by Arnab Das, Global Market Strategist, EMEA, Invesco Ltd., Invesco Canada

On Tuesday, Parliament rejected U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit Withdrawal Bill by a 230-vote margin – the largest defeat of legislation in nearly 250 years, when Parliamentary records began.† That the defeat exceeded consensus by as much as 100 votes reflects the depth and breadth of dissatisfaction with May’s Brexit plan. Many Members of Parliament (MPs) fear it could further undermine the economy, contribute to secession in Northern Ireland or Scotland, or might not confer the freedom for which Brexiters campaigned in the referendum.

The immediate next step was a no-confidence motion against the May government, which she survived January 16 by a vote of 325 to 306. Now, we expect something of a return to the Brexit drawing board, with a continuum of potential outcomes from a no-deal “Brexident,” to a softer version of Brexit, to even cancelling Brexit and staying in the EU. Both the U.K. short- and long-run economic outlook hinge on how Brexit is ultimately executed – if at all.

What are the odds of each scenario?

The plethora of issues in the U.K.’s contentious relationship with the EU boils down to membership of the EU’s Single Market (SM) and Customs Union (CU). The SM comprises four freedoms – free movement of goods, services, people and capital. Continued membership would be highly desirable for services trade in which the U.K. is a world leader and enjoys sizable services trade surpluses, including with the rest of the EU. But continued membership would require free EU migration, the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and contributions to the EU budget. Rejection of these three key items is seen as the main motivation behind the 2016 Brexit referendum result in which 52% of participants voted to leave the EU.

The CU is highly desirable for goods trade, but requires abiding by the EU’s common external tariffs and regulations, disallowing free trade agreements with other countries. The U.K.’s legal treaty commitments to Ireland and political commitments to Northern Ireland are tantamount to avoiding a hard border on the island of Ireland, which would require remaining in the CU.

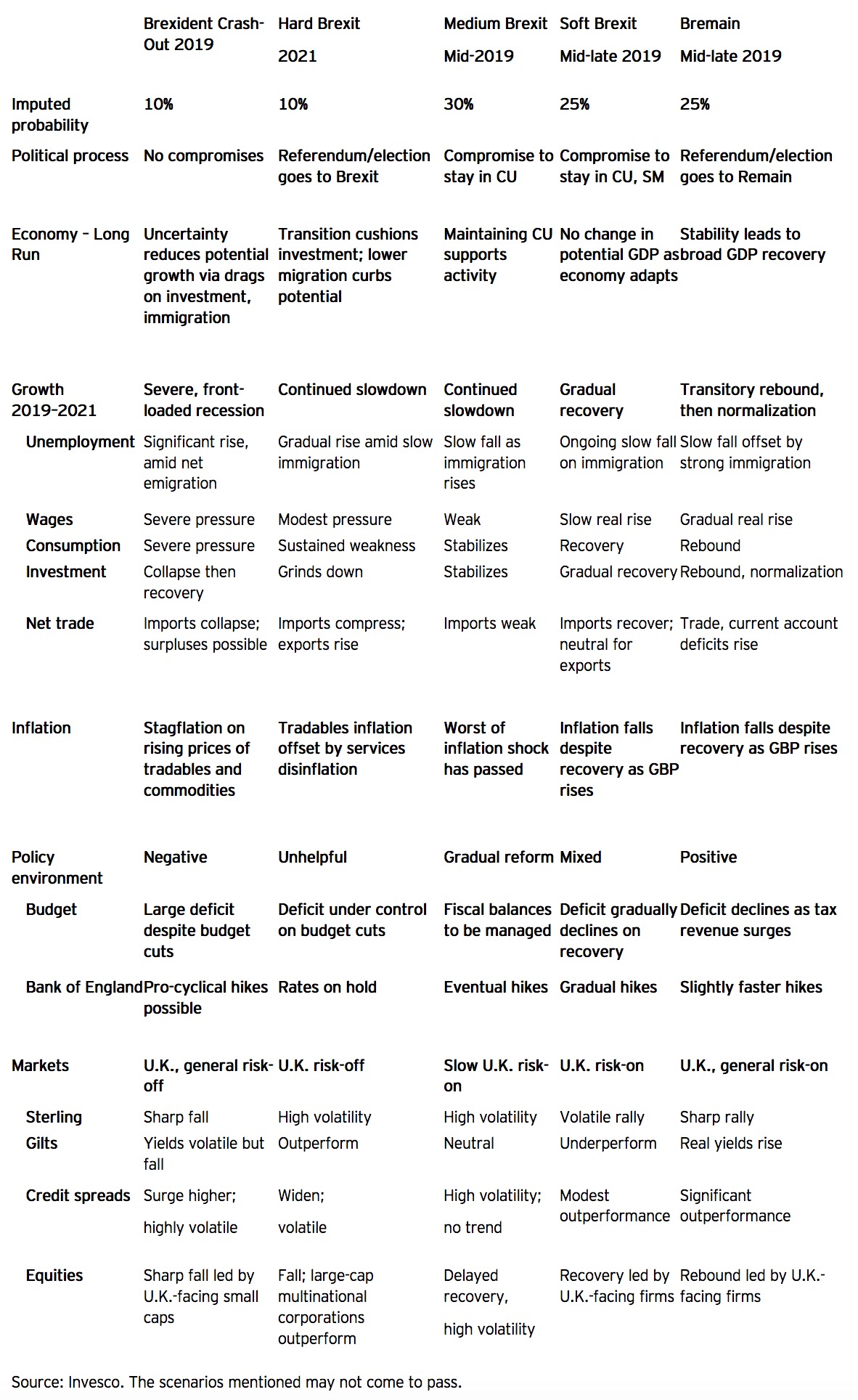

We would assign the following probabilities to each potential outcome.

