by Craig Basinger, Chris Kerlow, Derek Benedet, Alexander Tjiang, Gerald Cheng, RichardsonGMP

Sports betters and casino gamblers alike are always looking for that sure thing to move all in. With bond yields at the lowest level since 2017 and credit spreads the narrowest they’ve been since before the market melt- up in the fourth quarter last year (Chart 2 next page), fixed income investors may be wondering if they should begin taking their chips from the table.

Investing, however, isn’t gambling; the only free lunch is diversification. That “fix” or “free lunch” comes from combining uncorrelated assets into a diversified portfolio. This enhances risk-adjusted returns over the long term because as some investments rise, others fall (and vice versa). Through an inverse relation tried and tested through the years, equities and bonds have come to form the foundation of your standard balanced portfolio.

As both bonds and stocks continue to advance higher this year, recency bias has investors thinking that perhaps the inverse correlation is broken, thereby stoking fears that fixed income might not act as the sought-out safety net for investor portfolios during the next correction.

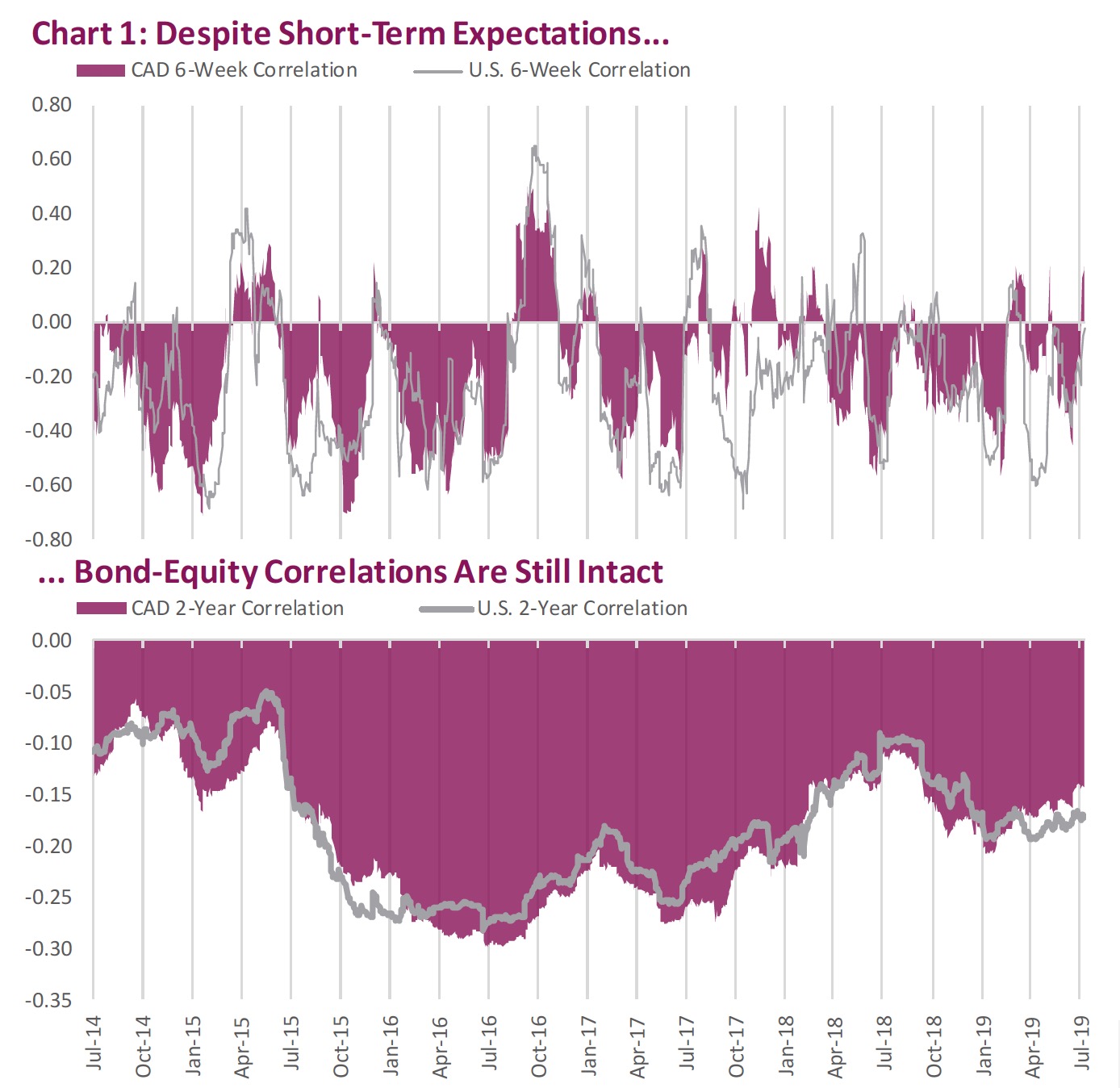

The reality is that the correlation hasn’t broken. The weekly correlation between the S&P TSX and the Canadian Bond Universe is -0.34 year to date. The story is similar south of the border: the U.S. has a YTD -0.46 weekly correlation between a similar broad market of domestic stocks and bonds. The relationship is not perfectly predictive in the short term, but over the long run it has held steadfast. Furthermore, the inverse relationship tends to be strongest during bouts of high volatility.

