by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Franklin Templeton Investments

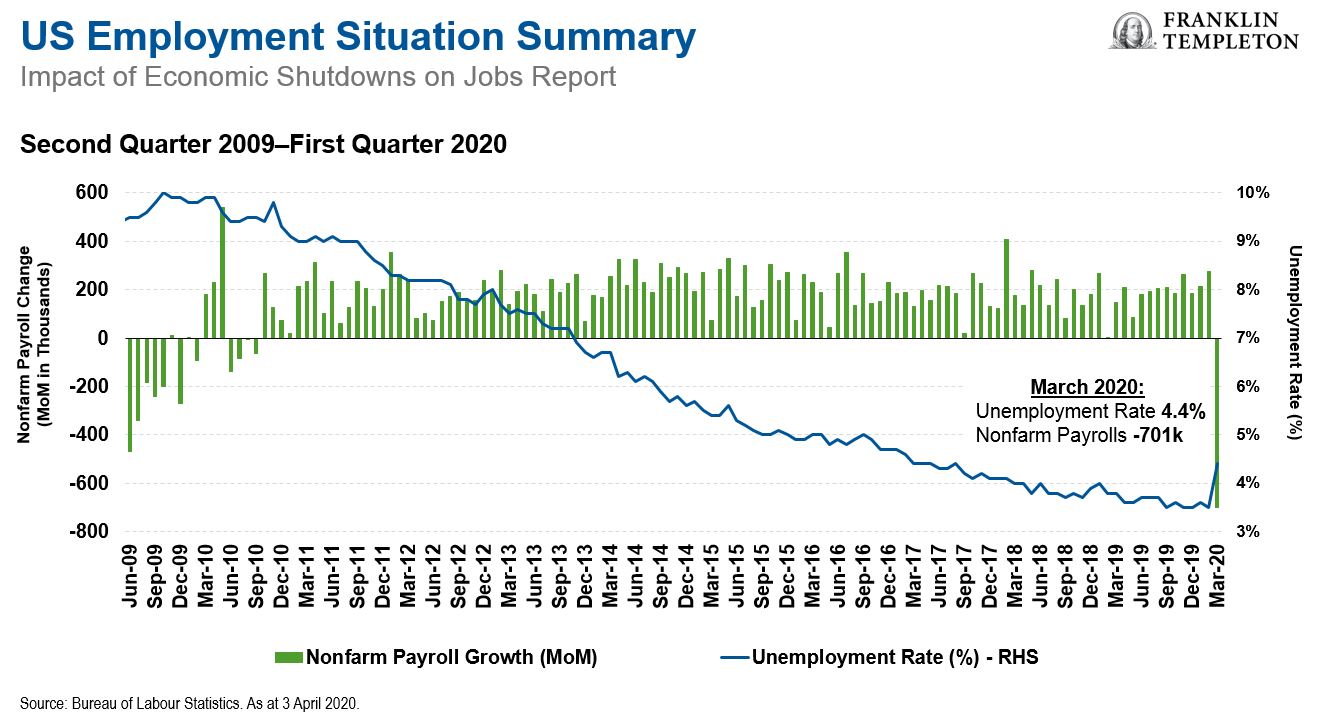

It is happening: US jobless claims went from almost nothing to about 10 million in the space of two weeks. Nonfarm payrolls plunged by 700,000 in March—they had been rising by almost 200,000 a month on average for the last 10 years. The US unemployment rate jumped from 3.5% to 4.4%—cue in the shocked chorus of analysts and media. The recession is here and the economy is now on life support.

But what kind of recession will this be, and what kind of recovery will follow?

I have seen countless comparisons to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Great Depression. Perhaps the COVID-19 recession will be as bad as 2009 or 1929, or even worse—but this time the scale of the recession is still partly within policymakers’ control. This is a very different recession—and understanding the difference is crucial to figure out how it will unfold.

