Canada’s central bank looks to evolve its policy framework amid concern over disinflationary trends.

by Vinayak Seshasayee, Allison Boxer, PIMCO

The Bank of Canada (BoC) is approaching a regular five-year review of its monetary policy objective, when it looks to renew the joint agreement between the bank and the government about the BoC’s framework. The 2021 review is likely to be particularly important. For the first time since 2001, the BoC is seriously considering changing its existing goals to make them more suitable to the persistent low-inflation, low-interest-rate environment Canada currently faces. To augment its current inflation target, the BoC is evaluating various alternatives via a “horse race” of potential alternative frameworks, including average inflation, price level, nominal gross domestic product (GDP) targeting, or a dual framework that would incorporate both prices and employment.

Still, we expect the BoC to reaffirm its existing flexible framework of inflation targeting and stop short of formally quantifying other objectives. However, while the framework itself may read the same, the BoC’s reaction function will likely be different from what we have seen in previous economic cycles. Specifically, we think the BoC will be significantly more measured and patient, raising interest rates only after seeing strong, persistent evidence of both inflation returning to target and the output gap closed, rather than preemptively hiking rates to prevent overheating. So, while the BoC is unlikely to follow the U.S. Federal Reserve in changing its framework, the implications for monetary policy are likely to be similar to the results of the Fed’s new monetary policy framework.

Why is a change in the framework being considered now?

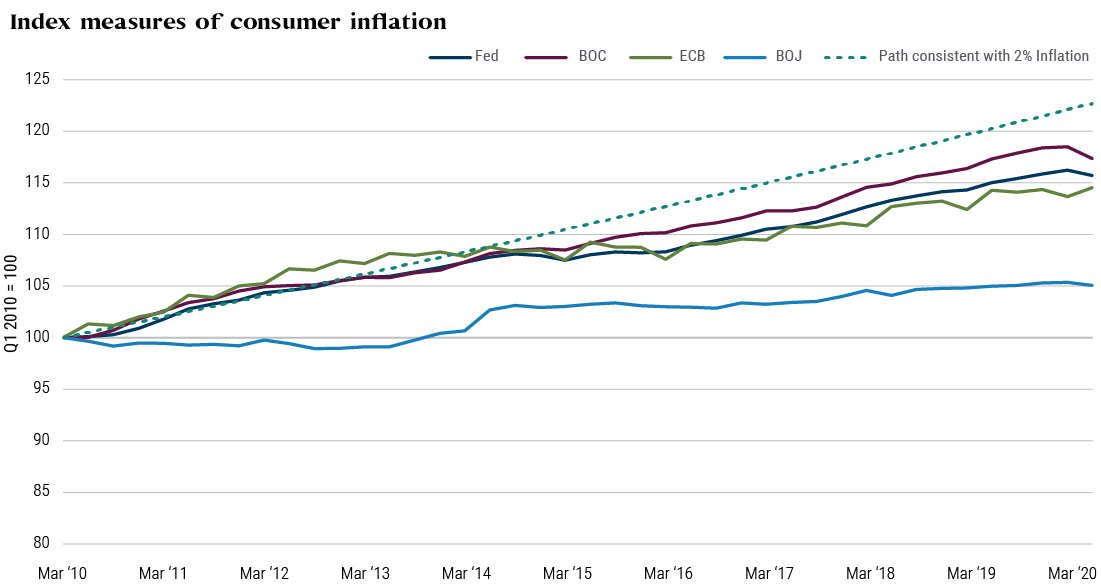

After moving to an inflation targeting regime in 1991, the BoC has been relatively successful in meeting its objective, with inflation averaging a generally stable 1.9%. The BoC targets the 12-month change in consumer price index (CPI) inflation at the 2% midpoint of a 1%-3% inflation control range. Relative to other developed market central banks such as the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan, the BoC has been much closer to achieving its inflation target over the past decade. Yet, more recently the BoC has been falling short of its objective, with annual inflation over the past five and 10 years averaging about 0.3%-0.4% lower than target (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bank of Canada has come closer to achieving its inflation targets than its peers.

Source: Bloomberg; data is for periods from 1 April 2010 through 30 June 2020.

Versus peer nations, Canada entered this crisis from a position of relative strength, with higher neutral interest rates, less government debt, and a smaller central bank balance sheet. Still, Canada is affected by the same structural headwinds that have lowered trend rates of inflation in several other developed markets – in some ways even more so. In our view, the risk of inflation expectations falling is significantly higher now than in previous cycles. Consider:

- COVID-19 has left Canada with a large output gap, which will likely create disinflationary tendencies as low growth weighs on prices.

- With the benchmark interest rate at the effective lower bound (0.25%), and the BoC unlikely to pursue negative rates for now, Canada faces an environment in which monetary policy is not well-equipped to respond to downside risks from new economic shocks.

- Debt and leverage are now significantly higher than they were in previous cycles.

- Trend growth and the neutral rate (the short-term interest rate that would prevail when the economy is at full employment with stable inflation) have both fallen.

- Demographics are acting as a headwind as the population has aged, and immigration has been curtailed in the near term as a source of labor supply.

