by Craig Basinger, Derek Benedet, Chris Kerlow, Alexander Tjiang, RichardsonGMP

There is an evolution for individuals learning to play poker that is often captured in the adage ‘Play the player, not your cards’. Beginning players will often solely focus on the cards they are dealt and the chances of improving on the subsequent reveal of communal cards (Texas Hold’em style). As skill advances, players will start giving increased consideration to what their opponents have and how they react to new cards, then advance to consider what do their opponents think that they have.

We believe this evolution of thinking has similarities to incorporating behavioural finance into an investment process. Initially, you are looking at a potential investment on its own merits. Valuations, growth prospects, quality of management, fancy new doohickey, business risks and opportunities, etc. This is ‘playing the cards’. But with investing, as is with poker, your opponent matters just as much. After all, if you believe an investment is a good idea and worth inclusion into your portfolio, there is someone on the other side of that trade selling to you. Do they know more or less than you? Do you have an analytical advantage? Are they as emotionally sound in their decision to sell shares to you? Where is your edge coming from?

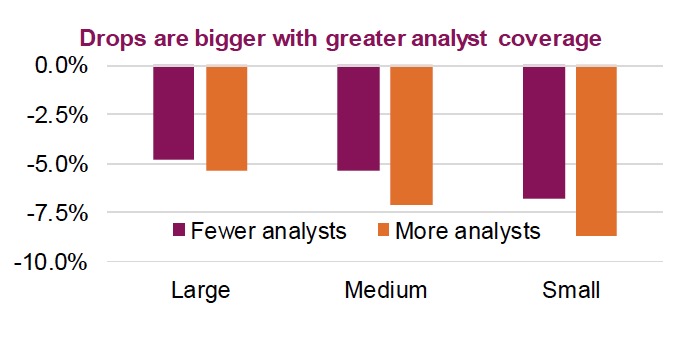

Becoming a behavioural investor requires you to not just rely on a sound fundamental investment approach, but to incorporate the behaviour of other market participants into your process. Understand when you are being emotional, which raises the probability of a mistake. Understand when other market participants, aka the other side of trades, are being emotional. Or for you poker players: when other market participants are ‘on tilt’.

The speed of news

Today, news travels fast. There was a time long ago when news of an event somewhere around the world would take hours or days to reach you. Today, news of an event is almost instantaneous and quickly includes not just text but pictures and video. The financial world is no different: it’s fast and everyone gets it at the same time. Thanks to regulation FD (fair disclosure), company news is regulated to be released uniformly. No more little hints from corporate executives to their favorite analysts or friends. If material news is involved, it must be broadcast that everyone has access at the same time. If you wanted a scenario that likely causes some investors go ‘on tilt’, this may be it, with everyone scrambling to update their opinion/valuation/view on a company at the same time absorbing new information. Understanding nuances in how news is absorbed can give you an edge, when others are more likely to over or under react.

While news is fast and largely uniform, how news is absorbed to update existing views and perceptions is not. We analyzed the S&P 1500 constituents over the past five years looking at all instances when a company’s share price opened the next day outside two standard deviations of that company’s historical daily volatility. With about 15,000 instances, we analyzed how prices react and find a new equilibrium. Essentially how investors react and absorb the news. Some things we found were not surprising, some were.

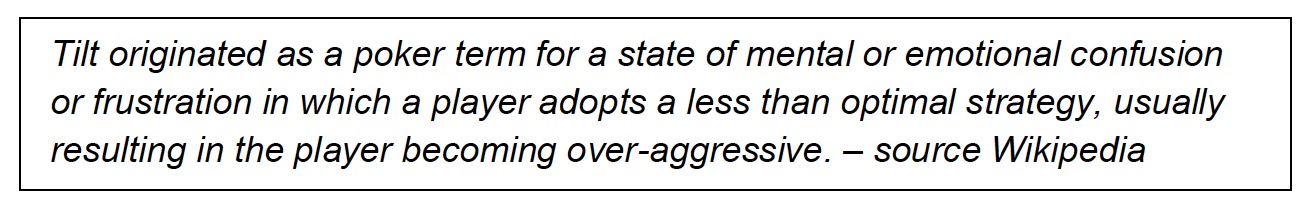

There is a relationship between company size, volatility and reaction to news. Not surprising, smaller companies measured by market capitalization experience bigger pops on good news and bigger drops on bad news relative to larger companies. Yes, more evidence that smaller cap companies are more volatile than larger cap. Of greater insight, investors appear to overreact to bad news but incorporate good news rather quickly and more accurately. The top chart is the average performance following the initial pop or drop, adjusted to be relative to the market (note EOD is end of day and days are measured in trading days).

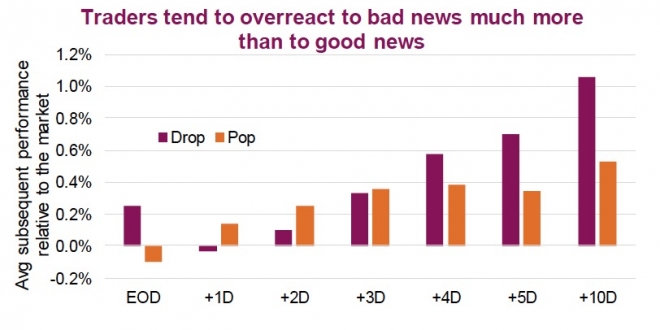

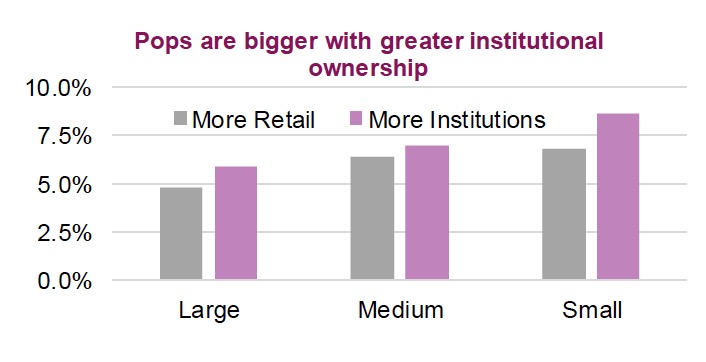

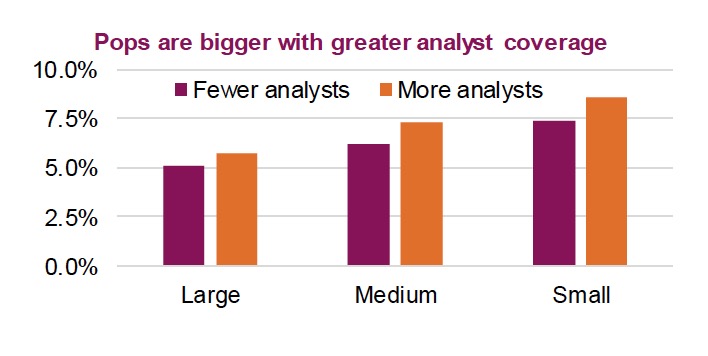

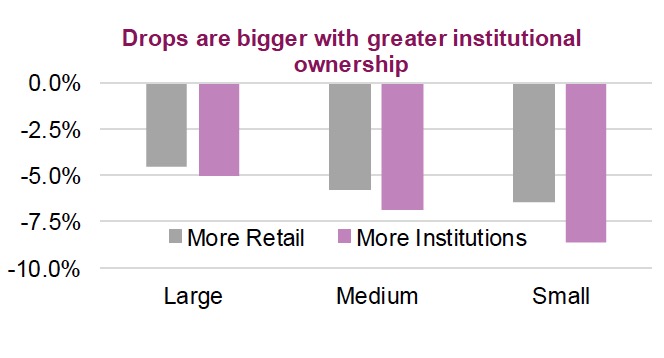

Given the strong relationship between volatility and company size, we isolated size by breaking all instances into four quartiles called Large, Medium, Small and Tiny. Across all size categories, there was a positive relationship between the magnitude of the pop or drop and both the number of analysts covering a company and percentage of institutional ownership. In other words, companies with greater analyst coverage or a higher portion of institutions in their shareholder base seems to experience larger moves on news. (charts 2, 3, 4, 5)

One likely reason for this is the relative speed at which investors update their opinion on the company after the market moving news. Institutional investors would adjust quickly, updating their valuation models likely before the market opens the next day. Sell-side analysts would be doing the same and share their updated views with clients. For the most part, Non- institutional investors (aka retail) probably don’t update their opinions on a company that reported after the close on a Wednesday before the market opens Thursday morning. As a result, companies with more of a retail investor base and/or fewer analysts covering the name, tend to have a more muted reaction to both good or bad news.

Bad news travels faster

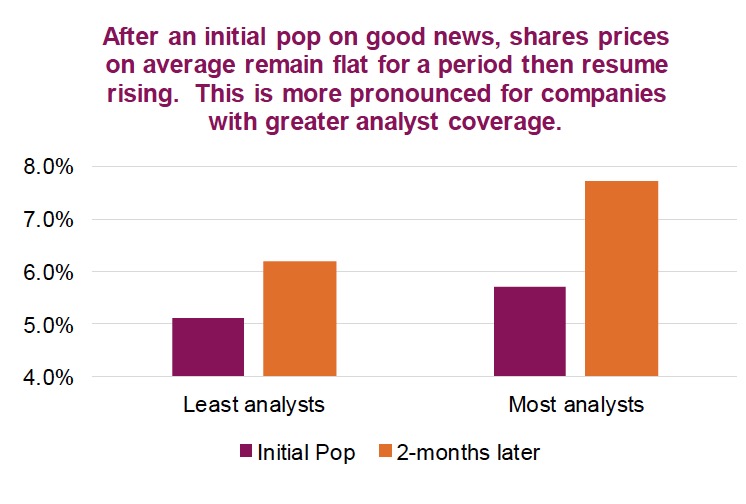

While it does appear that market participants tend to overreact to bad news (perhaps as a knee jerk reaction or due to other traders chasing short term momentum [HFT]) over the subsequent days or weeks a new equilibrium appears to be reached. On average. This appears evident regardless of institutional ownership or differences in analyst coverage. Good news on the other hand appears to have a more lasting residual impact, especially for companies with lots of analyst coverage.

We found that after a positive pop on good news, share prices on average tend to remain flat for a period then begin rising again. Even adjusting for the market move, this appears to be evident. The rise does appear more pronounced for companies with more analysts covering them. Companies tend to experience a fall in the number of buy recommendations following a bad news drops and an increase in buy ratings after a good news pops. Perhaps some of this residual move to the upside is attributable to analysts updating their views following good news and raising their recommendations.

Investor takeaways

While this ethos may appear a bit abstract, trying to understand how other investors and the market is most likely to react to news can give you an edge. At the very least an additional input into an investment process. Here are a few takeaways for consideration:

• At the open, the market often overreacts to bad news. This can create opportunities but clearly you need to be fast. • Good news does not seem to cause a price overreaction in the short term. However, for companies with more analysts covering them, there appears to be a stronger residual lift in the months ahead.

• Greater institutional share ownership and/or greater analyst coverage appears to increase the magnitude of an initial price reaction to both good or bad news.

• In the month following a big price drop, a company is more likely to see analysts reduce their recommendations. Big price pop often precedes analysts increasing buy ratings.

This publication is intended to provide general information and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any securities. Past performance of securities is no guarantee of future results. While effort has been made to compile this publication from sources believed to be reliable at the time of publishing, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to this publication’s accuracy or completeness. The opinions, estimates and projections in this publication may change at any time based on market and other conditions, and are provided in good faith but without legal responsibility. This publication does not have regard to the circumstances or needs of any specific person who may read it and should not be considered specific financial or tax advice. Before acting on any of the information in this publication, please consult your financial advisor. Richardson GMP Limited is not liable for any errors or omissions contained in this publication, or for any loss or damage arising from any use or reliance on it. Richardson GMP Limited may as agent buy and sell securities mentioned in this publication, including options, futures or other derivative instruments based on them.

Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.

RichardsonGMP © Copyright 2019. All rights reserved.