by Rick Rieder, CIO, Fixed Income, Blackrock

“You can't always get what you want

But if you try sometimes, well, you might find

You get what you need”

“You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” The Rolling Stones (Let It Bleed, 1969)

When the Rolling Stones wrote these lyrics back in 1969, they probably didn’t have asset managers, insurance companies and banks in mind – and certainly not in the aftermath of a pandemic half a century later. But as most financial asset returns continue their relentless march higher in 2021, amid new waves of fiscal and monetary stimulus, investors are increasingly being forced to confront, however reluctantly, the growing tension between their wants (assets purchased with a margin of safety) and their needs (income).

The source of that tension? The very policies aimed at arresting the disruptive impact of the pandemic on financial markets last year. Monetary and fiscal policy have combined to incredible effect, stabilizing markets, and the economy: central bank liquidity injections and fiscal stimulus amount to 57% of U.S. GDP and 36% of global GDP, respectively, and continue to rise. These policies were so effective in fact that when combined with the accelerating vaccination effort (500 million “first doses” of vaccines have been administered versus 150 million Covid cases worldwide), by the end of 2021 the U.S. economy will likely have closed its output gap. Then, we think the U.S. economy should be well equipped to operate above equilibrium levels for some time thereafter (as described in our recent commentary Unprecedented Times).

Is There a Disconnect Between Economic Policy and Reality?

One would not necessarily come to this conclusion based on the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) comments from its April 28 FOMC meeting though. While the Fed acknowledged some improvements, they reiterated that these improvements “[do] not constitute substantial further progress,” and that it was “too soon to talk about tapering” asset purchases, as “[they] are a long way from [their] goals.” Given that statements of similar effect had been made at prior meetings, dating back to as early as October of last year, despite a remarkable improvement in the economic data since that time, it’s no wonder that the “bull market in everything” continues to persist, with emergency policies in place amid a rapidly evolving economic expansion.