This recession has not been triggered by an economic or a financial shock. It’s a recession by fiat—created by government decree much like a fiat currency. The US government has decided to shut down large parts of the economy overnight, instructing workers and consumers to stay home. This was the most prudent emergency move to halt contagion, but its massive economic and human costs are quickly becoming clear.

The key difference with the GFC lies in the underlying health of the economy. In 2009, the trigger was the unraveling of an enormous multi-layered credit bubble. The financial sector seized up and credit stopped flowing. Financial companies enacted massive layoffs; non-financial companies followed; this trickled down to shrinking demand for services. The recovery faced two major challenges: (i) how to repair banks’ balance sheets and get credit flowing again; and (ii) how to revive investment, employment and productivity in the right areas after the credit bubble had caused a massive misallocation of human capital and financial resources.

This time the banking sector is in good shape—indeed the government and the Federal Reserve (Fed) are relying on it to keep the economy alive while we fight the virus. Some companies are overleveraged following an extended period of record- low interest rates, but overall the non-financial corporate sector has proved resilient to a number of other shocks, from political uncertainty to protectionism.

The key difference with the Great Depression lies in the policy response. In 1929 there was none; in fact, the Fed contributed to the depth of the recession by tightening policy further even as the economy was falling off the cliff. This time the fiscal and monetary policy responses have been immediate, forceful, and well designed—building on the recent experience of fighting the GFC. The Fed has announced unlimited quantitative easing and new facilities to keep credit flowing where it is needed. Congress approved a US$2.2 trillion stimulus package to boost unemployment benefits and get cash to the households and businesses that need it—quickly, in a matter of weeks.

The devil is in the details, however, and execution is often harder than design. There will be frictions and hiccups as banks struggle to process massive numbers of new loans and government agencies struggle to channel help to a suddenly much larger number of people in need.

