Infrastructure merits more investment, everywhere; we look at the specifics of the U.S. proposal.

by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

IN THIS ISSUE:

- U.S. Infrastructure Bill: Far Beyond Transportation

- International Infrastructure Differences

- Closing the Digital Divide

Last week, President Biden formally proposed a multi-trillion dollar package of infrastructure spending. It’s large, and it covers much more than just roads and bridges. The debate surrounding the program is likely to be just as far-ranging.

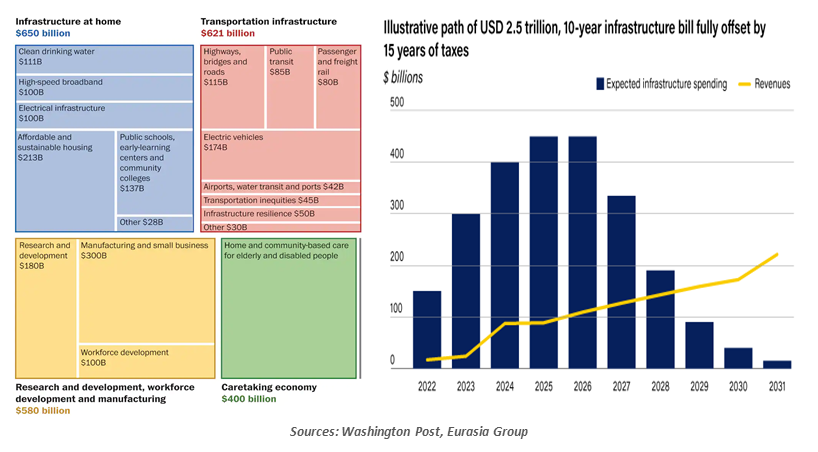

Reviewing the proposal, the first item that stands out is its title. The American Jobs Plan (AJP) omits the key word of “infrastructure” from its name. Fittingly so, as it has much wider aims. Key investments would be made in the following areas:

- Transportation infrastructure, including roads, bridges, the rail network and airports. The largest and most novel share of this section is $174 billion to develop an electric vehicle charging network and electrify the federal vehicle fleet.

- Domestic manufacturing, research and development, and job training, including a broad array of investments to improve supply chains and train workers.

- Home care and support care services, including more federal funding for long-term elder care.

- Housing stock, schools and hospitals, which would receive grants to improve their existing facilities and build new buildings.

- Broadband, the electrical grid and the water supply. The goal of bringing high-speed internet access to the whole country is discussed later in this publication.

Including the costs of tax breaks, the AJP is estimated to cost $2.6 trillion over eight years. In total, it reads much like the proposals Biden shared during the 2020 campaign. It differs from the pre-election outline mainly in the structure of the tax increases proposed to pay for it.

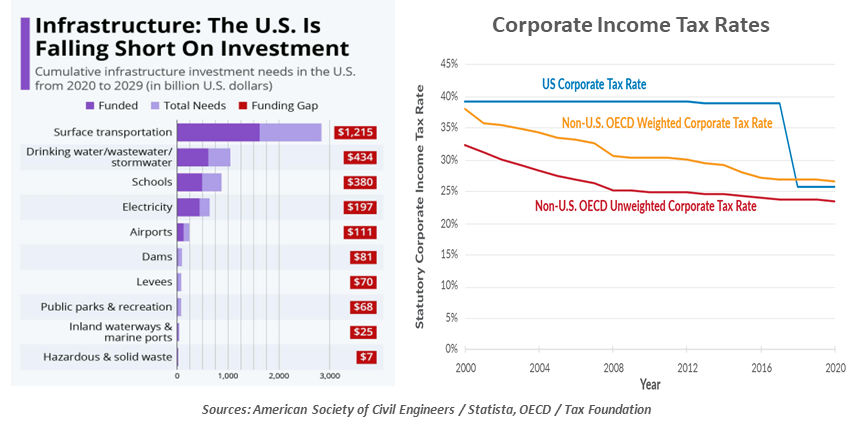

The AJP proposes to raise the federal corporate income tax rate from 21% to 28%. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) reduced this rate from 35%, and, unlike some TCJA provisions, the cut was meant to be permanent. The Biden proposal also includes provisions to increase the global minimum tax rate on U.S. corporations from 13% to 21%, place a minimum tax on corporate income, and remove incentives to register corporate headquarters or intellectual property overseas. Reforming international taxation will require complicated multilateral negotiations; this week, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen began a public overture among advanced economies to stop the “race to the bottom” of lower tax rates.

