Four risks to watch in 2018

by Kristina Hooper, Global Market Strategist, Invesco Ltd., Invesco Canada

Our market outlook is positive, but institutional investors need to be ready for disruption

My base case for 2018 is that global growth will be solid and accelerating while global inflation will be low and benign. While I expect central banks around the world to tighten financial conditions, I believe the pace will be slow enough that overall financial conditions should remain accommodative. If my positive expectations for global growth, inflation and financial conditions come to pass, then the environment should be supportive of all risky assets in 2018, including credit and equity. However, we can’t ignore the potential risks to these conditions.

Risks to global growth

The global economy is experiencing accelerating growth. However, greater protectionism and growing debt levels could weigh on future growth prospects, if left unchecked.

- Protectionism

We are currently experiencing a trend of growing “economic nationalism” – also known as protectionism – which is threatening the future of key trade agreements and could result in the enactment of tariffs.

- The first sign of a U.S. shift on trade policy came soon after the Trump administration took office, as the U.S. withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – a trade agreement among 12 countries that border the Pacific Ocean and represent a substantial portion of the world’s economic output. The agreement was intended to reduce tariffs and break down barriers to free trade. While the withdrawal of the U.S. threw the status of the agreement into question, the other 11 nations have pledged to move forward, and the UK has signaled it would like to join TPP once it has left the European Union

- Now there is a growing likelihood that the U.S. could withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). If NAFTA is dissolved, I would expect to see only modest downward pressure on economic growth, although it could be more problematic for agriculture and the auto industry. If the agreement isn’t dissolved, it needs to be updated, given that it is nearly 25 years old

- Now the Trump Administration has begun levying tariffs, including significant ones on the steel and aluminum industries

It is important to note that protectionism usually does not occur in isolation, but can have a domino effect that results in a significant negative impact on global economic growth. Case in point: the Great Depression. The compounding effect of protectionist policies in the 1930s was documented by Barry Eichengreen and Douglas Irwin in The Journal of Economic History:

“The Great Depression of the 1930s was marked by a severe outbreak of protectionist trade policies. Governments around the world imposed tariffs, import quotas, and exchange controls to restrict spending on foreign goods. These trade barriers contributed to a sharp contraction in world trade in the early 1930s beyond the economic collapse itself, and to a lackluster rebound in trade later in the decade, despite the worldwide economic recovery.”1

Acts of protectionism usually result in retaliatory acts of protectionism, such as additional tariffs. We could also see retaliation in the form of a drop in foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, Canadian investment comprised 10% of the total FDI in 2016. However, according to the Bank of Canada’s January 2018 Monetary Policy Report, “Trade-policy uncertainty is expected to reduce the level of investment by about 2% by the end of 2019.”