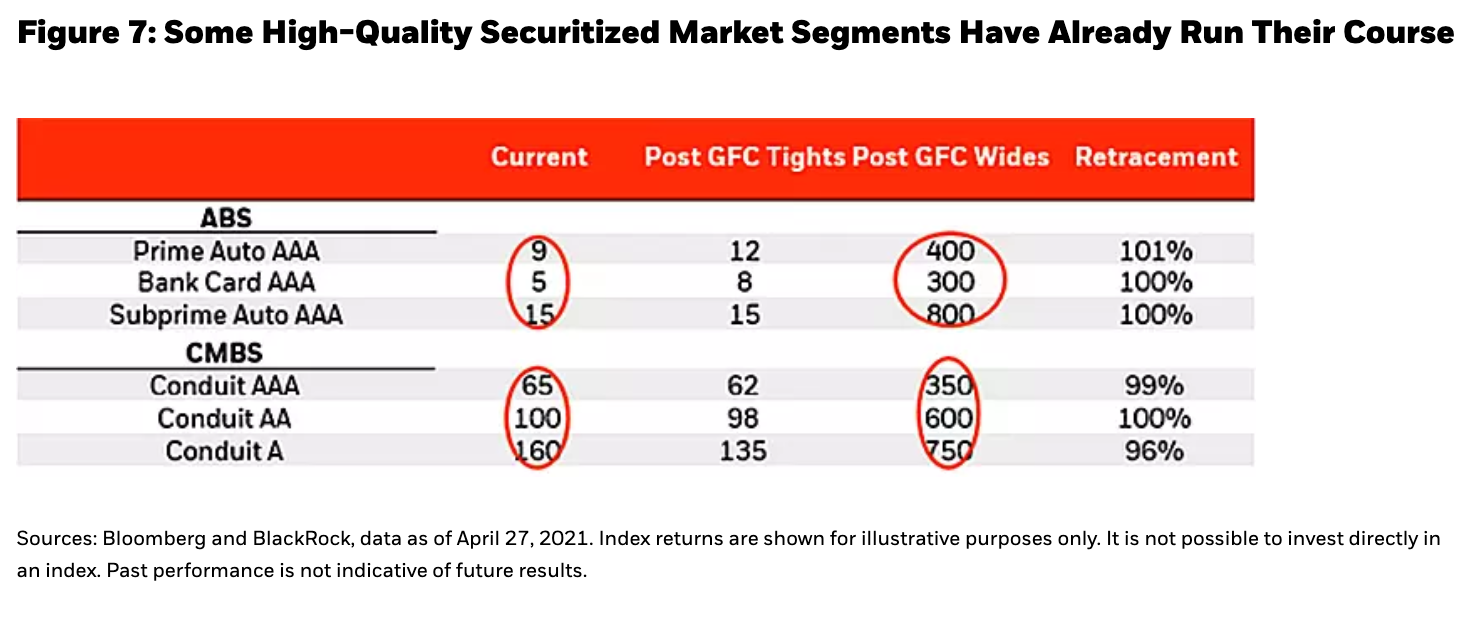

But at some point, doesn’t policy have to confront economic reality? If economists’ forecasts of GDP are to be realized (and we think they are in fact likely too low), then real rates will not have deviated this much from real GDP in the entire history of the TIPS market, since its inception in 1997 (see Figure 1).

We think that we’ve reached an ideal point for a reconciliation between policy and the real economy and thus that emergency policies should hand over the baton to vaccine-driven economic velocity as the U.S. economy gets back on its own feet. Inventories in many segments of the U.S. economy are at their lowest levels in history (housing and auto sectors, as cases in point), at the same time that personal income and savings have never been higher, suggesting record-shattering pent-up demand.

We think that we’ve reached an ideal point for a reconciliation between policy and the real economy and thus that emergency policies should hand over the baton to vaccine-driven economic velocity as the U.S. economy gets back on its own feet. Inventories in many segments of the U.S. economy are at their lowest levels in history (housing and auto sectors, as cases in point), at the same time that personal income and savings have never been higher, suggesting record-shattering pent-up demand.

The longer the delay in policy evolution, the narrower the window in which an eventual policy correction will have to be squeezed, risking a disruptive adjustment. Indeed, we think that monetary policy that is intentionally late, or disconnected from current economic reality, has the potential to create a new set of problems, such as financial instability. As investors, we have to manage our portfolios in a manner that captures the upside from continued (overly) easy policy, but which limits exposure to the potential fallout from a late, or disconnected, policy stance. There are three arguments that tend to be used in support of prolonged easy policy, and against the notion of normalization, or tapering, but none of them carry sufficient weight, in our opinion, versus the left-tail risks:

- The first of these arguments surrounds employment. Despite some extraordinary data, there are still millions of unemployed individuals who had jobs prior to the Covid crisis. Yet, monetary policy is a very blunt tool for promoting recovery from 2020’s unique economic crisis that affected different sectors in vastly different ways. It was absolutely necessary to use emergency policies in early-to-mid-2020, but the fact is today there are many segments of the economy where the primary employment problem is not a lack of demand, but instead rather extreme labor shortages (including epicenter sectors like Manhattan restaurants, believe it or not). Furthermore, an ageing workforce means that it will be increasingly difficult to reach prior peaks in employment, since the number of retirees is growing larger each year, while the trend of early retirement may have been accelerated by the pandemic.

- The second argument against policy normalization involves the inability of inflation to sustainably exceed the Fed’s 2% target. Still, we have written extensively about inflation’s growing ineffectiveness as an economic speedometer, not least because of changes in demographics, consumption, and supply elasticity (driven by technology) over recent decades (read more in our recent piece on Intangible Inflation). While the Fed is right to look through near-term base-effects, markets are more optimistic on corporate pricing power (based on earnings expectations), and on general prices over the next 5, 10 or 30 years than they have been in nearly a decade (based on the level of inflation breakevens), presumably given the influence of massive monetary accommodation married to relatively large fiscal spending.

- The final argument against tapering central bank asset purchases revolves around a fear of 2013’s “taper tantrum” being repeated – specifically, the memory of a multi-week period in which asset prices fell, in some cases sharply, as global liquidity was perceived to be on the brink of removal. However, in hindsight the taper tantrum barely registers in multi-year charts of asset prices and had an insignificant impact on sectors in the real economy, like employment, manufacturing (as per the ISM survey) and housing starts.

