The 2020 election dims the outlook for major legislation and aid to local governments, while central banks face the risk of a liquidity trap.

by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

Summary

- U.S. Election Results: A Government Divided

- State and Local Strain

- Monetary Policy Is Trapped

When asked how I slept, I often say, “Like a baby. I was up every two hours.” That’s what election night was like for many. Normal circadian rhythms have yet to be re-established, as updated vote counts and political analysis continue to paint an uncertain picture.

Much is still unknown as of this writing. Court cases and recount requests challenging the presidential balloting are being filed. Knowledge of who will control the U.S. Senate may not come until we have the results of runoff elections scheduled for early January. While the House looks likely to remain in Democratic hands, its working majority has diminished, making it more difficult to formulate a legislative agenda.

But there are a handful of insights that we can offer on the basis of the results we have in hand.

- Government will remain divided, potentially more so than before. The “blue wave” predicted by the polls failed to materialize; the high level of voter participation (the largest in a century) did not favor the Democrats, as some analysts anticipated. Neither party will have much of a working margin in the Senate, which will make it difficult to move legislation forward. The right to filibuster will remain in place, allowing either side to slow progress.

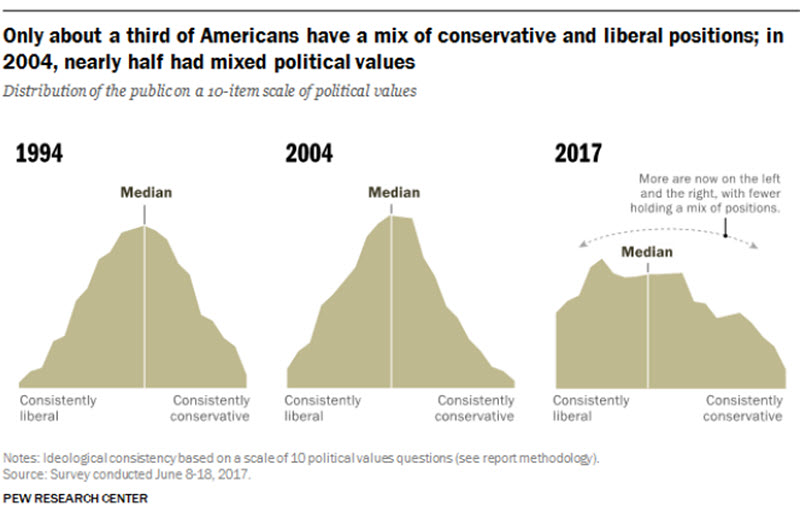

It bears mentioning that the fractiousness isn’t confined to inter-party matters. Getting caucuses within the parties to coalesce will continue to be a great challenge. Democrats have an increasingly active progressive wing, while fiscally conservative Republicans are reasserting themselves. Two recent Republican House Speakers stepped down from the post, partly out of frustration; Speaker Pelosi (should she be re-elected) may find it similarly difficult to govern. The shrinking middle ground in Congress is a direct reflection of a similar trend in the U.S. population.

- Hopes for a large economic stimulus bill have faded. Congress failed to get supplemental support over the line before the election, and the path to passage has narrowed.

Last month, Republicans in the Senate had advanced a $500 billion proposal primarily focused on aid to the unemployed and small businesses. The House had advanced a $2.2 trillion package, down from the $3 trillion bill it passed in August. Closing that gap now appears to be a bridge too far.

“Prospects for a sizeable stimulus package have dimmed.”

Without a blue wave, further economic support will take longer to craft and will likely be far less generous. Aid to state and local governments, which are struggling, is less likely to be a part of the program. We have reduced our assumption surrounding fiscal stimulus in 2021, and coincidently cut our growth forecasts. There is certainly a risk that the recovery could end prematurely for want of sufficient policy support.

The upcoming “lame duck” session of Congress is unlikely to produce much in the way of economic legislation. The exception might be additional funds for the medical community, whose resources are once again under stress as new COVID-19 cases escalate.

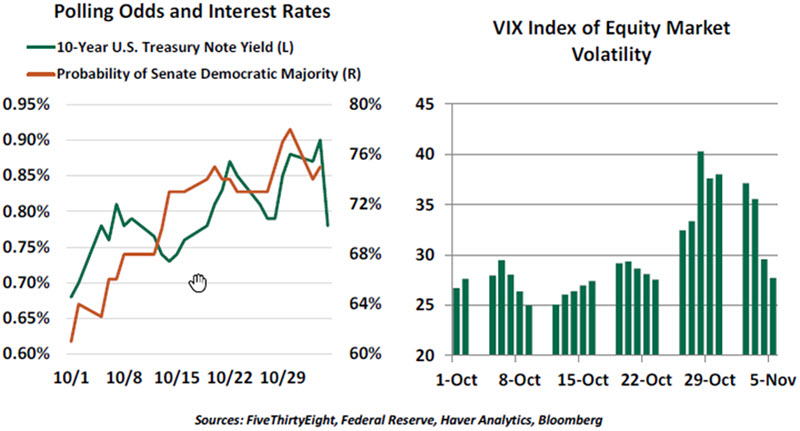

Markets have begun to adjust to a more austere future. Long-term interest rates fell on election night as Democratic hopes for a sweep dwindled. Volatility in the equity market also dropped off.