- Rising debt levels

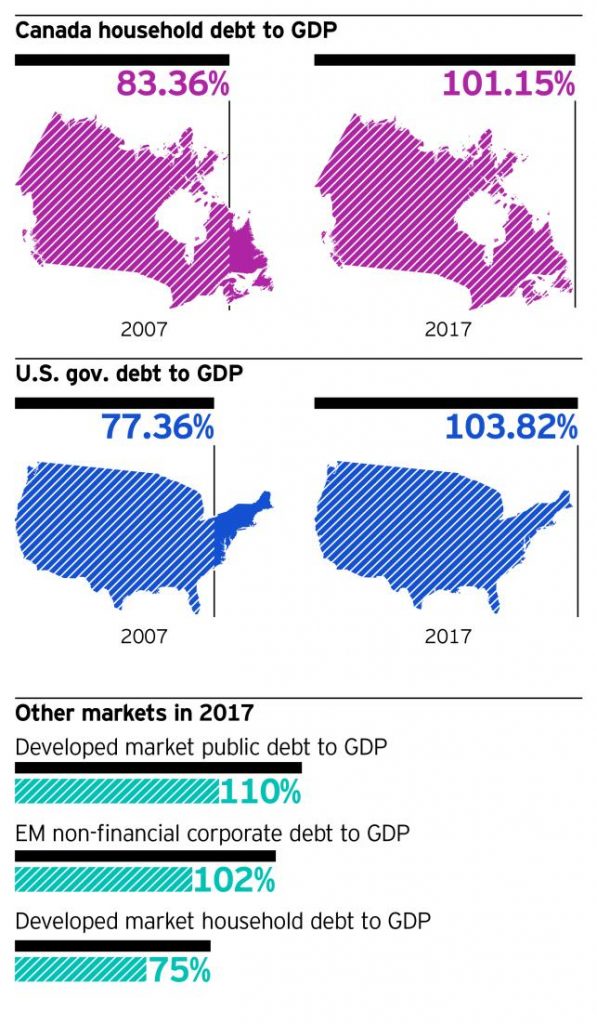

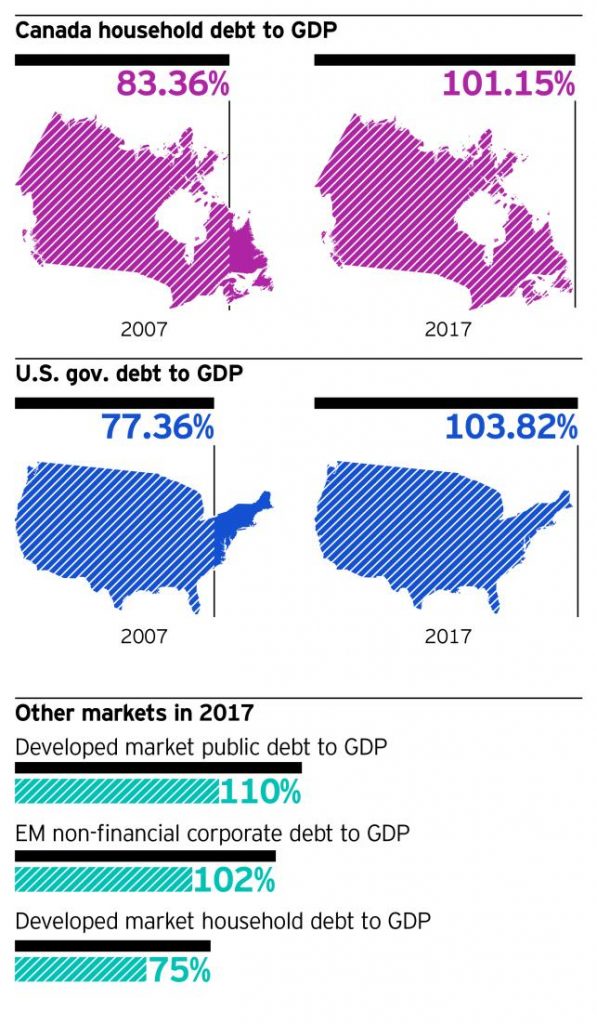

Contrary to conventional wisdom, there has not been a deleveraging in the past decade. Rather, we are seeing increasing debt levels – both public and private – in a variety of regions, and debt is expected to keep growing. The following are just a few examples:

- Canadian household debt has risen past the very high levels that U.S. household debt reached in 2007, raising the specter of a similar crisis in the future2

- U.S. household debt rose to a new record of $13 trillion in the third quarter of 20173

- U.S. government debt is currently at $15 trillion and is projected to grow to $26 trillion by 20274

The Japanese gross government debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 240% in 2017, which the IMF believes will rise based on current policies5

Source: Canada household to GDP – Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis as of September 30, 2017 Other markets in 2017 – Bank of International Settlements as of October 31, 2017

As research by U.S. economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff has shown, countries with higher debt-to-GDP ratios typically experience lower levels of GDP growth. This makes sense, given that the interest payments on that debt could be put to better use on activities with higher returns on investment, such as education or infrastructure. The same argument can be made for companies and households, both of which could benefit from investing their money rather than using it to service debt. Recent research has shown that a 1 percentage point increase in the household debt-to-GDP ratio is associated with growth that is 0.1 percentage point lower in the long run.6 For example, high levels of student debt in the U.S. have delayed household formation and prevented many young people from purchasing homes.

