The road to a full economic recovery post-COVID may be paved with higher rates.

by Jurrien Timmer, Director of Global Macro, Fidelity Investments

Key takeaways

- Inflation expectations are on the rise as the economy continues to recover. Real yields are increasing at the same time.

- The recent rise in yields has started to alter the stocks-to-bonds relationship a bit. Right now, stocks and bonds are still negatively correlated but they have had periods of positive correlations in the past when inflation was rising—like in the 1960s.

- In my view, the Fed is likely to accept higher inflation and keep interest rates low, as they did in the 1940s, and emphasize full employment as their primary mandate. The question is, will this lead to structural (long-term) inflation?

Well, here we are, one year after many of us were told to go home. Little did we know that so many of us would still be working from home a year later. But right now, there seems to be more light at the end of the tunnel: from zero to 100 million vaccinations, and hospital beds occupied by COVID patients down by two-thirds.

Between COVID cases and vaccinations, some estimate that the US could be approaching herd immunity this summer.

With the percentage of US hospital beds occupied by COVID patients falling from 19.3% in January to 6.2% last week, more and more states and countries are reopening. Against this backdrop, the recently approved $1.9 trillion fiscal package is going to hit an economy that is already recovering rapidly amid depleted inventories and constrained supply chains.

The prospect of an economy that can finally reopen "for real" is not lost on the markets. The bond market is in full taper tantrum mode, even though the Fed seems committed to doing no such thing (taper its stimulus, that is). The rise in nominal yields is (so far at least) completely divorced from any expected change in Fed policy. While the fed funds curve is starting to signal a rate hike or 2, those aren't expected until early 2026, which is 5 years from now.

But inflation expectations are on the rise, and now so are real yields. It makes sense, of course, since many now expect that there will be some cyclical inflation when the economy returns to full potential—and possibly beyond. It's also logical that an economy soon running back at full capacity may warrant higher interest rates.

But what's interesting is that the recent rise in yields has started to alter the stocks-to-bonds relationship a bit. A signal change in the stocks/bonds correlation from negative to positive would certainly be noteworthy with regards to the 60% stocks/40% bonds paradigm. So far, the longer-term (5-year) correlation remains comfortably negative. It's just less negative than it used to be. That trend could continue, driven by rising inflation. The correlation between stocks and bonds has been positive in the past and it could happen again.

The chart below shows a long-term history of the stocks/bonds correlation, which is measured by the 5-year correlation between the nominal return of the S&P 500 and the real return of the Barclays US Long Government Index (and the Ibbotson series prior to that). The peak negative correlation was in 2015 at −60% and currently is at −30%.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Source: Bloomberg, Haver, FMRCo, Morningstar. Monthly data as of 03/14/2021.

What does a change in correlation between stocks and bonds mean?

The implications of a change in the stocks/bonds correlation (should it happen) cannot be overstated. The next chart shows an analog between now and the 1960s. That decade was the last time the correlation changed from negative to positive. The correlation bottomed in 1960 and it flipped to positive in 1964. There are many parallels between now and the 1960s, from a regime of robust fiscal spending, to tax cuts in 1964, to social unrest in 1968, to stock market speculation during the 1966–1968 cycle.

The culprit behind the signal change in the stocks/bonds correlation in 1964 was, of course, inflation. In a 60% stocks/40% bonds world, if we can find a solution to fight inflation, we can find solutions for most everything else because it can be tricky.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. 1960 and 2015 were the trough in the 5-year correlation between nominal stocks and real bond yields. CAGR stands for compound annual growth rate. Source: FMRCo, Bloomberg, Haver. Monthly data as of 03/14/2021.

Currently, the spread between stock and bond returns is among the largest of the past 20 years, with stocks way up and bonds way down. The last time we had the jaws open this wide (with bonds negative and stocks positive) was during the original taper tantrum in the spring of 2013.

If the jaws, the gap between stock and bond returns, are to close again, I suspect it will be because bond yields could soon slow down their ascent or stop rising if and when they reach the 2% level for the 10-year (nominal). (Nominal yields are not adjusted for inflation.)