- Broad changes to taxes and ongoing spending are unlikely. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) narrowly passed at the end of 2017, at a time when Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress. Since neither side will enjoy much of a Senate majority, the ability to use the “reconciliation” process to fast track tax measures will likely be limited. It will therefore require 60 votes in the Senate to advance anything substantial, which seems virtually impossible.

The House of Representatives takes the lead on spending initiatives. With the Democrats losing seats and disagreement lingering among Democrats on what priorities to pursue, new mandates will be difficult to design. We continue to think reinforcing infrastructure might be an area of mutual interest, but as we discussed recently, the two parties have different views on the direction to take.

Changes to the U.S. tax code in the next two years do not appear very likely. By the same token, the new Congress is unlikely to take any action to extend elements of the TCJA, a number of which are set to expire in the coming years.

A divided government will almost certainly rule out sweeping changes to the American medical industry, or action to address climate change. Republican calls for more discipline surrounding Medicare expenses will also go unanswered. The national debt will likely continue to increase at an unsustainable rate.

- The future course of regulatory policy hangs in the balance. “Policy is personnel,” they say in Washington. Here, the final election outcome will be critical: the chief executive will appoint cabinet members (who will, in turn, appoint undersecretaries), but they must be confirmed by the deeply divided Senate. In recent years, getting government appointments through the legislature has become increasingly difficult, leaving agencies understaffed.

“The prospect of gridlock has cheered markets, but gridlock may not be the best thing for the economy.”

At this stage, it appears that environmental, anti-trust, financial and labor regulations are unlikely to undergo radical change. That said, President Trump has made active use of executive orders, a tactic that would certainly be available to the next administration.

One market observer suggested gridlock is good for equity markets, because it locks in light regulation and low taxes. But gridlock is not good for the U.S. economy, which is losing momentum amid rapid increases in COVID-19 cases. While there is reluctance to impose restrictions aimed at containing the pandemic (which might be hard to enforce), stressed medical capacity in some parts of the country may force preventative responses. For some citizens, the heightened risk of infection may be enough to curb their movement and their enthusiasm.

It will be a relief to have the campaign over with, and the outcome affirmed. But whatever the outcome, it seems unlikely the economic challenges we’ve discussed over the past few weeks will get the resolution they so desperately need.

All Politics Is Local

While the national election leads this week’s news, state and municipal governments are continuing to struggle under the strain of the COVID-19 crisis. And they are getting little help from their citizens and from the federal government.

The pandemic shocked local governments in several ways. Demand for their essential services grew: Laid-off workers overwhelmed state unemployment agencies, while lost incomes increased enrollment in Medicaid and other social services. Schools have been forced to invest in remote education technology and training, while law enforcement agencies dealt with sporadic civil unrest.

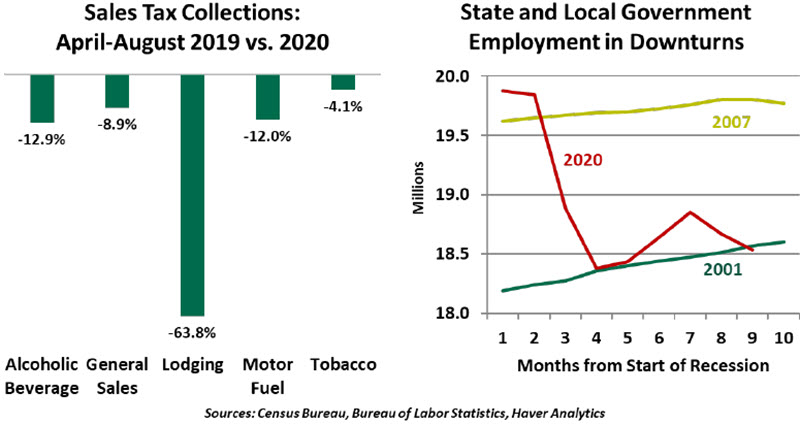

At the same time, sales tax revenue fell as consumers stopped spending on non-essential goods and most services. Though retail sales have recovered in many categories, highly taxed destinations like hotels and airports remain far below their prior levels of activity. Declining income taxes due to widespread layoffs further added to states’ pain. Governmental bodies responded by swiftly cutting headcount in a manner never seen in past recessions.