Follow Rick Rieder on Twitter

In our view, accommodative policy working toward further job gains, and particularly to improve social conditions (as Chair Powell has referenced), still makes tremendous sense. Yet, overstuffing the system with liquidity won’t enhance social conditions, nor will keeping rates at zero. Evolving policy away from emergency conditions, such that it is sufficiently and efficiently accommodative, while avoiding the potential for overheating pressure in the financial economy, and potentially in the real economy, is the direction we think the Fed should go.

Credit spreads and risk assets are largely already pricing in our expected destination of an economy operating at its potential. Leaving emergency policies in place for too long may push capital into areas that are already fully priced, risking the build-up of excesses that when forced to unwind, could cause instability risks that would be harmful to the economy. History is replete with examples of asset bubbles, from tulips in the 1600s to houses in the 2000s, but to be clear: while we do not yet see signs of that kind of irrational exuberance at this moment, it isn’t a risk the central bank would want to allow to develop, as it could undo the good economic healing already in place.

Making Sense of Market Crosscurrents

It is in this type of confusing environment, of a tremendous growth rebound amidst concerns over different forms of overheating due to policy being late to normalize, and the uncertainty of an ultimately harsher policy unwind, where what investors want to do can be very different from what they need to do – the opposite, or mirror image, in fact.

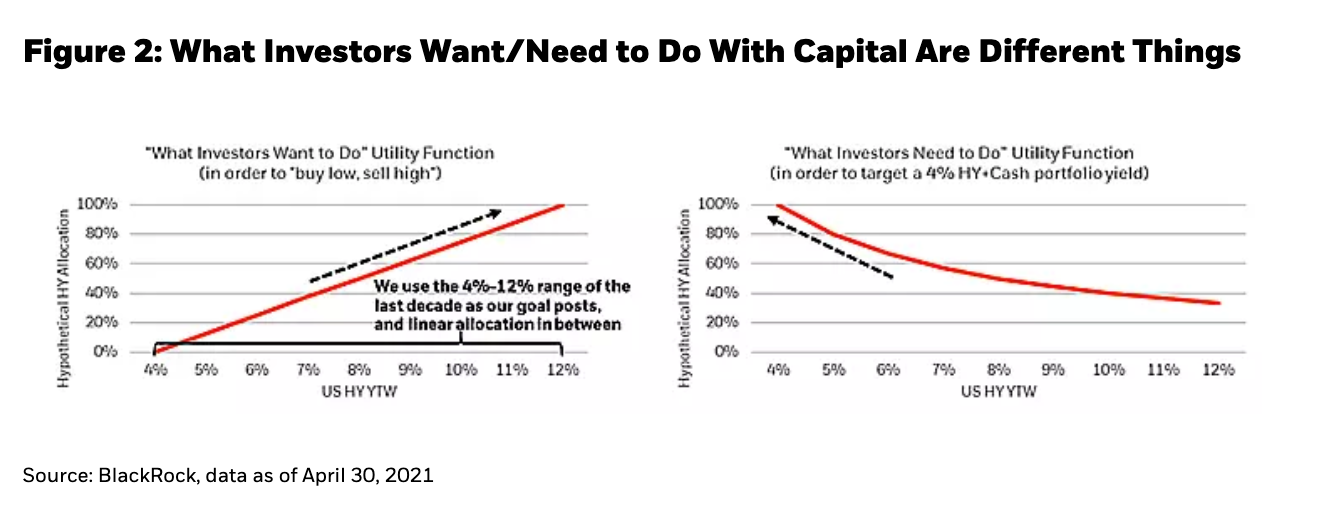

Investors generally want to “buy low, sell high:” which is to say, to buy more bonds at higher yields (lower prices) and fewer bonds at historically low yield levels. However, what investors often need to do is to meet income requirements in order to match liabilities. Hence, they are often forced to buy more bonds at lower yields (to raise sufficient dollars of future annual income), such that they end up being overweight when yields are at their lowest. Over the last decade, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. High Yield Index has traded in a yield range of about 4% to 12%, and both those extremes have come during the pandemic period (the last 14 months). At a 4% yield, an investor may want to own no high yield at all, but they may need to own a lot of it (see Figure 2). Since our last call, we have been blown away by how investors’ needs have dominated the market, against our fears of prices that were too high, and amid surging policy liquidity.