For bond yields to stop rising much further, the Fed will have to keep the printing presses running, not to mention extend the duration of those purchases. Think of it as an informal form of yield curve control.

When will the Fed eventually taper its asset purchases and change its forward guidance toward a normalization of interest rate policy? Not anytime soon in my view. For monetary policy, it seems clear to me that the dual mandate of full employment and 2% inflation has become more of a single mandate of full employment. They'll worry about inflation if and when it finally goes above 2% and stays there.

While unemployment is down substantially from a year ago, it's still a very wide gap, and not too far from the worst levels seen during the Great Recession. It all suggests that fiscal and monetary policy will remain at full throttle for some time to come.

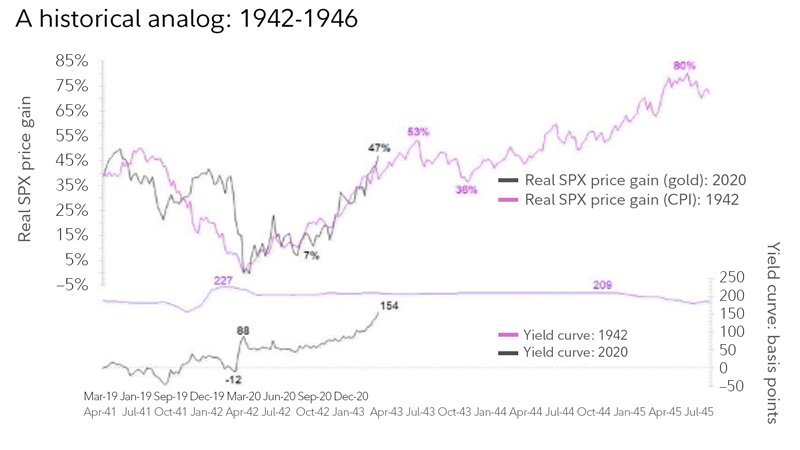

The 1940s analog

I continue to look closely to the 1940s analog for clues. During the 1941–1946 period, when the US government was mobilizing the economy to enter WWII, the federal debt tripled while the Fed increased its balance sheet 10-fold and capped both short and long rates at well below the inflation rate. It engineered a 2.5% long bond and a 3/8% T-Bill yield, or 0.375%.

In the process, it engineered a yield curve of around 200 basis points. I wouldn't be surprised if the Fed is eyeing a repeat of this scenario.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Weekly data as of 03/14/2021. Source: Bloomberg, FMRCo.

The net result of the Fed's rate suppression in the 1940s was that real rates fell well below zero and stayed that way for a number of years as inflation took root. In my view, the Fed today will accept higher inflation, as will the Treasury. How else is the country going to get out from under its rising debt burden? It's usually a good idea not to fight policymakers. If they want inflation, it might be a good idea to have some inflation hedges in our portfolios.

With the economy booming during the 1940s, the stock market enjoyed a broad-based rally, as shown by the breadth data below. Ultimately, midway through its 3-year 80% rally, the stock market did correct 11% in real terms, but that was a relatively mild and short correction in an otherwise robust 3-year-long bull market. There was a bigger decline later in the 1940s, however, as inflation really went through the roof.

Back to 2021: Inflation may be around the corner

As for the stock market and the economy one year later, while the unemployment/output gap is still open, it is closing fast and is doing so against the backdrop of an already booming industrial sector. We can see this in the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI). The latest reading in February showed the ISM PMI for the US rose to 60.8. A reading over 50 indicates an expansion.

In my view, inflation is next. The question is whether it will just be cyclical or whether it will also become structural. (Structural trends can span years or decades while cyclical trends come and go with the rise and fall of the economy.) I don't know the answer, but all my long-term charts suggest that it has the potential to become structural.

*****

About the expert

Jurrien Timmer is the director of global macro in Fidelity's Global Asset Allocation Division, specializing in global macro strategy and active asset allocation. He joined Fidelity in 1995 as a technical research analyst.

Copyright © Fidelity Investments