Any proposal that increases any taxes will be hotly debated.

The proposal omits any increase to personal tax rates. This is a refreshing break from Biden’s election platform, which included a marginal tax rate increase for high earners and would have unified the tax rates paid on income and capital gains. These ideas, as well as an end to the cap on state and local tax deductions, could reappear in the course of legislative debate.

The administration estimates that the new tax structure will offset the cost of the proposed spending after 15 years. This misalignment is novel: Congress holds itself to a rule that legislation should be deficit-neutral within 10 years. Approving a plan that spends in eight years but offsets over a 15-year horizon will be the first of many conceptual hurdles for Congress to clear.

The administration has expressed a preference for a bipartisan outcome. Improving public infrastructure is a goal most politicians support, but deals often fall apart when considering specific projects and the ways to fund them. A smaller package with little to no tax increase could attract some Republicans. However, Democrats have their own coalition to maintain; its more left-leaning members have already decried this proposal as too small to address the challenges of climate change. Bipartisan discussions may begin, but we do not expect them to be fruitful.

Democrats will be left to advance a bill with their narrow House majority and fragile 50 votes in the Senate, using the reconciliation process. Reconciliation allows fiscal measures to pass the Senate with a simple majority vote. Though a ruling this week expanded the frequency with which it can be used, it still only applies to measures related to taxation (which this bill contains) and mandatory spending (which, it will be argued, includes infrastructure). While passage using reconciliation is possible, the constraints will be difficult to navigate. Debates over the recently-passed Rescue Plan already took reconciliation to its limits, and the minimum wage increase was excluded on this basis. The Senate Parliamentarian should expect to work overtime in the months ahead.

The AJP proposal differs from the Rescue Plan in its speed and goals. The Rescue Plan was meant to provide urgent relief for the COVID crisis, with immediate effects. The AJP will take longer to pass, and its outcomes will play out over the course of years. It will not provide an immediate boost to growth. At worst, the AJP risks causing a short-term economic drag if corporate taxes increase before any benefits of government investment are realized.

The final bill may be even larger than $2.6 trillion if it is combined with other reforms.

Looking ahead, we should settle in for a prolonged debate, as is appropriate for a large bill. The administration has made its opening gambit and is ramping up communications. Even within the Democratic party, specific measures like the size of tax rate increases are already the topic of debate. Aspects of the forthcoming "human infrastructure" proposal may be combined into this measure, increasing its size and complexity. We do not expect a vote before July, at earliest.

More fundamentally, the AJP represents an evolution in the role of the state. Keynesian economics calls for greater government spending to support employment in recessions, but the economy is poised for a rapid recovery from the COVID crisis without any further intervention. Economic policy since the Reagan era has pushed for smaller government and lower taxes, but the uneven economic performance seen in the past decade has invited a reconsideration of that strategy.

After many years of cautious infrastructure investment, there is a case to be made for catching up. But this bill, and the proposals likely to follow, suggest a more fundamental realignment toward bigger government. Investing in roads may make our daily trips smoother, but the debate over the AJP is certain to be bumpy.

Seeking Better Posture

The spine is one of the most important parts of the human body. It gives the body structure and supports a wide range of movement. In economics, infrastructure is considered the backbone of any healthy system. Ignoring infrastructure, just like ignoring spinal problems for too long, can be detrimental to economic and public health.

As highlighted above, infrastructure is not merely rail, roads and bridges. Infrastructure is everything that facilitates efficient movement of goods and services, and that connects workers to jobs. Good infrastructure improves competitiveness and helps ensure resilience in the face of unpredictable circumstances. Investments in clean energy and public transit can also help reduce greenhouse emissions, a growing global concern.

Infrastructure disruptions cost households and companies in low- and middle-income countries as much as $647 billion a year, according to the World Bank. The International Monetary Fund estimates that allocating an additional 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) to public investment can create about 7 million jobs directly, and 20 million jobs indirectly worldwide. Infrastructure can also be the answer to the problem of sluggish productivity growth seen in many advanced economies.

European states, on average, spend 5% of GDP annually on building and maintaining infrastructure, compared to a 2.4% outlay by the U.S. While not trivial, these outlays aren’t enough to meet maintenance and enhancement needs. The world’s economies will have to incur $3.7 trillion annually into infrastructure from 2017 to 2035 in order to keep pace with economic growth. More than half of this investment will be required in Asia alone.