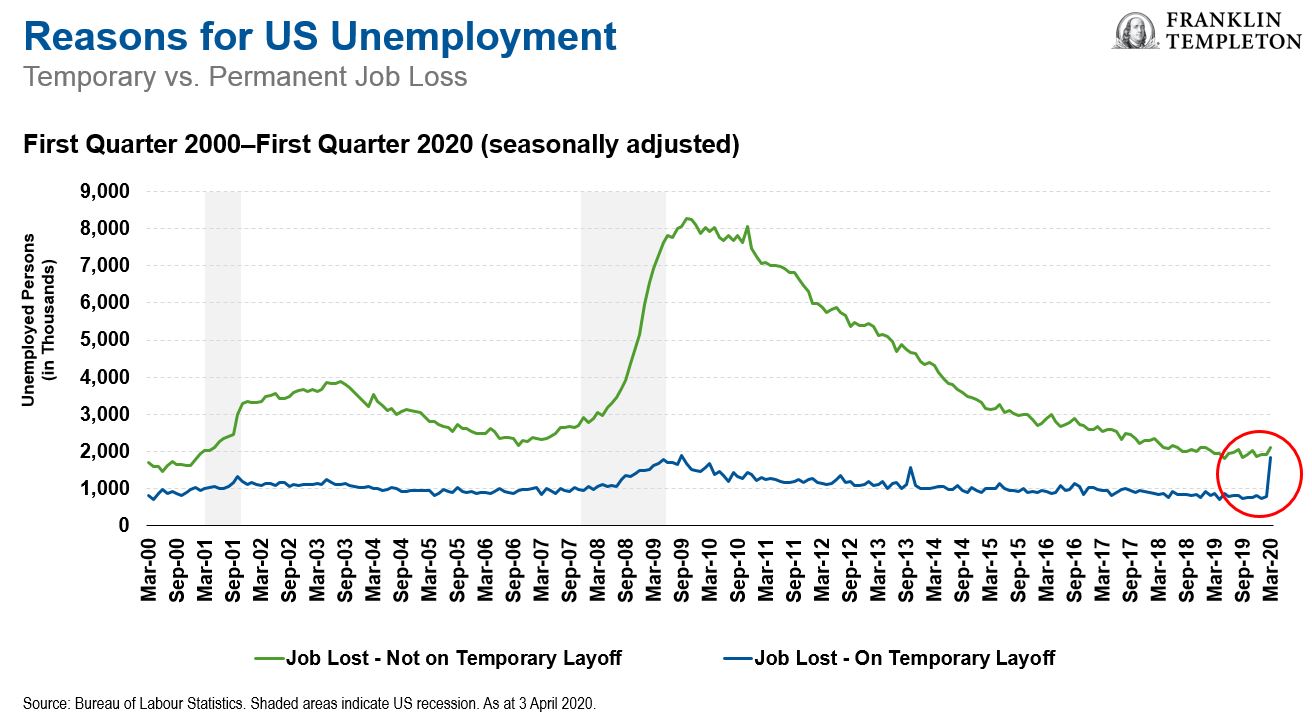

The latest US unemployment figures reflect the unusual nature of this recession. The number of people who reported being on temporary layoff jumped by 1 million in March, to a seasonally adjusted 1.8 million. Many employers clearly hope the shutdown will be brief, in which case it appears they intend to rehire their workers as soon as they can resume operating. Permanent job losses numbered “only” 177,000.

The jobless figures are staggering—but they should not be shocking.

The shutdown was the quickest way to halt contagion. But now the reality of it and the predictable magnitude of the human and economic consequences are beginning to hit home and need to be factored into the choice of the next steps. Thousands of small businesses are scrambling to figure out how they can survive. Millions of people are seeing their livelihoods suddenly destroyed. And let’s be clear, they are the most vulnerable: the workers who had only recently started to benefit from the tight labour market, the people with low or hourly wages and very limited savings.

Even a relatively short shutdown that accounts for government help puts this class of workers under very severe financial and personal stress. A longer shutdown could deal them a life-changing blow.

How deep this recession will be—and how difficult the recovery—depends on how long we keep the economy in this kind of artificially induced coma.

If we can gradually reopen the economy over the course of May, with some acceleration of activity in June, the damage could be limited, particularly if the government keeps providing support to households and businesses.

Most medical experts note that the health risk will disappear only when we have a vaccine or when enough of the population has been exposed and become immune. But social distancing prevents the latter, and developing a vaccine will likely take 18 months to two years, according to most experts.

We therefore face a difficult trade-off between health uncertainty and economic uncertainty. The longer we extend the shutdown, the more we understand about the virus (more time will give us more extensive testing which will give us better estimates of what share of the population has already been infected and of the true mortality rate), the more progress we can make on vaccines and therapies, and the more we can build up capacity in the hospitals. But a longer shutdown means more people will lose their jobs and more businesses will throw in the towel, with a greater loss of human and physical capital.

The longer the shutdown, the harder, slower and costlier the recovery. The CARES fiscal support package totals about 10% of US gross domestic product (GDP), and more will likely be needed; this year’s fiscal deficit was already projected to be about 5% of GDP, and the collapse in activity and tax revenues will make the overall deficit even larger. This is not the time to worry about rising public debt—but that time will come. The more we add to public debt and to the Fed’s balance sheet, the greater the risk that further down the line those imbalances will cause us another set of serious headaches.

Could we get into a new Great Depression scenario? The Great Depression started in 1929, reached bottom in 1933 and is widely considered to have lasted until 1939. A deep recession and deflation cut nominal GDP in half in short order; the consumer price index fell by nearly a third. Roosevelt’s New Deal helped stabilise the situation, but it took World War II and the post-war effort to pull us out of it. As I mentioned above, until Roosevelt stepped in, policy actually made the problem worse; Europe at the time was still reeling from World War I, with Germany still burdened by reparation payments; Asia’s economies played a secondary role.

Today’s policy response could not be more different, as policymakers across the world are providing policy stimulus; emerging Asia alone accounts for one-third of the global economy—and Asia is handling the COVID-19 crisis with much less disruption so far.

I think that expecting a repeat of the 2008-09 GFC, let alone the Great Depression, seems far-fetched.

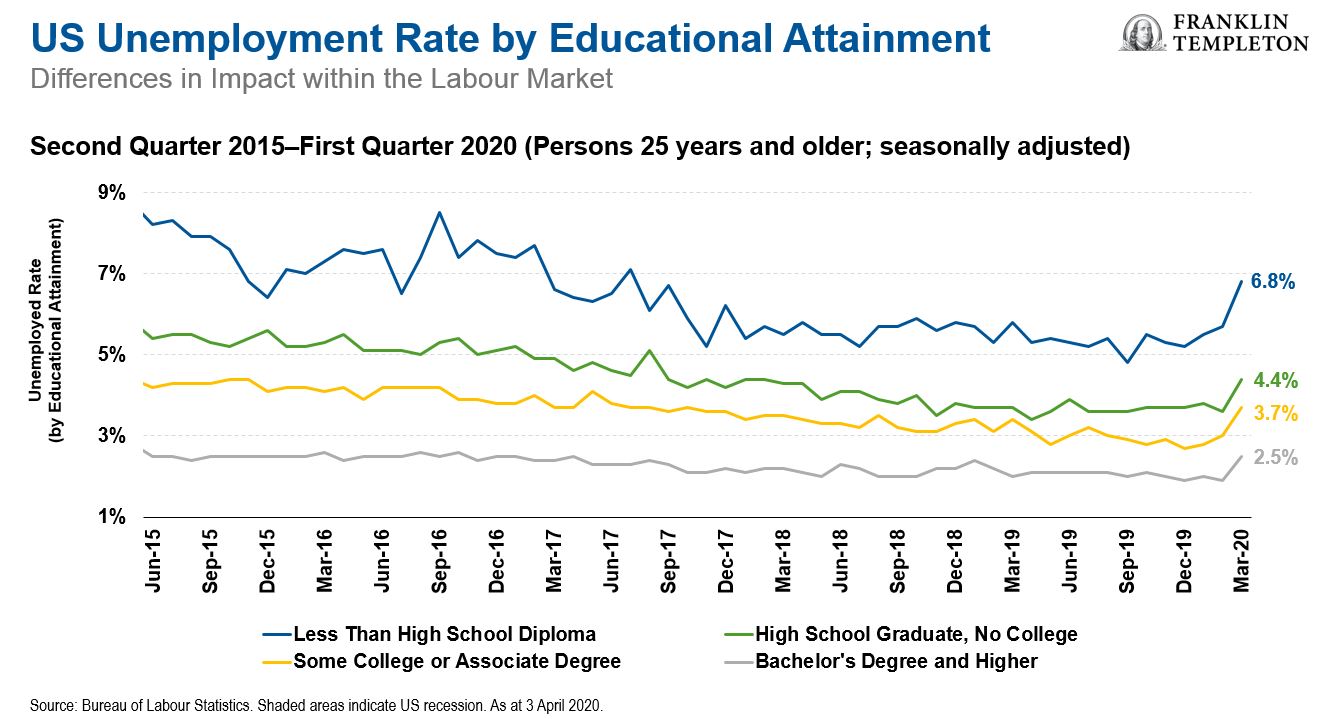

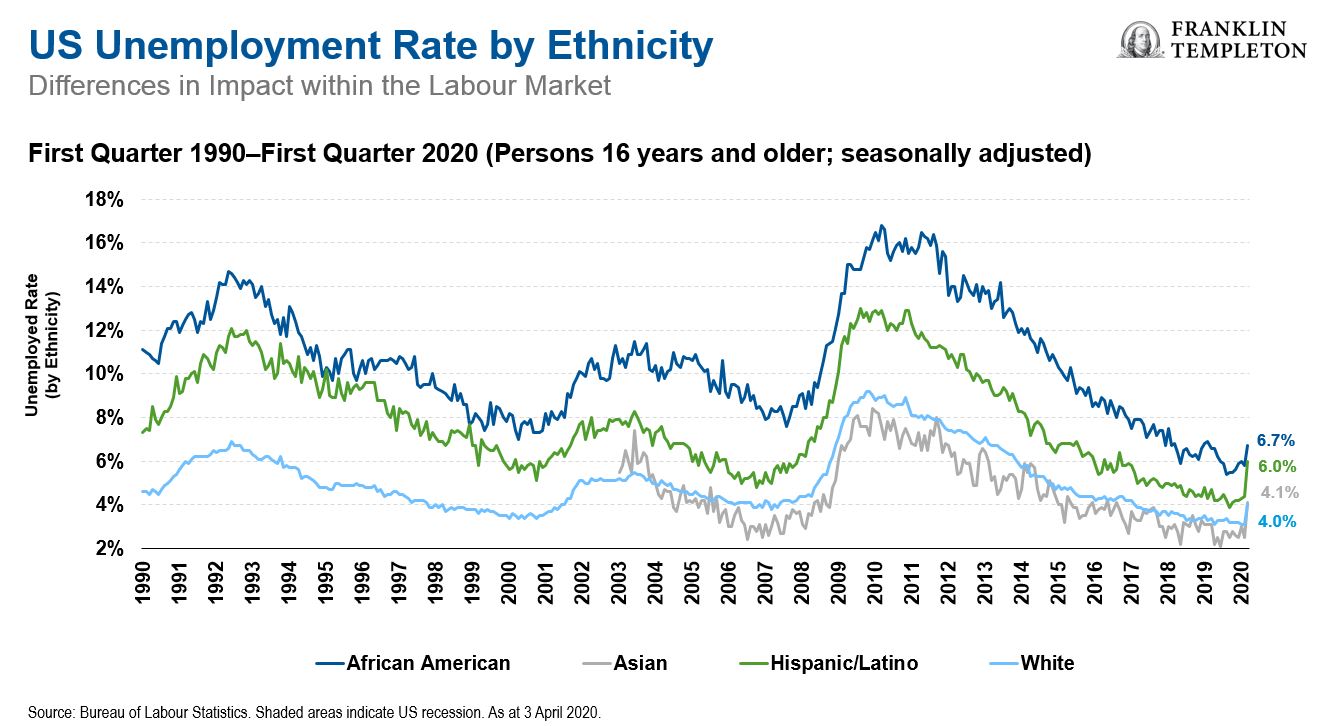

But the longer we extend this shutdown, the greater the risk of a severe and protracted downturn with massive adverse consequences on some of the most vulnerable segments of the population. Most white-collar workers, including in the financial sector, media and technology, continue to be able to work from home and draw a salary. Those who cannot are overwhelmingly blue collar.

Over the next two or three weeks, the priority should be to identify a strategy to restart economic activity while maintaining sufficient precautions to safeguard public health. If we wait much longer though, the recession will acquire its own momentum and our ability to engineer a recovery will be a lot more limited.

*****

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own professional adviser or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Templeton Distributors, Inc., One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com—Franklin Templeton Distributors, Inc. is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton’s U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Investments in foreign securities involve special risks including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments. Special risks are associated with foreign investing, including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments; investments in emerging markets involve heightened risks related to the same factors. Actively managed strategies could experience losses if the investment manager’s judgment about markets, interest rates or the attractiveness, relative values, liquidity or potential appreciation of particular investments made for a portfolio, proves to be incorrect. There can be no guarantee that an investment manager’s investment techniques or decisions will produce the desired result.

This post was first published at the official blog of Franklin Templeton Investments.