by Brian Levitt, Invesco Canada

Kristina: As of July 1, the U.S. business cycle has set a new record for longevity. It’s a significant milestone, to be sure, but what does it really mean for investors? The answer might not be what you think. To help put this cycle into context, I’m turning over this edition of Weekly Market Compass to my colleague Brian Levitt, Global Market Strategist for North America.

Longevity doesn’t equal strength

Brian: It’s official! The U.S. business cycle, on its 3,682nd day, has now surpassed the elongated cycle of 1992-2000.1 This cycle has now been going on for longer than The Beatles were together. It has persisted for a more extended stretch than the original run of Seinfeld on network TV. It’s older than Instagram.

While much may be made of this record-breaking day (or not), the age of the cycle, in and of itself, doesn’t really tell us much, just as the age of a human being doesn’t necessarily provide information on the health or productivity of that human being. As an example, consider the careers of The Beatles and their fellow British Invasion band, Herman’s Hermits. The former produced 27 No. 1 hits in eight years, while the latter produced two No. 1 singles in 55 years. The point is that simply knowing the duration of a cycle (or a music career) tells you little about the total output.

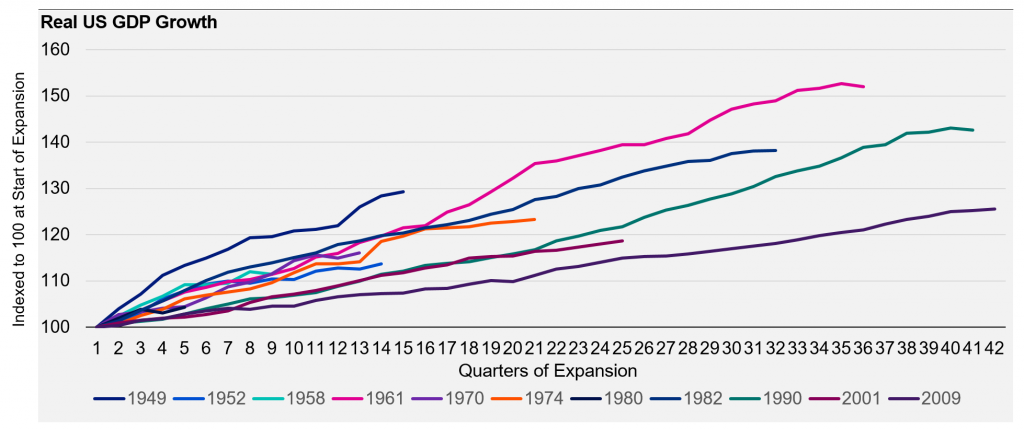

How does the output of this cycle compare to that of prior cycles? Despite being the longest on record, the current business cycle has the indignity of being the weakest cycle in the post-World War II period. The cumulative growth over the full period is approximately 20%, or roughly 2% per year; bringing U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) up from $15.8 trillion in 2007 to $18.9 trillion today.2 Each of the other cycles that had surpassed 20% cumulative growth in real GDP (the cycles beginning in 1949, 1961, 1974, 1982 and 1990) did so on average over 16 quarters — not over 10 years.3

Duration and magnitude of post-WWII U.S. cycles

Source: Bloomberg, L.P., June 30, 2019. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

The end is near … or is it?

Many investors may reason that the record-setting cycle must be coming to an end soon. After all, as the father of English literature, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote in 1386, “All good things must come to an end.” Fortunately, cycles don’t end simply because they were “good” or because they have aged. Instead, recessions have been the result of significant excess and failed policy.

So where does that leave the U.S. today? In my view, the current open-ended policy environment of modest growth and modest inflation is likely to keep the Federal Reserve at bay indefinitely, which could extend the cycle for longer than most expect. As for excesses, let’s compare the current environment to those that preceded the more-spectacular cycle endings over the past century.

- Banking crisis of 1929: On the eve of the Great Depression, bank credit had grown 20.9% over the prior year, compared to the current rate of 5.6% and the long-term average of 7%.4

- Stagflation of 1980: By early 1980, inflation had climbed 14.8% over the prior year, and the Federal Reserve was raising rates rapidly.5 Currently, inflation is sub-2% and inflation expectations are falling.6 The Fed, for its part, has signaled that the next interest rate move may likely be a cut.

- Tech bubble of 2000: By the late 1990s, stocks were trading at nearly 30x the prior year’s earnings.7 Stocks were not only expensive compared to their own history but also trading excessively rich compared to all other asset classes. Currently, stocks, which have been trading at 19x last year’s earnings, are moderately rich compared to their history but cheap compared to bonds.8

- Housing crisis of 2008: By 2008, U.S. households had compiled debt that was equal to 132% of their disposable personal incomes (DPI), with mortgage debt representing 100% of DPI.9 Following a prolonged deleveraging period, U.S. household debt equaled 98% of DPI at the end of 2018, and has still been falling, with mortgage debt representing only 66% of DPI.10

In my view, the lack of excesses suggests that barring a major policy mistake, the current cycle likely has more room to run and more duration records to break. To cautious investors watching as the economic cycle breaks new records and the markets hit new highs, I say that it is likely not too late to participate. As Chaucer said, “Time and tide wait for no (wo)man.”

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog