by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Franklin Templeton Investments

Last week we held our annual Global Investment Forum in San Francisco. It’s always a great opportunity to share with our clients our view of the global economic outlook and asset markets, and to learn together from top business and thought leaders joining us as external speakers.

For our 2019 forum we chose tech and innovation as the leading theme, and the speaker lineup featured a number of luminaries, including Adobe Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Shantanu Narayen, Workday CEO Aneel Bhusri and PayPal CEO Daniel Schulman.

We are very focused on fintech, like many firms in our industry, and Franklin Templeton Fixed Income is bolstering the role of data science and analytics—more on that in a future post. In this forum, though, we wanted to explore the broader impact that technological innovations will have on the economy, and on our personal and professional lives. I want to share some of the key takeaways and a few of my reflections.

First, the speed of change is dizzying, and it poses a tough challenge to corporate strategies. I know that “the pace of innovation keeps accelerating” has become a cliché. But when you are reminded of how quickly computing power keeps improving (yes, Moore’s Law is breaking down, but quantum computing is on the horizon),1 and how fast the cost of storing, processing and transmitting data is falling, you realise that the reason it’s a cliché is because it’s true.

An even more powerful statistic, in my view: the average lifespan of a Fortune 500 company has fallen from about 70 years to just over 10 years. Let that sink in because it’s sobering: Even if you’re one of the most successful companies, your average life expectancy barely exceeds 10 years. Innovation disrupts the competitive landscape, and adapting strategy is not easy. Shantanu Narayen recounted how he led Adobe to switch to a cloud-based subscription model so as to deliver faster innovation on the company’s suite of products; even just explaining how the sudden reduction in short-term revenues would pay off in higher recurrent revenues down the line was a tricky challenge.

Our analysts who follow the corporate sector have an even tougher job—understanding the fundamental strength of each company, including its ability to evolve successfully in a changing environment, is more important than ever.

Second, the impact of innovation on productivity, economic growth and global trade will be more profound than most people realise. I noted in my last article how technological innovations have already spurred the rise of local supply chains, so that the elasticity of global economic growth to global trade is a lot lower than it used to be. This is an example in which the powerful effect of innovation on economic trends is already plain to see.

There will be more. So far, the impact on productivity has been limited, and economists are still arguing about why this boom in innovation has coincided with a slump in productivity: The rate of productivity growth in the United States fell from an average of 3% during 1996–2005 to just 0.8% in 2011–2018. A similar deceleration has occurred in most other advanced economies.

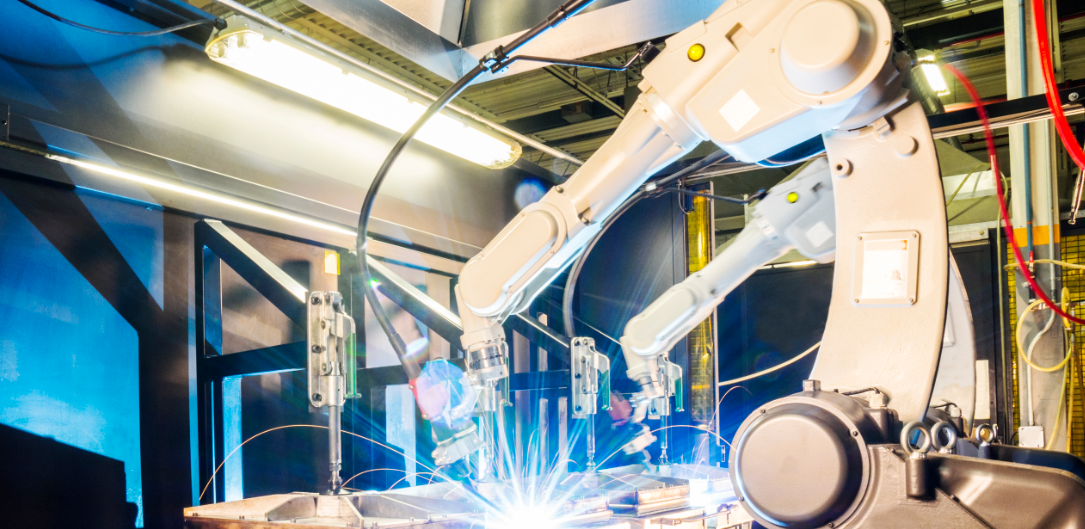

But productivity growth has just begun to pick up, and now the advent of 5G networks will accelerate the development of the so-called Internet of Things and, more to the point, the Industrial Internet of Things (i.e., a world where most industrial machines will have high-powered computing capabilities embedded in them). The same will be true for cars, streetlights, and many other objects that we encounter in our everyday life. The speed of 5G will enable all these machines and devices which reside “at the edge” of the network to communicate with cloud-based artificial intelligence (AI) systems extremely quickly, reducing latency—and since the computing can then be done in the cloud, every machine can become “intelligent” without the need to embed a super powerful computer in its own hardware.

Yes, it will take more time for these innovations to scale. It will take time for the new intelligent machines of the Internet of Things to be incorporated in the capital stock through new investment, for companies to adapt their operations and management practices to make best use of these new capabilities, and to upgrade the skills of the workforce. But if you don’t think these innovations will boost productivity, think again. If investment remains robust, I believe we are headed for much faster productivity growth and stronger economic growth, and all the talk of “secular stagnation” will quietly die away.