Interestingly, recent earnings reports revealed that the banking system may be another unwitting participant doing what it needs to instead of what it may want to. Surging bank deposits (partly a function of stimulus checks) alongside muted loan growth continue to drive the movement of excess cash into high quality, liquid assets – forcing up the price of these assets – not because the banks necessarily want to buy bonds with historically low yields, but because they need to in order to meet regulatory requirements.

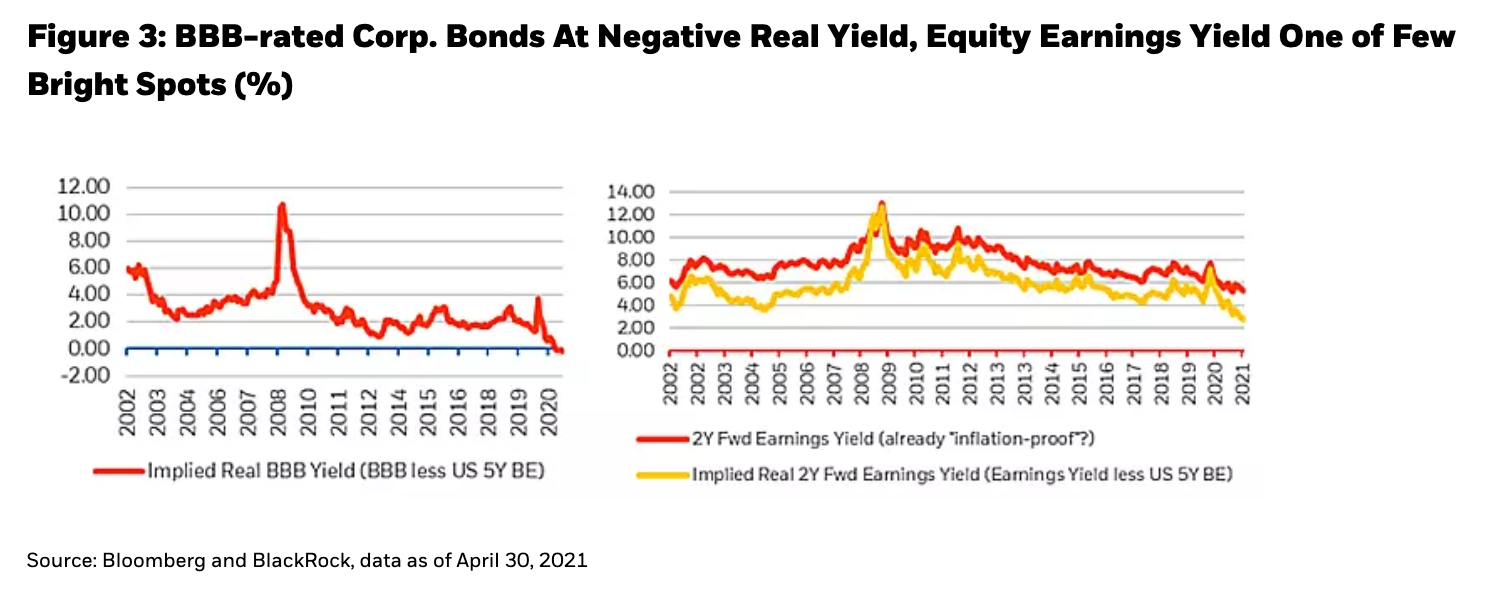

Simply put, what market participants want and need to do is to protect the purchasing power of their capital – but that has never been more difficult. Capital that is in search of a positive real yield (adjusted for inflation) is being forced into a shrinking pool of assets. This is the first time in history that BBB-rated corporate bonds do not offer a positive real yield (see Figure 3), in data going back to at least 2002, while BB-rated bonds (a subset of the high yield market) only barely make the cut. One has to go to the bottom of the capital stack (to equities) to find a positive real yield greater than 2% – and equity earnings are already somewhat “inflation hedged,” given companies’ ability to manage selling prices and costs, meaning that equities have a reasonable margin of safety against the market’s expectations of future inflation.