Chart 1 (on the first page) illustrates the rolling correlation between equities and bonds in both Canada and the U.S. over a six-week and two-year horizon. This shows that over some brief periods, equities and bonds can move in tandem but over a longer period they tend to move in opposite directions.

Consider the equities drawdown we experienced in May, when the S&P 500 fell 6.4% and the U.S. aggregate bond market edged higher by 1.7%. We saw the same thing in December when the same U.S. index fell 9.3% and bonds rose 1.5%. Despite yields at recent lows, traditional bonds still offer diversification benefits.

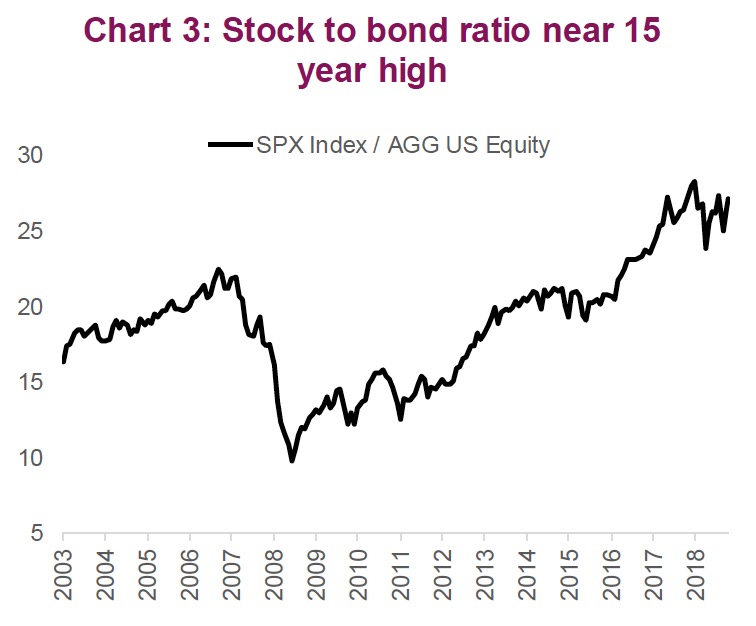

Naysayers may continue to disagree and continue betting on what’s working now. The stock-to-bond ratio remains near 15-year highs, though it has been a slight tug of war between bond and stocks over the past couple of years (Chart 3). Moreover, even those who believe in the math and employ diversification in an investment management strategy, tend to wrestle with the thought of buying boring bonds.

Many of those who have held a meaningful fixed income weight tend to be leaning towards bonds with more credit exposure to chase higher yields or move into fixed income alternatives, which tend to have higher correlations to equities, particularly during bouts of volatility.

Perhaps what has most intrigued us, is the momentous shift into passive fixed income ETFs (Chart 4). Increasingly ETFs are grabbing the lion’s share of fixed income fund flows. The main advantages of these instruments range from their ease of use, more accessible liquidity, less onerous capital requirements and, most importantly, lower costs.

Passive fixed income certainly has a place in a portfolio, as it provides the investor with the ability to make swift tactical asset-allocation changes while reducing fee drags. But this financial innovation comes with some drawbacks not discussed in most sales literature.

For context, let’s consider a passive market-weighted equity ETF which must allocate progressively larger pools of its funds into – as you would imagine – the largest companies in the universe.

In the S&P 500, for example, Microsoft, Apple and Amazon rank high among the best- performing companies in recent memory and hold market leadership positions in several categories. As investors reward such qualities, these companies have “earned” the right to be some of the index’s largest members.

Alternatively, the way a company becomes a bigger part of a fixed income index is by issuing more debt. Holders of a passive fixed income ETF that tracks an underlying bond index therefore end up receiving a growing share of debt issued by companies that are most aggressive in levering up their balance sheet.

To illustrate this point, consider that the top four ex-financial firms in the U.S. Investment Grade Bond Index have increased debt by 2.11x over the past seven years and now account for over 10% of the index (Chart 5). Suddenly, bonds aren’t that boring anymore.

Another major difference between most fixed income ETFs and the bonds held therein is that a holder of an ETF does not get any money back until they liquidate their position. If one were to buy a basket – or ladder – of bonds from a variety of issuers, they would receive the entire principal plus interest earned upon each security’s maturity.

With a traditional ETF, profits only pay out interest after expenses. However, the investor must nonetheless ride the wave of volatility caused by changes in bond yields, convexity and credit spreads. The financial jargon is probably as clear as a muddy puddle for some, so consider an example.