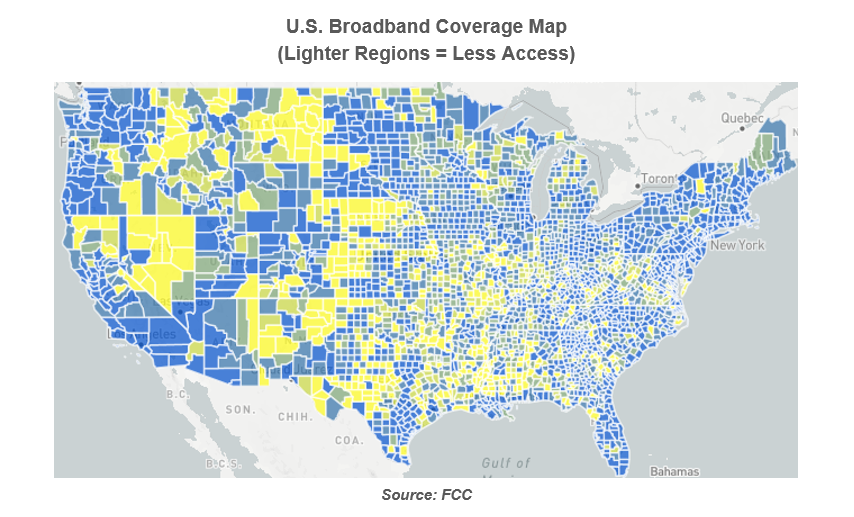

Singapore has the best infrastructure in the world, according to the Global Competitiveness Report 2019. The U.S. has slipped from fifth place in 2002 to 13th in 2019, and is lagging other developed countries like France, Germany, Japan, Spain and the U.K. In terms of broadband coverage, a key

requirement in today’s new normal of working from home, the U.S. lags its peers, ranking 18th. Even though Americans receive slower internet speeds than Europeans, they pay more for the service.

COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of strengthening infrastructure.

Generally, governments are best positioned to provide infrastructure, but inefficient spending along with poor public finances often end up being major constraints. Countries like Australia, Canada, France and the U.K. have national infrastructure frameworks in place that allow the central government to direct projects, something the decentralized system of the U.S. has struggled to do.

Higher government spending also doesn’t automatically imply improved infrastructure. Italy has one of the highest levels of government spending as a share of GDP, well ahead of many others, yet the country ranks 18h in the World Economic Forum’s index for infrastructure. Wasteful and unproductive spending are the key reasons. The country has witnessed several incidents of infrastructure failure in recent years from commuter trains derailing to bridges and more than 150 school roofs collapsing.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can play a bigger role in some nations, but can be contentious. PPP terms intended to protect residents from fee increases diminish investor incentives, and many projects do not create cash flows that would attract investors.

Though the U.S. proposal leads the news at the moment, policymakers across the world share the challenge of “building back better” after the pandemic. The world’s economic backbone needs to be strengthened to carry the load of the future.

Faulty Wiring

Carl comments on the need for investment in broadband access.

I made one of my best investments ever at the beginning of the pandemic. No, I didn’t buy Pfizer stock…I purchased a 100-foot ethernet cable that connects my laptop directly to my home router. It snakes through three rooms in the house, and isn’t aesthetically pleasing. But it guarantees uninterrupted internet access and high-quality video calls.

Access to high-quality internet service was a differentiator before COVID-19, but it has become even more important in the last 14 months. Employees rely on it to work remotely, students need it to attend virtual lessons, and vaccine-seekers need it to schedule appointments. Once a “nice to have,” broadband has become an essential service.

High-speed internet access has become an essential service.

Unfortunately, broadband access in the United States is not where it should be. A study from Broadband Now estimates 42 million Americans lack access to high-speed internet, and millions more cannot afford the service even when it is available.

The layout of the nation’s broadband grid has largely been left to providers, who (understandably) give priority to wiring areas that will be profitable. But this system has left gaps in both rural and urban areas. Research has shown these gaps impair economic performance and public health in the affected communities.

As part of its forthcoming infrastructure proposal, the Biden administration is asking for $100 billion to extend and enhance broadband access across the country. There is active debate on how best to deploy those funds: current service providers might be in the best position to extend their current networks, but would be reluctant to comply with the rate controls that the administration would insist on. Creating public networks, though, could be highly inefficient.

A century ago, electricity was evolving from a luxury to a necessity. But there were huge gaps in coverage because wiring remote communities was unprofitable. In that instance, government intervened productively; it is time for history to repeat itself.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/disclosures.