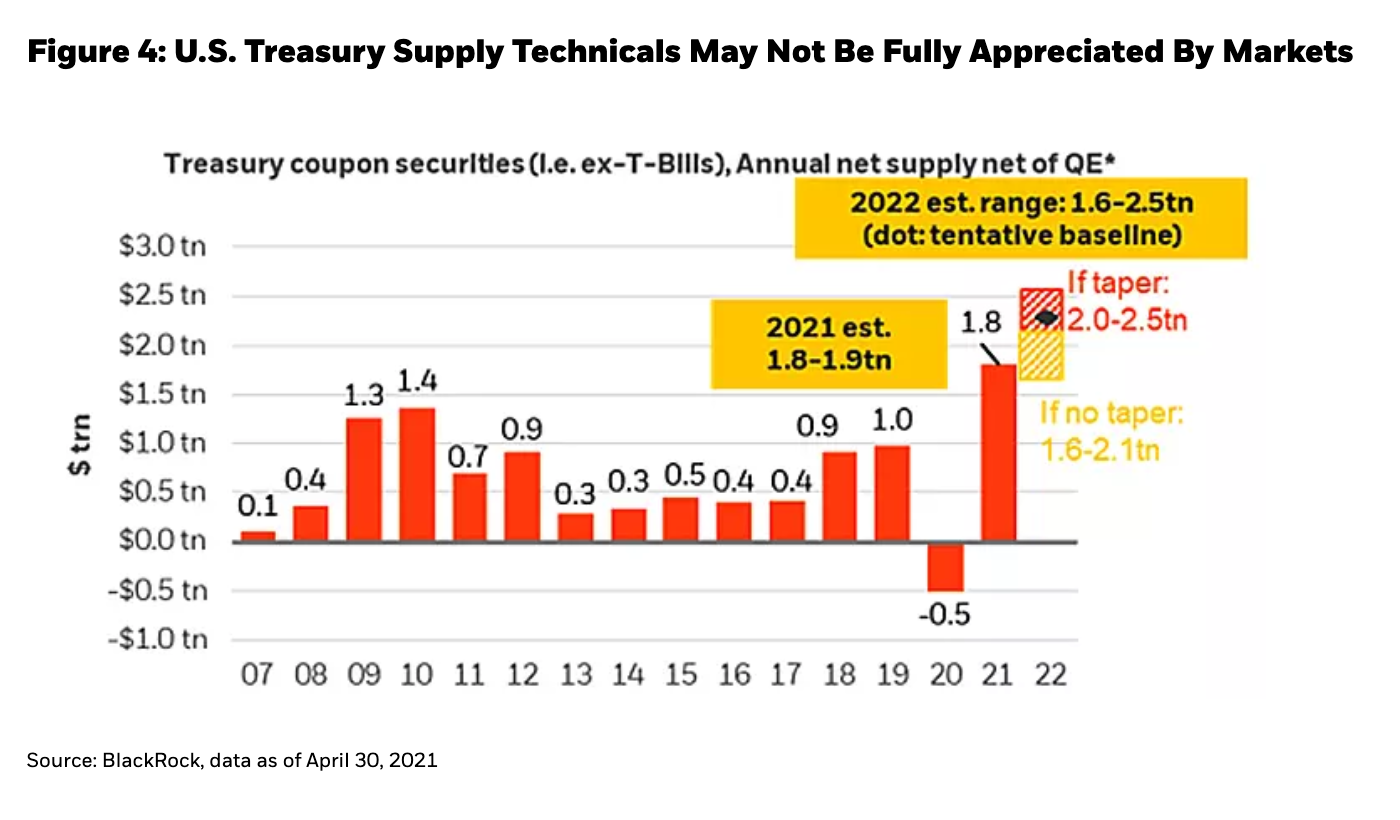

So, while we wait on the Fed, and actually because the Fed is moving slowly, technical factors may dominate financial markets in the near term. Investors continue to be forced to address their needs rather than their wants, while their capital bases grow at a torrid pace, fueled by ongoing liquidity injections. While technical factors surrounding market participants’ needs may be supportive of U.S. Treasury prices in the short term, the structural supply technical is decidedly unsupportive, given the likely trajectory of fiscal policy. In fact, about $6 trillion of spending initiatives have been announced in the Biden administration’s first 100 days, and while not all will be passed, most signs point to a greater willingness on the part of policymakers around deficit spending.

While we agree with the use of proceeds and the sentiment behind many of these (urgently) necessary spending plans, what does it mean for Treasury supply? The market will need to absorb a lot more duration risk than it is used to – triple the monthly volume of DV01 as it had in the last decade, in fact, persisting every month for the next two years (see Figure 4). Those are large numbers and the implications may not be fully understood by markets yet and may become a significant macro headwind later this year, but for now, techincals still dominate.

There’s no Playbook to Use Today

If exceptional real economy velocity, emergency monetary policy, generational fiscal policy and investors needing to buy assets were not enough to propel financial asset prices higher, then perhaps $1 trillion of delayed Covid quantitative easing (QE) would be? The fact is that more than $1 trillion of Covid QE was temporarily warehoused by the U.S. Treasury during 2020, and it’s being released into the economy during 2021. At the onset of the pandemic, Fed liquidity injections more than offset initial deficit spending. Thus, the proceeds