- Studies1Footnote show experience affects inflation expectations. Today’s Canadian has, on average, experienced lower lifetime inflation than previous generations.

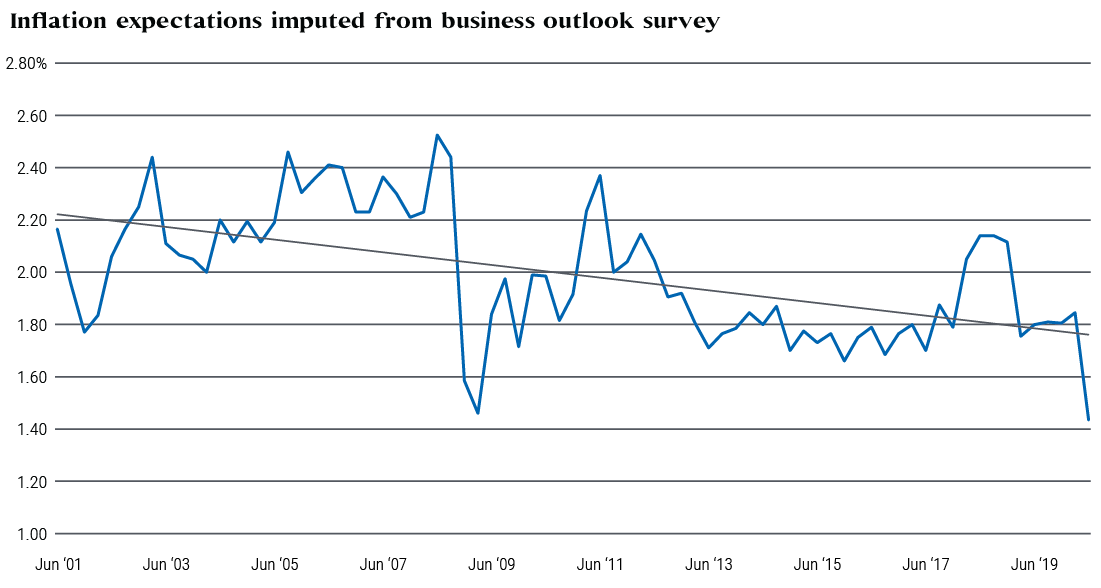

The most recent Business Outlook Survey (see Figure 2) illustrates the risk that inflation expectations could fall further. Nearly 25% of firms in the June survey expected inflation to fall below 1% -- the lower end of the operating range. All of these factors together underscore why the BoC is considering a more significant change to the framework at this review relative to prior years.

Figure 2: Inflation expectations have fallen to 20-year lows.

Source: Bank of Canada; data is for periods from 1 Feb 1991 through 31 Aug 2020.

Will the BoC make a revolutionary change to its framework?

The Bank of Canada could choose to fight these disinflationary risks by adopting an alternative framework that, for example, uses a monetary policy rule like average inflation or price-level targeting. We think there is a case for considering this more revolutionary option. The BoC was a trailblazer in instituting the inflation target, so taking a more revolutionary approach would not be new. Still, formally changing the framework would be a more revolutionary change than we expect and it would come with risks. A new strategy could be difficult to communicate clearly to the public, which risks undermining credibility, and a monetary policy rule requires relinquishing some flexibility. Given these trade-offs, we believe the BoC will stop short of explicitly changing its framework and will choose instead to emphasize them through regular communication. Thus, we expect the framework review will likely produce more evolutionary tweaks than revolutionary change.

However, similar to the Fed, even without a more revolutionary change in approach, we still think the BoC reaction function will likely be different than the hiking cycle that followed the Global Financial Crisis. During the 2009-2010 “lift off,” the BoC raised rates a mere 13 months after reducing them to the effective lower bound. We now expect the BoC to stay contained at the lower bound for much longer (until 2023 at the earliest), keeping short-term rates low, while allowing longer-term rates to absorb the impact of growth and recovery.

Investment implications

With short-term rates anchored at the lower bound, a combination of quantitative easing, ballooning budget deficits, and the pace of recovery is likely to drive longer-term yields. In our baseline outlook of a slow recovery, we expect longer-term yields to rise modestly as growth picks up and the deficit grows.

In our view, in a low-yielding but positively sloped curve environment, investors may look to actively benefit from these framework changes by:

- Positioning portfolios for steeper yield curves with an overweight to intermediate bonds against an underweight to long-term bonds

- Positioning for higher inflation break-evens as the BoC seeks to reflate the economy more aggressively, consistent with its framework; we view real-return bonds as attractively priced in the current environment, making them a potential alternative to longer-term nominal bonds

- Actively positioning to capture price appreciation through roll-down as an additional driver of total return beyond current yield across all sectors of high-quality fixed income

Read PIMCO’s blog coverage of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s latest monetary policy guidance: “The Fed’s New Guidance: Surprising Is Not Convincing.”

1 Malmendier, Ulrike, UC Berkley & Nagel, Stefan, Stanford University, Learning from Inflation Experiences, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 131, Issue 1, February 2016, • Pages 53–87 ↩