Support from the federal government has been fleeting. The CARES Act allocated $150 billion to fund state and local governments’ COVID-19 mitigation measures. Disagreement over the extent of further support to municipalities helped prevent passage of a subsequent round of stimulus, as some legislators viewed it as a bailout of states that were fiscally irresponsible before the crisis. But the loss of tax revenue affected every state, regardless of their fiscal conditions. Given the election outcome, additional support to local governments faces a steep uphill climb.

“Governmental bodies balanced their budgets with sweeping layoffs.”

Voters in several states were presented with fiscal referenda aimed at raising revenue, and they responded negatively. California’s populace defeated Proposition 15, which would have increased taxes on commercial properties. Colorado’s Amendment B was approved, which will prevent a reallocation that would increase taxes on commercial real estate. In Illinois, voters declined the “Fair Tax” proposal to replace the state’s flat income tax with a graduated one. Broadly, voters seem hesitant to accept any tax increases, even if they fall on other taxpayers.

As long as the economy remains dislocated by the pandemic, funding of government services will fall short while demand remains elevated. State and local governments could prove to be a significant economic headwind in the year ahead.

Get Out

Almost lost in the attention attracted by the U.S. election this week were three important central bank meetings. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the Reserve Bank of Australia are all facing a similar challenge: their economies are falling into a “liquidity trap.” It is a grim diagnosis: the trap signals a central bank’s inability to stimulate demand through conventional tools. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers once described liquidity traps as “the black holes of monetary policy.”

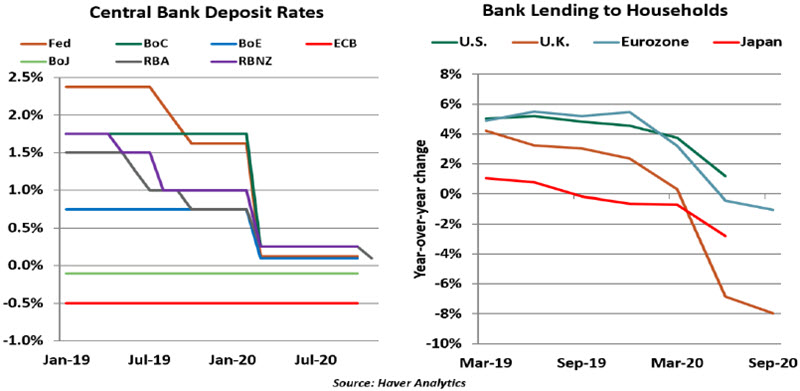

A number of world markets have a combination of low interest rates, low inflation, weak demand and a preference for saving over investing. Banks are reluctant to lend into an uncertain credit environment, and are being encouraged by regulatory authorities to manage their resources carefully. Under these conditions, the money a central bank injects into the economy does not circulate normally and fails to promote growth.

During the last crisis, central bankers were often the only game in town for stimulating economic growth. But they went into the crisis with lots of room to cut interest rates, which they do not have now. Central bank rates in almost all advanced economies are now below 1%, with some already negative. We think interest rate policy has reached its limit.

Many central banks are aggressively increasing the sizes of their balance sheets to flood their systems with liquidity, but they may be pushing on a string. Demand for credit is soft: household saving rates around the world have surged in the last six months. In the U.S., cash holdings of public companies increased from $1.96 trillion at the end of 2019 to $2.54 trillion in the second quarter of this year. European household deposits increased by 10.5% over the year to September, the fastest rate in over a decade.

Europe is closer to the black hole with little prospect of rates returning to positive territory. The eurozone relies heavily on its banking system for credit extension, but financial companies there are cutting back on lending. Japan is already in the hole and may go deeper. The U.S., with its unprecedented monetary measures and risk of a divided house in Washington limiting the scope for a sizeable fiscal response, may be next to fall in.

“With credit conditions tight, fiscal policy becomes more important.”

Liquidity traps risk setting off a deflationary spiral in which prices fall. Anticipation of further price drops causes people to delay spending, leading prices to fall even more. Abundant liquidity may trigger excessive risk-taking that leads to financial bubbles, while underperforming firms can continue to roll over their debts. (By one estimate, 18% of U.S. corporations would falter if not for the abundance of liquidity in the financial system.) A global liquidity trap also leads to competitive devaluation of currencies, as monetary policies contribute to weakening exchange rates.

While monetary policy becomes ineffective in liquidity traps, fiscal policy becomes more effective. Research suggests that the multiplier from government spending tends to be larger in a prolonged liquidity trap. Expansionary fiscal policies can help in reducing unemployment, and thereby reduce the need for individuals to hoard cash. But world is heavily indebted today, and policy makers have become hesitant to add further to their financial burdens.

In the end, stimulating growth is critical. Failing to do so could cause economies to fall into a trap that will be difficult to climb out of.

Copyright © Northern Trust