from excess 2020 Treasury borrowing were temporarily warehoused in the Treasury’s General Account (TGA) at the Fed. As the TGA is drawn down to fund 2021 fiscal stimulus, it is essentially releasing 2020 QE, as if a stuffed piggy bank were suddenly broken open and released into an already booming economy. So far, 2021 is the only time in history that crisis-levels of policy liquidity has been injected into a booming economy with equity markets at record highs.

That rosy picture for financial assets explains how not a single major asset class posted a negative return in April 2021. Furthermore, liquidity’s dominance in setting the rules of the global macro landscape have resulted in virtually all assets becoming positively correlated to each other, and to the supply of cash dollars (something we have written about previously in The Policy Liquidity Monopoly).

Investment Implications

So, what does this mean for investing? Thinking about the opportunity set in fixed income today, we’d suggest that valuations are somewhere between fair and quite full, depending on the market segment. Building a diversified portfolio around the 2% to 4% yield range is feasible, though there is very little that we would consider to be “attractively valued,” and there are very definitely market segments to avoid all together (see Figure 5).

Emerging markets debt (EM) offers more attractive yields than can be found in most developed markets (DM), although the spread between emerging and developed rates is at five-year tights. The China rates market stands out as a bright spot - China seems to be making an intentional effort to provide stability at the sovereign yield and real economy level, which at yields north of 3% certainly makes a strong case for an allocation. Nonetheless, despite a dearth of absolute value, we expect significant dispersion (or convergence) between markets that will allow for attractive relative-value investment opportunities.