- Brexident, 10% probability: If nothing is done, the U.K. will crash out of the EU with no transition. But the risk of a no-deal Brexit has fallen sharply as the U.K. Parliament has restricted the prime minister’s ability to manage a hard Brexit, and the ECJ has confirmed the U.K.’s right to revoke Article 50

- Hard Brexit, 10% probability: This would entail an exit from both the CU and the SM. The chances of a hard Brexit have significantly receded, in our view, as it has long been clear that there is only a minority, albeit a vocal one, for Brexit at any cost. But it is still conceivable that a new referendum or general election might lead to another majority for Brexit

- Medium Brexit, 30% probability: This would include an exit from the SM but membership in the CU, similar to the EU’s relationship with Turkey

- Soft Brexit, 25% probability: We could see a compromise by Parliament in which the U.K. remains in the CU and SM. While this would retain most of the U.K.-EU economic relationship, in line with the desires of most major firms and financials, it would be politically contentious within the U.K., given the Brexit referendum

- Bremain, 25% probability: This scenario, no Brexit at all, would likely require a new referendum or election. While their public positions indicate that a majority of MPs favour remaining, such a political choice would likely be portrayed as a betrayal of the will of the people, unless preceded by some sort of “people’s vote” endorsing a reversal of the 2016 referendum result. But a new plebiscite would be more complicated than before, given the need for several alternatives in line with these scenarios instead of the binary choice offered in the 2016 referendum, based on negotiations since then and increased awareness of EU rules.

Figure 1: The tangled web of potential Brexit scenarios and outcomes

The following chart represents our expectations for what each scenario could potentially mean for the economy, inflation, central-bank policy and

markets.

The bottom line of this tangled web of possibilities is three key investment implications:

- K. politics is still fertile ground for high economic uncertainty and market volatility

- We see a sizable 20% chance of an adverse outcome in the short term (either a Brexident or hard Brexit)

- And yet, we believe there is a relatively strong likelihood of more favourable outcomes for the U.K. economy in the near term with a decent outlook over longer horizons

What to look for beyond the (first) no-confidence vote

Brexit has been gearing up for two-and-a-half years since the June 2016 referendum, yet only now is it shifting into high gear as the clock runs down into the planned home stretch this quarter. The political strategies of both the Tories and Labour will be crucial during what should be the final stretch.

May’s game plan has in effect been to balance opposing forces and preferences within U.K. politics with EU rules. It has become clear with repeated capitulations that the EU has so far proven far more united and the United Kingdom anything but united on all key issues, especially the SM and CU.

We therefore expect an iterative process in which Parliament and parties rely on opinion polls – and possibly even a proper electoral poll – to solve for the least common denominator. This process is likely to involve considerable debate, probably with the acrimony and fireworks common in the U.K.’s famously no-holds-barred Parliamentary debates and tussles. Further votes on amended versions of the bill, with some likely defeats as well as subsequent and repeated no-confidence motions, are likely.

The scale of May’s defeat suggests that only a softer form of Brexit will be acceptable in Parliament – which we believe would point to an upside in sterling and U.K. equities, tighter sterling credit spreads and probably higher Gilt yields. But the real questions now are the following: How much softer can Brexit be and still fly without requiring a new referendum or election? How long will it take to get there? And what might be the collateral economic damage if the clock continues to run down toward a game of brinksmanship between hard-line Brexiters and Bremainers?

So far, May has been, if anything, defiant in Parliament – not conciliatory despite her unparalleled loss yesterday – which suggests that negotiation toward a compromise may well be fraught with ups and downs as she will try to keep hard-liners onside by pushing back against softening Brexit so much that it betrays the referendum. One metric of this approach – her plan to reach out to senior MPs (as opposed to party leadership) – suggests that she still plans to at least try to divide and conquer and bring MPs around to avoid really softening Brexit.

The underlying problem for both Tories and Labour is the political elevation of deep divides in U.K. society – young/urban/elite Bremainers versus older/more rural/more middle- or working-class Brexiters; and these are divides which cleave MPs, who prefer to remain or at most have a very soft Brexit, from much of the party rank and file who prefer exit. Indeed, we concur with the consensus view that MPs on average want a significantly softer form of Brexit than the May Withdrawal Bill; if anything, we would rank the average MP’s preferences as follows:

- Bremain (full membership): Although rejected in the referendum, this provided the U.K. with the closest partnership and most influence on EU policy, without having to adopt the euro

- Soft Brexit: Called Norway Plus because it adds the CU to Norway’s SM membership

- Medium Brexit: Continued permanent CU membership to maintain the integrity of the U.K. as well as the closest EU relationship that does not run afoul of the standard view of the referendum result

- Hard Brexit: Even if softened by a transition period and CU participation for as long as it takes to do an EU trade deal (essentially May’s deal, now dead in the water but which she may yet try to resurrect)

Conclusion

The centre of gravity is clearly a softer rather than a harder Brexit, but getting there may be fiendishly complex. What Brexit ultimately means may well hinge on balancing what qualifies as Brexit for the referendum majority against Parliamentary preferences for as soft a Brexit as possible. That in turn is likely to turn on May’s adherence to her “red lines” about free movement; Brexiters’ desires for the U.K. to be able to strike its own trade deals; and Labour leader Corbyn’s apparent desire to strike the right balance between Labour’s own internal splits on Brexit against those of the wider electorate and economy.

In short, Brexit is still up in the air.

Hence, our scenario analysis and imputed probability distribution still maintain a full spectrum of outcomes. We would expect the U.K. economy to remain weak, sterling volatile, Gilt yields suppressed and equities undervalued – until and unless the U.K. Parliament figures out how to opt for the softer Brexit it would prefer.

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog