID-19 Aftershock

In Africa, where poverty and inequality are particularly pronounced, the political ground has already started shifting, including leadership changes and civil unrest.

In the North, Tunisia’s President Saied dismissed the government, suspended parliament, and transferred all powers to the presidency. In South Africa, President Ramaphosa responded to unprecedented civil unrest by reshuffling his cabinet, in the process giving himself direct oversight and control over intelligence gathering and operations. Saied and Ramaphosa are champions of anticorruption and are popular among voters. But public discontent has intensified during the pandemic, and the tables could turn on the two leaders if economic recovery is delayed.

Such a reversal occurred unexpectedly in Zambia last month with opposition party leader Hakainde Hichilema’s landslide defeat of President Lungu. Zambia’s economy was faltering long before the pandemic, but COVID-19 brought added pressure, and the country defaulted on its eurobonds in 2020. The government’s obstructive and opaque policies also ruled out meaningful multilateral assistance, worsening the crisis. The power of incumbency was still expected to tilt the scales in Lungu’s favor. But in the event, voter turnout surged to 70% (from 58% in 2016), with younger citizens eager for change.

Political Shifts Can Be Spontaneous or Formal

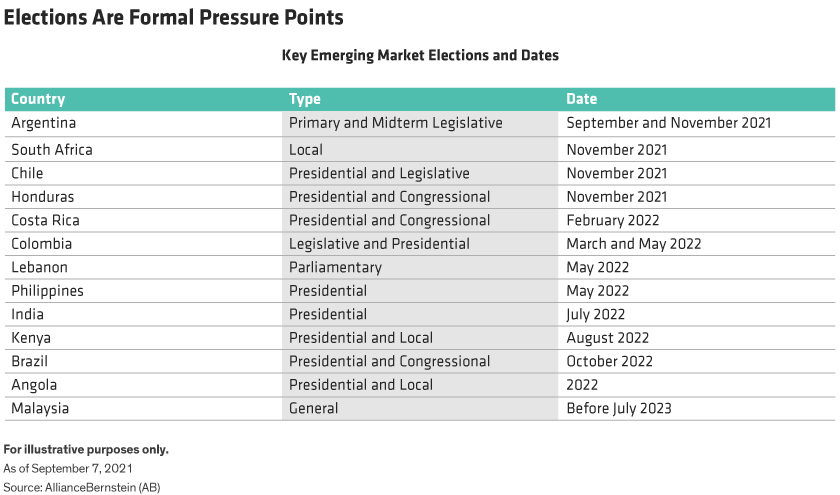

Spontaneous political shifts might become normal in post-pandemic conditions, but elections will remain formal pressure points and can flag potential positive or negative turning points (Display, below).

Over the next year, several African countries will go to the polls, and the results could alter political and policy trajectories (Angola, Kenya and South Africa). Potentially controversial elections loom in Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica). And in Asia, while some elections (for instance, Malaysia and the Philippines) might not be front-of-mind for investors, we think it remains important in the wake of the crisis to track public sentiment and policy signals closely.

Key ESG Metrics Can Highlight Potential Pressure Points

While it’s impossible to predict every change in the political and policy landscape, paying close attention to ESG metrics can help identify where the temperature is rising the fastest. As we’ve seen, poverty and income inequality are key drivers of populism. Demographics can also be an important factor in unemployment rates and appetite for change. And poor governance records can exacerbate social problems and prevent timely or effective reform. While emerging economies still have great potential, it’s important to fully assess each country’s ESG status to evaluate all the risks.

Adriaan du Toit is Senior Economist—Africa at AB.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..