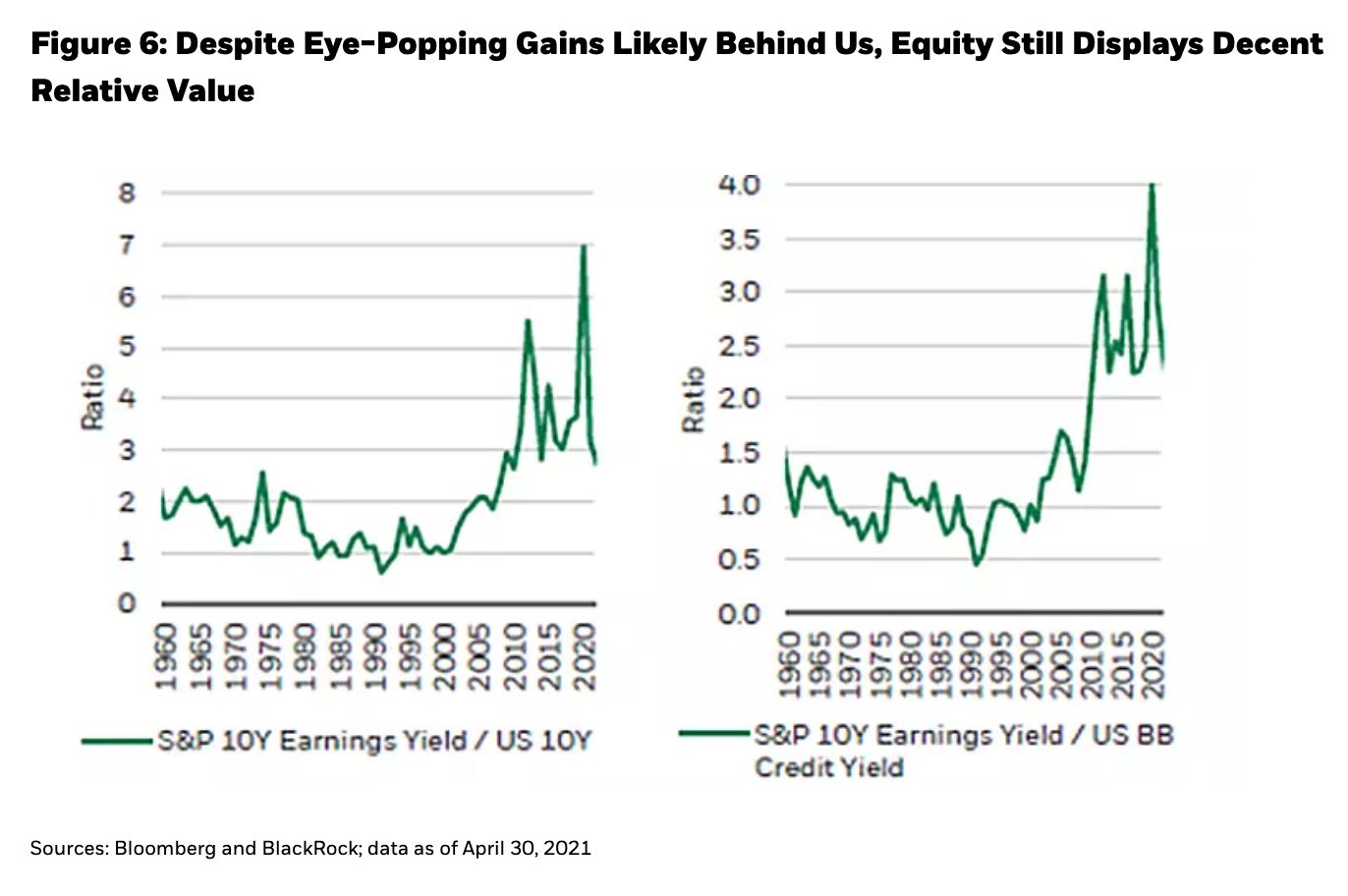

We’ve also come a long way in the equity market over the last year. While we see less value in the equity market today than a year ago (when valuations were just incredibly supportive), we still believe the current investment regime of high growth and high liquidity is supportive of equities. While the eye-popping gains of the last year are probably largely behind us, there is still some solid relative value present, given the high real yield available in the U.S. equity market, as opposed to the negative real yields available in most fixed income assets (see Figure 6).

In this operating regime, we think that portfolio construction needs to move more nimbly, along with greater asset-selection diligence, supplemented by heavy levels of cash (to take advantage of potential opportunities that present themselves, as described in The Queen’s Gambit Declined). We remain absolutely amazed at the massive technical conditions that played out in interest rate markets over the past month, and particularly in real rates, with a Fed still willing to press financial conditions easier alongside of potentially immense continued fiscal policy and subsequent TGA disbursements.