Say you are an older investor with $2 million to buy a retirement home in five years. You can tolerate medium risk and decide to put half in stocks and half in bonds. You can make it easy and buy a million dollars of ZAG, the largest Canadian fixed income ETF, for a cost of just 9 basis points. Or you can buy a basket of bonds that mature in five years.

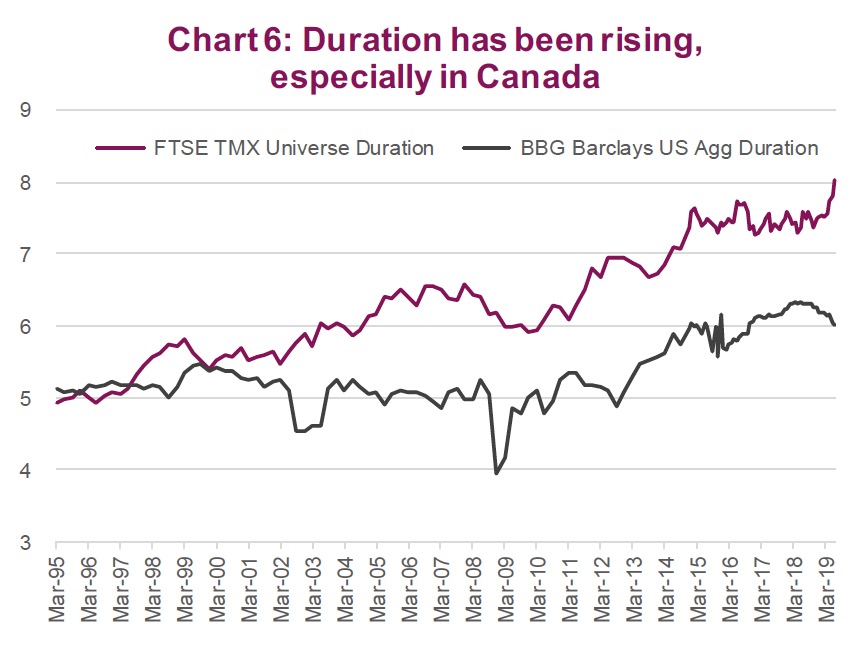

In five years from now, say bond yields rise 2%, the price of ZAG may drop around 16% based on its duration of 8 years (Chart 6). The price of the ETF could fall further if credit spreads move higher. Conversely, the individual bond investor will simply recoup their million dollars. Both still earn interest along the way.

If you or your clients do not have a liquidity need at a specific date, a ladder strategy can have a similar outcome, generating income for the investor every time a bond matures, to be reinvested in another longer-dated bond. The finance world is constantly evolving, and one recent development in the ETF space has sought to replicate some of these benefits:

Target maturity bond ETFs hold a basket of bonds that mature in the same year. Once the bonds in the fund mature, the fund is closed, and the investor is paid out.

Like passive fixed income ETFs, direct bond investing has its own limitations. It usually only makes sense for mass affluent investors who plan on holding the bonds to maturity.

Why? Because some bonds tend to have mark ups and wide bid/ask spreads. This is more jargon, but the point is that fees increase the smaller the purchase and the more frequently the asset is traded. Additionally, certain bonds outside of money market, government and high-rated investment-grade paper offer poor liquidity; unlike stocks, some of these bonds only trade weekly or monthly.

Both traditional bonds and passive ETFs have their unique pros and cons. If you’re planning for a long-term commitment or have a specific goal in mind, buying individual bonds provides the highest level of safety for your principal and the ability to weather changes in the interest rate environment.

Alternatively, ETFs provide an extremely liquid and cost-efficient way to benefit from the portfolio diversification that bonds deliver. ETFs also allow you to easily add to your investments or tactically change duration and alter credit exposure. Investors have individual goals and objectives, and it’s important to carefully establish those specific objectives in order to develop an optimal solution.

Source: All charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P. and Richardson GMP unless otherwise stated.

This publication is intended to provide general information and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any securities. Past performance of securities is no guarantee of future results. While effort has been made to compile this publication from sources believed to be reliable at the time of publishing, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to this publication’s accuracy or completeness. The opinions, estimates and projections in this publication may change at any time based on market and other conditions, and are provided in good faith but without legal responsibility. This publication does not have regard to the circumstances or needs of any specific person who may read it and should not be considered specific financial or tax advice. Before acting on any of the information in this publication, please consult your financial advisor. Richardson GMP Limited is not liable for any errors or omissions contained in this publication, or for any loss or damage arising from any use or reliance on it. Richardson GMP Limited may as agent buy and sell securities mentioned in this publication, including options, futures or other derivative instruments based on them. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trademark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trademark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited. ©Copyright July 15, 2019. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Richardson GMP