Elga explains what our new estimates for the neutral rate reveal about the possible path forward for central banks.

The neutral rate is the level of interest rate at which monetary policy neither stimulates nor restricts economic growth. We have derived new estimates for this rate that reveal clues about the possible path forward for central banks.

Traditional estimates of the neutral rate can be limited, as we show in our latest Macro and market perspectives Navigating interest rates by the North Star. They do not take into account financial cycles–periods of rising and falling financial leverage–when estimating the neutral policy rate central banks should aim for to stabilize an economy at its trend growth rate. Rather they focus only on business cycles–periods of expansion and contraction in the economy – to derive a long-term neutral rate.

Yet over the past four decades the swings in financial cycles have increased materially. The past two U.S. recessions have been closely associated with major financial shocks, and financial super cycles can stretch well beyond the typical business cycle, such as in 2001 when the dot-com implosion and ensuing U.S. recession did not significantly disrupt credit flows. This suggests that financial super cycles, and the booms and busts they cause, need to be taken into account when looking at whether policy rates are stimulative or restrictive. It’s not enough just to incorporate business cycles, in our view.

Deriving our new neutral

We adapt earlier estimates of the neutral rate by incorporating financial cycles, using the so-called “credit gap” as a proxy. The credit gap measures the difference between total volume of private-sector inflation-adjusted credit and its long-term trend.

Based on this analysis, we arrived at two new neutral estimates: a long-term measure that would stabilize the economy if the financial cycle were also in a steady state, and a short-term rate that takes into account the current stage of the financial cycle. The short-term rate would need to be above the long-term rate, if debt ratios in the economy are growing. And the short-term rate would be below the long-term rate, if debt ratios are falling.

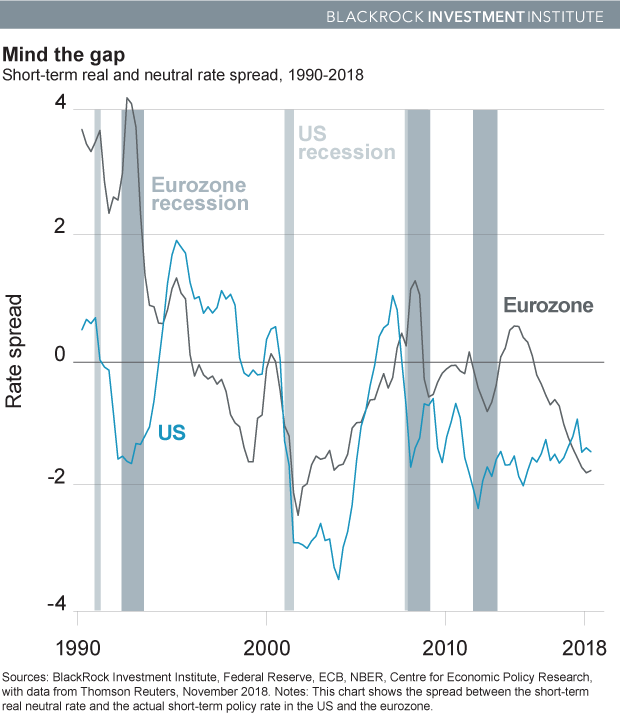

The short-term neutral rate can vary materially from the long-term trend, given that the length and magnitude of financial cycles have increased across developed markets since the 1980s. A sustained increase in financial leverage pushes our estimate of the short-term neutral rate above its long-term trend – as is happening in the U.S. now. A drawn-out phase of deleveraging, such as that after the financial crisis, pushes the neutral rate below its long-term trend – as is still the case in the eurozone.

What does this mean for monetary policy?

When economic output is above potential, policy rates should be kept above the neutral rate to hold down inflation. When we also take into account the financial cycle–specifically a sustained period of rising financial leverage–policy rates need to be even higher to prevent overheating. When the economy is deleveraging and animal spirits are subsiding, the central bank should cut rates even further below the long-term neutral level to prevent any deflationary drag from deepening.

Since the mid-1980s, the spread between real short-term policy rates in the U.S. and the short-term neutral rate has peaked at around 100 basis points (bps) in Federal Reserve tightening cycles and has bottomed out at around minus 200 bps in Fed easing cycles. It is currently at minus 150 bps. See the Mind the gap chart below. By this measure, the Fed still has some way to go to get to an interest rate that approaches neutral. And the broader message from our short-term neutral rate estimates is very clear: The Fed and European Central Bank (ECB) are both still providing policy stimulus.

Bottom line

Our neutral rate estimates, which incorporate the current U.S. financial upswing, argue for the Fed to lift rates above market expectations to prevent the real economy and the financial sector from overheating. A subdued financial cycle, by contrast, would keep our short-term estimate of neutral below its long-term trend. This suggests the ECB should keep monetary policy looser than the long-term trend to allow the credit cycle to recover. Read more in our latest Macro and market perspectives.

Elga Bartsch, Head of Economic and Markets Research for the BlackRock Investment Institute, is a regular contributor to The Blog.