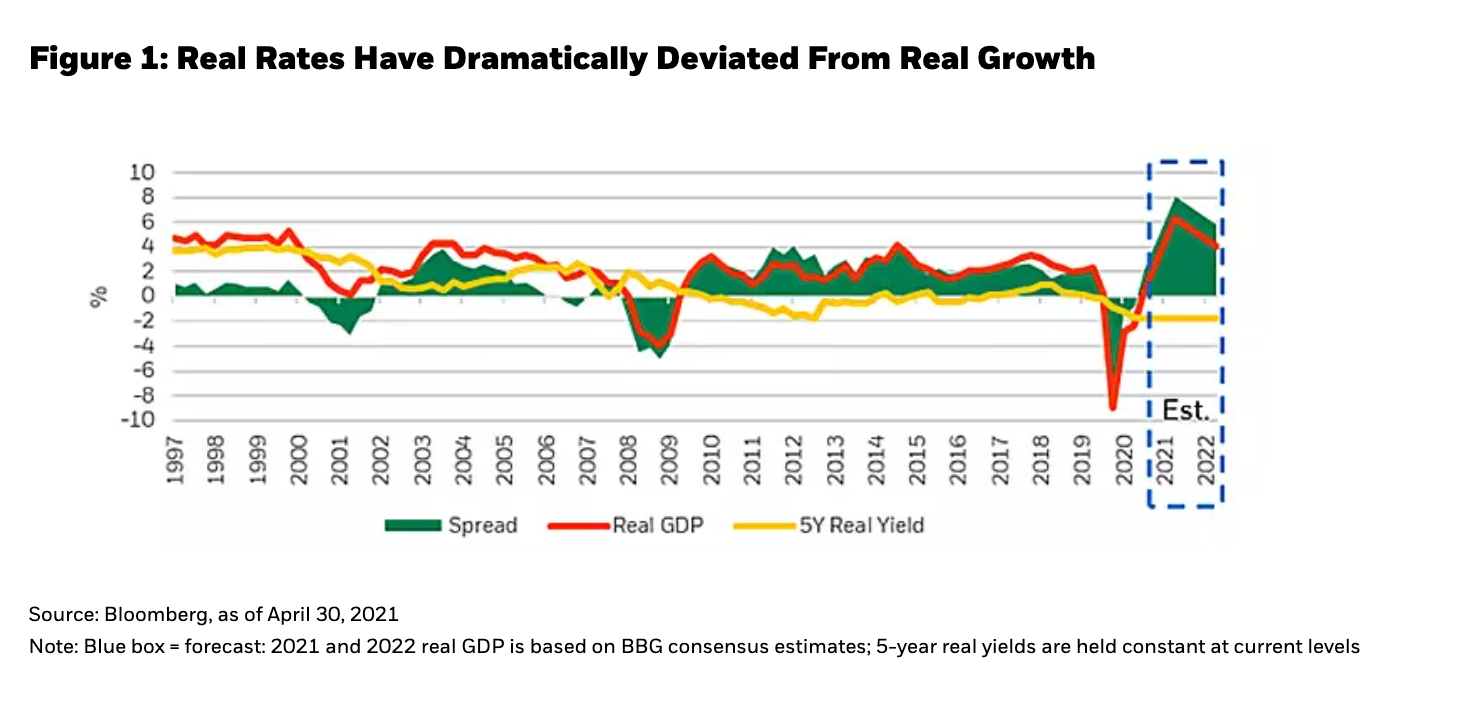

When we think about this continued policy push, and the easiest financial conditions in history, we want to own equities and some securitized assets, while acknowledging that some very high-quality segments of the securitized markets have already run their course (see Figure 7). For the next few weeks, we will probably need to own mispriced Treasuries and Agency mortgages, keeping one finger on the exit button for when the Fed finally sees enough ”substantial further progress” in the data to adjust its existing monetary policy directives. We have learned over the years that investing based on what policymakers are doing is a more rewarding philosophy than investing based on what one thinks should happen. Hence, the immense liquidity being pushed into the system today means investing in some things because one needs to, regardless of what one may want.

Rick Rieder

Rick Rieder

Rick Rieder, Managing Director, is BlackRock’s Chief Investment Officer of Global Fixed Income and is Head of the Global Allocation Investment Team.