by Jeffrey Kleintop, Chief Global Investment Strategist, Charles Schwab and Company

Key Points

- History shows us that when the unemployment rate and the inflation rate converged to become the same number a prolonged downturn for the economy and markets often followed.

- The threat of storms in the economy and markets seems to be moving from “Advisory” to “Watch,” as indicated by the narrowing gap between the unemployment rate and inflation rate in many of the world’s largest economies.

Recent market volatility has made some investors wonder if the economic cycle is ending and stocks are at the start of a prolonged decline. One indicator we are watching for signs of the potential for a recession and a deeper and prolonged decline in stocks is the gap between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. This indicator suggests that the risks are rising.

Mind the gap

Although it makes sense that a low unemployment rate suggests the economy may be near a peak, the unemployment rate that was low enough to mark the peak in the cycle was different each time. There has not been a single unemployment rate that has consistently signaled trouble ahead. Instead, it was the difference between the unemployment rate and the rate of inflation that has acted as a signal that the economy may be peaking. History shows us that when the unemployment rate and the inflation rate converge to become the same number, a prolonged downturn for the economy and markets often followed.

Why could this signal a peaking economy? After a recession as a new economic cycle is getting its start, unemployment tends to be high since a lot of people have lost their jobs and inflation tends to be low since business are forced to cut prices to attract customers. This results in a wide gap between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. But as the economy improves, more people find jobs and companies are able to raise prices, causing the gap to narrow. When the gap narrows to zero and the unemployment rate and the inflation rate are the same number, it has acted as a sign the economy was overheating and nearing a peak. About a year after the gap closed, recessions have often occurred and were accompanied by bear markets for stocks.

Gap by country

Let’s look at what this indicator is telling us about the prospects for some of the largest countries in the world: the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Germany and Australia.

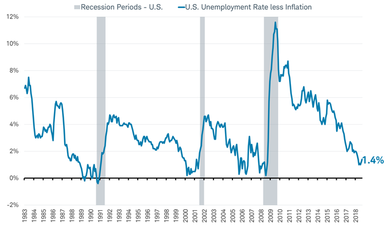

In the United States, the gap between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate (CPI) has closed ahead of each of the past three recessions in the U.S., as you can see in the chart below. At 1.4%, it is now getting close, but not there yet.

United States

Inflation measured by Consumer Price Index year-over-year % change.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/14/2018.

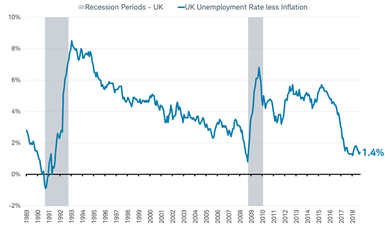

In the United Kingdom, the gap closed or narrowed to less than one percentage point ahead of recessions, as you can see in the chart below. At 1.4%, the same as the gap in the U.S., it is now also getting close.

United Kingdom

Inflation measured by Consumer Price Index year-over-year % change.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/14/2018.

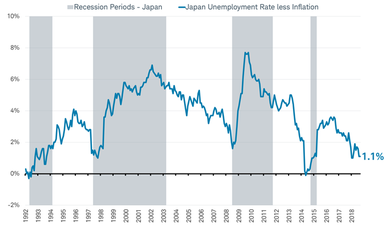

In Japan, the gap hasn’t always completely closed but did ahead of the latest recession in 2014, as you can see in the chart below. Currently at 1.1% it bears watching.

Japan

Inflation measured by Consumer Price Index year-over-year % change.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/14/2018.

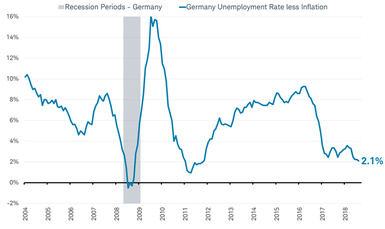

In Germany, we believe the gap between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate is best measured using the producer price index (PPI) rather than the consumer price index (CPI). Because Germany has the largest trade surplus of any country in the world, with nearly half of the country’s GDP coming from the production of exports, the PPI may be a better measure of prices. The reunification of Germany in the 1990s limits the comparable historical data we can look back to, but it is important to keep an eye on Europe’s largest economy. The gap in Germany has fallen to 2.1%, as you can see in the chart below.

Germany

Inflation measured by Producer Price Index year-over-year % change.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/14/2018.

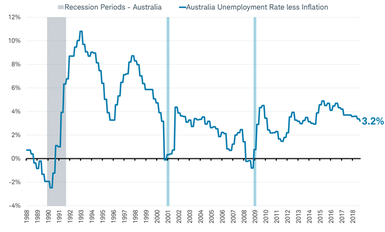

Australia has not technically had a recession since 1991, thanks in part to its proximity to China and its booming demand. However, Australia did have just one quarter in 2000 and 2008 where GDP fell by about one half of one percentage point. We shaded those a different color in the chart below to note they weren’t technically recessions, but were periods of weakness for the Australian economy and stock market that were signaled by the closing of the gap between the unemployment rate and inflation rate. At 3.2%, Australia is an outlier from the other countries we have presented, but it is worth noting how rapidly the gap closed from about 2-3% in prior periods.

Australia

Inflation measured by Consumer Price Index year-over-year % change.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/14/2018.

Recession watch

Summing up, the gap between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate is sending a similar message for many of the world’s largest countries: the gap hasn’t closed yet, but it may sometime in the next year or two. Adapting the severe weather storm scale definitions for the storms in the global economy and markets:

- Advisory = conditions for a recession may develop.

- Watch = conditions are favorable to a recession.

- Warning = recessions are occurring or imminent.

The threat of storms in the global economy and markets seem to be starting to move from “Advisory” to “Watch” as indicated by the narrowing gap between the unemployment rate and inflation rate in many of the world’s largest economies. This may mean stocks continue to see heightened volatility, even if a prolonged decline may not be the near-term forecast.