by Erin Bigley, AllianceBernstein

The most closely watched part of the US yield curve inverted this week for this first time since 2007, suggesting that a recession may be around the corner. We’re not convinced that’s true.

Don’t get us wrong, recession risks have increased over the last few quarters and investor caution is warranted. But while we expect the US and global economies to slow to their trend rate of growth, we’re not expecting contraction.

[backc url='https://sendy.advisoranalyst.com/w/J8pxsj3OgR4yxKxsA1169Q']And while risk assets sold off sharply following the inversion, it’s important to keep things in perspective. Prior to Wednesday’s selloff, the S&P 500 index had risen by more than 18% this year.

What Does Inversion Tell Us?

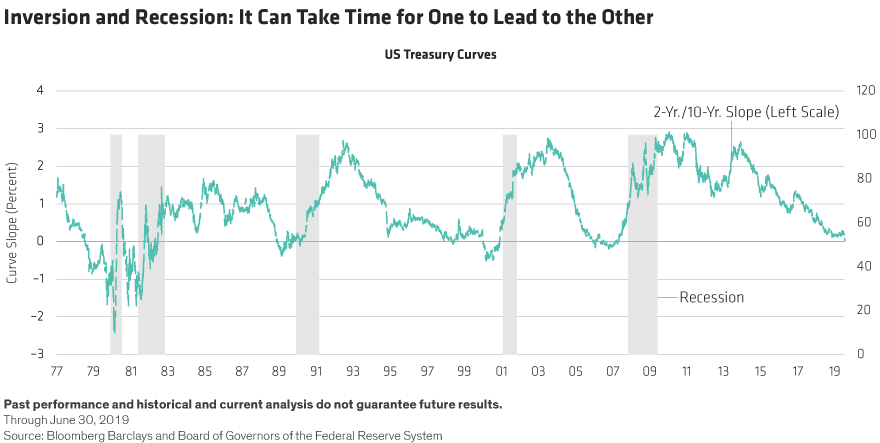

The steepness of the yield curve refers to the gap between long- and short-term Treasury yields, and that gap has been narrowing for some time. But markets took notice anew on Wednesday when the yield on the two-year Treasury note rose above that on the benchmark 10-year note. The gap between these two securities is the most monitored part of the curve for good reason: Inversion here has preceded every US recession over the past 45 years.

But here’s something to keep in mind: While the US has never had a recession that wasn’t preceded by an inverted yield curve, not every curve inversion has been followed by a recession. And even when inversion did lead to recession, there has often been a significant time lag between the two (Display).

Not Your Typical Inversion

Let’s consider why the curve inverted this week. What we’ve seen is a flight-to-quality by the vast numbers of global investors looking to take refuge in US Treasuries, one of the safest parts of the global financial market.

The anxiety stems from many sources: an escalating US–China trade war and the damage it may yet do to the global economy, unrest in Hong Kong and other factors. These are no doubt making investors more averse to risk. And with euro-zone and Japanese government bond yields in negative territory, there aren’t many alternatives to US Treasuries.

Interestingly, the flattening isn’t happening because the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates, pushing up the two-year yield and choking off economic growth. The Fed stopped hiking rates in 2018 and even delivered a rate cut in July, with more cuts expected.

The trade war is an important risk to monitor and it’s adding to market volatility, weighing on the global growth outlook (particularly for the Chinese and trade-sensitive euro-zone economies) and keeping monetary policymakers on their toes. But trade tensions and today’s other risks do not strike us as sufficient to tip the global economy into recession and drag the US—one of the stronger developed economies—down with it.

So, what makes us doubtful that a recession is imminent? A few things.

The US economy has slowed in recent quarters as last year’s fiscal tailwinds have faded. But the economic data still suggests growth, and consumers are still in good shape. Unemployment is below 4%, and falling interest rates should help by allowing consumers to refinance their mortgages and maintain spending.

The flattening we’ve seen in recent months may also be attributable to quantitative easing, which has distorted the long end of the curve. The Fed’s balance sheet is still many times its size in past cycles. And the effect of QE programs in other countries has probably boosted demand for US Treasuries, which helps to keep a lid on yields.

Taking a Wider View

The yield curve, while important, isn’t the only signal we watch when monitoring recession risk. Other signals are also important, including credits spreads—the extra yield corporate bonds offer over Treasuries. Another important signal is something we call “equity quality”—an indicator we use to judge whether corporate balance sheets are overextended.

These signals aren’t all pointing toward recession. Credit spreads are tight today, as they typically are late in a cycle. They’re not signaling distress, but investors need to be choosy.

In the case of corporate balance sheets, it’s true that corporate cash holdings have declined and net debt has risen. But this is being driven mostly by share buybacks, which return cash to shareholders and decrease net equity issuance—a positive sign for investors.

What about equity returns? History suggests yield-curve inversion has been a mixed signal. In the very short term, inversion has had a negative effect on equity returns. But average stock returns were negative only in the first month after an inversion. Further out, the average returns were positive.

Stay Active, Don’t Panic

The way we see it, this bolsters the case for taking an active approach to your portfolio and not following the herd. Worries always exist among investors, and today they apply all over the world: Brexit, trade tensions, unrest in Hong Kong and questions about monetary policy effectiveness. When anxiety is high, it’s easy to misread signals or miss opportunities. It’s one thing to be cautious, but quite another to allow panic to set in. The best investment opportunities often appear when emotions are driving the majority’s behavior and prices become detached from fundamentals.

While asset valuations aren’t cheap, they’re not significantly above historical averages. The S&P 500, for example, trades at 16.7x forecast earnings, only slightly above its long-term average.

On other measures, equities look relatively attractive. With the latest plunge in 10-year Treasury yields, the dividend yield on the S&P 500 exceeds the coupon on the 10-year note. Even so, investors should be careful about where they take their risk and feel confident they’re being adequately compensated for it.

An inverted yield curve is not the cause of a recession. Rather, it reflects the market’s view of how likely one is. That’s important to remember. With anxiety running high and the global political environment providing real reasons to be anxious, investors will keep worrying about recession risk. That will keep conditions volatile for the foreseeable future, but it doesn’t mean that markets won’t provide opportunities for good returns.

In our view, the greatest risk to the US and global economies is additional trade disruption. If trade tensions ease as the year winds down, market conditions should stabilize. But if that happens, it won’t happen quickly. The best approach in this environment? Be active, be cautious, and focus on your long-term plans and the investment mix most likely to achieve them.

Erin Bigley is a Senior Investment Strategist for Fixed Income at AB. Chris Marx is a Senior Investment Strategist for Equities at AB.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..