Faster productivity growth would also undermine current arguments that the natural real rate of interest will forever be a lot lower than it used to be—another reason why I think long duration2 is not a good investment choice for us at this point.

Third, data are your biggest asset and your toughest challenge. PayPal’s CEO Daniel Schulman rolled off an impressive series of statistics: over 80 trillion emails sent in 2018, 5 trillion of which carried a virus; 10 billion of Facebook/WhatsApp messages sent every day; 1 billion tweets every day (and 1.4 billion Tinder swipes!).

As data transmission and storage get cheaper, we generate and collect more and more data. More data enables smarter choices, but only if you can separate signal from noise, which as the quantity of data rises exponentially becomes a lot harder. Machine learning can be a powerful ally here, but it needs to be complemented by human expertise.

This ongoing data revolution has two other important dimensions that are relevant for investors. One is privacy and data ownership. The debate on privacy and regulation has just started; it will go far beyond social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, impacting health care and other economic sectors. How rules and regulations on privacy and data ownership evolve will have an important impact on business models and investment decisions. The other, related dimension is cybersecurity. This will have a growing impact in business strategies, investment risk assessments and geopolitical developments.

Fourth, the impact on jobs and incomes will be a lot more nuanced than the headlines suggest. The prevailing view is that we are headed for mass automation and widespread unemployment—and fast. Economic studies have captured the headlines with large estimates of jobs that will likely be displaced by automation.3 The factory of the future will have only two employees: a human and a dog. The human’s job will be to feed the dog; the dog’s job will be to make sure the human doesn’t touch anything…

So goes the joke. Yet the numbers tell a different story. Employment keeps climbing to new record highs: The United States today has 10 million jobs more than at the previous peak of employment before the 2009 recession, and the unemployment rate has fallen to a 50-year low.

Does that mean we have nothing to worry about? No. The rapid pace of innovation requires different skills in the workforce, and current evidence of significant skills gaps in manufacturing suggests we are not doing very well on this front. We need to do a much better job at understanding the complementarity between humans and machines to ensure that innovation results not just in more jobs, but in better jobs that can command higher wages—and in higher productivity.

For us as investors, all this has several important implications:

- First, in this data-abundant world, AI is a powerful new tool but not a panacea. Advanced data science capabilities are becoming essential for a successful investment strategy, but you need to bring together deep investment expertise with deep analytics know-how to apply them effectively. Data science could easily lead you astray if you don’t have a strong grasp of the data science, the business problem you are trying to solve, and the economic and market fundamentals you are trying to assess.

- Second, attention to company-, industry- and country-specific fundamentals is more important than ever. Innovation has already started to disrupt companies and industries at an unprecedented speed, and to upset the traditional competitive balance across countries.

- Third, we need to look at the macro environment in a different way. Innovation has already transformed the nature of global trade. We are barely beginning to understand the implications for skills, jobs and incomes—which will be reflected in savings and investment trends.

- Finally, when we look at innovation we should believe in its potential, but not buy into the hype. The impact of this new wave of innovation will be profound and disruptive. But it will take time for the full impact to unfold—longer than the hype suggests.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Investing in fast-growing industries, including the technology sector (which has historically been volatile) could result in increased price fluctuation, especially over the short term, due to short product cycles, falling prices and profits, competition from new market entrants and development and changes in government regulation of companies emphasising scientific or technological advancement as well as general economic conditions. Growth stock prices reflect projections of future earnings or revenues, and can, therefore, fall dramatically if the company fails to meet those projections.

Important Legal Information

The companies and case studies shown herein are used solely for illustrative purposes; any investment may or may not be currently held by any portfolio advised by Franklin Templeton Investments. The opinions are intended solely to provide insight into how securities are analysed. The information provided is not a recommendation or individual investment advice for any particular security, strategy, or investment product and is not an indication of the trading intent of any Franklin Templeton managed portfolio. This is not a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any industry, security or investment and should not be viewed as an investment recommendation. This is intended to provide insight into the portfolio selection and research process. Factual statements are taken from sources considered reliable, but have not been independently verified for completeness or accuracy. These opinions may not be relied upon as investment advice or as an offer for any particular security. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton Investments (“FTI”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FTI accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

To get insights from Franklin Templeton delivered to your inbox, subscribe to the Beyond Bulls & Bears blog.

For timely investing tidbits, follow us on Twitter @FTI_Global and on LinkedIn.

________________________________________________

1. Moore’s Law refers to the observation made in 1965 by Gordon Moore that the number of transistors per square inch on integrated circuits had doubled every year since the invention of the integrated circuit. The current definition of Moore’s Law holds that data density doubles approximately every 18 months.

2. Duration is a measure of the sensitivity of the price (the value of principal) of a fixed-income investment to a change in interest rates. Duration is expressed as a number of years.

3. A 2013 Oxford University study estimated that 47% of existing US jobs are at high risk of automation (Frey and Osborne, “The Future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization?”).

Copyright © Franklin Templeton Investments