by Aleck Beach, CFA, Franklin Templeton Investments

As COVID-19 began to spread across the globe in early 2020, the global automotive industry endured crushing factory shutdowns. As it began to recover during the second half of 2020, a new challenge was taking shape in the form of a parts shortage that would soon ripple across the industry. The auto industry has long managed a complex supply chain of parts and components produced, shipped and delivered into assembly lines on a just-in-time basis. However, as auto factories went idle during government-mandated shelter in place orders, the shift to working and learning from home drove increased computing, networking and electronics needs.

What do cars, trucks, laptops and broadband networking all have in common? They all require semiconductors to function, and a shortage of these small but critical parts would soon begin disrupting auto production across the industry.

Semiconductors are used in a wide range of automotive applications such as airbags, instrument clusters, parking-assist cameras, engine and transmission functions, fuel pumps and windows. When semiconductor orders plummeted with factory shutdowns, steady demand from other industries redirected production capacity away from chips used in vehicles towards other end markets seeing stronger demand.

As auto factories eventually resumed production and vehicle sales rebounded faster than expected, tight semiconductor inventories and limited spare capacity have now resulted in a shortage of semiconductors for the global auto industry. As a vehicle rolls down the assembly line, the absence of just one part can halt production.

In trying to manage the shortage of semiconductors, vehicle manufacturers across the industry are taking targeted production downtime to protect assembly of high margin vehicles like pickup trucks and sport utility vehicles (SUVs) at the expense of lower margin products that are less in demand. The recovery in vehicle sales that began in the latter half of 2020 may slow over the coming quarters as semiconductor manufacturers work to bring supply back in line with demand.

During fourth quarter 2020 earnings reporting, US automaker Ford commented that a potential 10%-20% decline in first-quarter 2021 production as a result of semiconductor shortages could lead to a US$1 billion to US$2.5 billion reduction in profits if the shortage lasts through the second quarter. General Motors expects a potential negative impact of US$1.5 billion to US$2 billion.

European manufacturers are also seeing an impact, with Volkswagen, Daimler and Renault all expecting negative impacts to production. In total, industry estimates are that global vehicle production may be reduced by 1-2 million units through the first half of 2021, worth tens of billions in revenue. Should supply constraints last beyond the first half of 2021, the reduction to revenue and earnings will only grow, in our view.

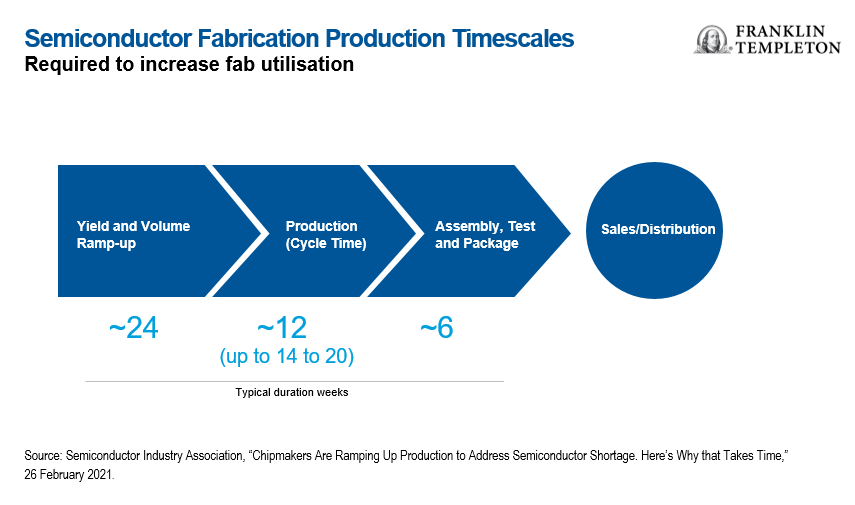

Manufacturing semiconductors is a complex process requiring hundreds of process steps on highly advanced manufacturing equipment. Production cycles typically run 12-16 weeks, while the most advanced chips can take up to 26 weeks to produce, according to industry estimates. Industry capacity utilization is currently high, so in addition to the time to manufacture semiconductor chips on existing equipment, additional capacity is needed which can take six to nine months to expand existing production lines. Given chip supply began to tighten in late 2020, the current supply-demand imbalance appears likely to last into the second half of 2021, in our view.

Chip Demand Likely to Continue Post-Pandemic

While a normalisation of recent supply shortages will happen over time, longer-term secular trends should continue to drive demand growth for semiconductors. As efforts to fight climate change are enshrined in tightening automobile emissions standards, the shift from internal combustion engines to electrified powertrains is poised to accelerate, and will likely drive continued growth in automotive semiconductors. Global electric vehicle (EV) sales grew over 40% to an estimated 3.2 million units in 2020 from approximately 2.3 million units in 2019, although only represents an estimated ~4% of global vehicle sales.1

Vehicle emissions regulations in Europe have recently tightened to a targeted industry average of 95 g/km of carbon dioxide, down approximately 27% from the prior target of 130 g/km, with further reductions targeted in 2025 and 2030.2 In addition, California has set an ambitious target that all new vehicle sales consist of zero emissions vehicles by 2035 and US President Joe Biden may introduce tougher national fuel economy standards. Global auto manufacturers all have a host of new electrified products coming to market to meet these tightening standards. While EVs are still a small share of global vehicle sales, market penetration is likely to grow substantially in the coming years.

Semiconductor content in vehicles has already been growing over time, and electrification is poised to drive further growth as electric powertrain architectures require semiconductor chips for key system functions like power management. According to industry research, non-powertrain related semiconductor content per vehicle is approximately US$400. Power management-related semiconductor content for mild hybrid vehicles drives an increase to US$570 of semiconductor content per vehicle, which further increases to roughly US$800 of content for plug-in hybrids and full battery electric vehicles.

Therefore, as EV penetration increases over time due to tightening government regulations, semiconductor companies stand to benefit from a significant increase in content per vehicle. Sensor and perception systems used in driver assistance and automated driving further add to semiconductor content per vehicle.

The present shortage in semiconductors and the impact to the auto industry is garnering heightened attention from policymakers. The Biden administration issued an executive order directing a broad review of supply chains for key materials, including semiconductors and rare-earth minerals used in electric vehicle batteries. This follows Congressional passage of the CHIPS for America Act as part of the fiscal year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. This new law calls for federal investment in domestic semiconductor manufacturing and research, but funding for these provisions requires congressional appropriations.

Current reductions to US auto industry production help shine a light on the need for US investment in high-tech industries like semiconductors, which may indirectly benefit the auto industry but may more directly benefit semiconductor companies.

In our view, the post-COVID-19 environment of robust capital markets discounting an eventual normalisation in consumer spending and economic activity is well-reflected in corporate bond valuations. As active investors, our job is to find the most attractive risk-reward opportunities in a market environment that does not offer an abundance of yield. This dynamic places a premium on identifying situations where earnings and cash flow growth may be superior in some sectors relative to others.

While the auto sector has seen a nice rebound in sales volumes, a continued recovery may be stymied in the near term by supply constraints in components such as semiconductors. Over the intermediate to longer term, continued growth in market penetration of electric vehicles appears likely to drive attractive relative growth in semi content per vehicle for related fixed income issuers. However, the semiconductor industry has a history of experiencing periods of not only supply shortages but also periods of excess. The current outlook for longer-term secular growth in semiconductor content per vehicle will need to be actively monitored for any signs that supply growth gets ahead of demand.

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Companies and/or case studies referenced herein are used solely for illustrative purposes; any investment may or may not be currently held by any portfolio advised by Franklin Templeton. The information provided is not a recommendation or individual investment advice for any particular security, strategy, or investment product and is not an indication of the trading intent of any Franklin Templeton managed portfolio.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton Institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Templeton Distributors, Inc., One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com—Franklin Templeton Distributors, Inc. is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton’s’ U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

CFA® and Chartered Financial Analyst® are trademarks owned by CFA Institute.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Investments in lower-rated bonds include higher risk of default and loss of principal. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value. Actively managed strategies could experience losses if the investment manager’s judgment about markets, interest rates or the attractiveness, relative values, liquidity or potential appreciation of particular investments made for a portfolio, proves to be incorrect. There can be no guarantee that an investment manager’s investment techniques or decisions will produce the desired results.

Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realised.

________________________________

1. Source:EVvolumes.com.

2. Source: The International Council on Clean Transportation.

This post was first published at the official blog of Franklin Templeton Investments.