Debt can become particularly burdensome in a rising rate environment. In fact, I worry that we are nearing a debt crunch as monetary policy begins to tighten and interest rates begin to rise globally. Both public and private debt will become more difficult to manage in this environment, taking away resources from more productive uses. Corporate debt levels may prove problematic for highly leveraged companies, particularly for those in the U.S. given that the new U.S. tax reform legislation discourages the use of debt financing. And household debt levels are rising in many countries, suggesting a small margin of error if a new crisis arises.

Risks are exacerbated when debt is unsecured or the debtor is a poor credit risk. Consider:

- There has been a proliferation of subprime auto loan issuance in the U.S., which now comprises 24% of all outstanding auto loans.7 And the delinquency rate on those subprime auto loans is on the rise. In particular, subprime auto loans originated by auto finance companies (which originate the vast majority of these loans) experienced a delinquency rate of 9.7% in the third quarter of 2017 – the highest level since the first quarter of 2010 when households were still recovering from the global financial crisis.8

- Loans to riskier entities in China have grown in recent years. For example, private-sector enterprises experienced a profit increase of 18% between 2011 and 2016, while state-owned enterprises (SOEs) experienced a profit decrease of 33% for that same time period.9 However, SOEs’ share of corporate liability growth rose from 59% in 2010 to 80% by 2016 while, of course, private-sector enterprises saw their share of overall corporate debt fall.10 This is both surprising and concerning.

Risks to financial markets

Most asset classes are fairly valued or overvalued after significant price increases in the past several years. In particular, valuations are stretched for U.S. stocks and are even frothier for U.S. Treasuries, which make these asset classes especially vulnerable to potential risk scenarios. Key market risks in this environment include tighter-than-expected monetary policy and the possibility of lower profit margins.

- Tighter-than-expected monetary policy

I have argued for more than a year that normalization of monetary policy presents a risk to financial assets. We have to remember that the large-scale asset purchases that have been a key policy tool of some major central banks over the past decade are experiments that have had a very significant impact on asset prices and market volatility. Now that central banks are starting to “normalize” this experimental monetary policy, there is the potential for disruption to capital markets. While this is not my base case, this is a distinct possibility, especially given that this potential is amplified by several different factors that all increase the odds of a policy error:

- First, in the U.S., there will be a significant number of new Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voting members in 2018, and there is also a new chair – the first non-economist to hold that post in decades.

- Second, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) is utilizing two different monetary policy levers simultaneously – the federal funds rate and the Fed’s balance sheet.

- Finally, several other major central banks are starting to normalize monetary policy as well, albeit ever so gently.

The risk that tightening may occur too quickly in the U.S. is exacerbated by the 2017 tax reform legislation. There is legitimate concern that implementing tax cuts at a time when the global economy is accelerating could cause the economy to overheat. In fact, the FOMC contemplated this possibility in December, as was indicated in the group’s meeting minutes. In turn, concerns about higher inflation could cause the Fed and other central banks to pre-emptively tighten monetary policy, or tighten too quickly. Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley recently warned about this possibility, suggesting that the Fed may have to “press harder on the brakes” in the next several years if the economy accelerates, which increases the possibility of a hard landing for the economy. We could see a sudden adjustment in asset prices as well as yields, spreads and risk premiums. This could be a significant disruption that creates higher volatility, particularly to the downside.

- Narrowing profit margins

While this is not my base case, there is also the risk that earnings may come under pressure if inflation, particularly wage growth, rises. We are already seeing some upward pressures on wage growth in the U.S., as reported in the January 2018 Federal Reserve Beige Book. The January 2018 employment situation report revealed that average hourly earnings rose 2.9% for the year, a level that had not been seen in years and suggested wage growth is rising significantly. In fact, the minimum wage has been raised in a number of municipalities in the U.S., which should put upward pressure on wage growth. Fortune magazine reported in December that 2018 will bring minimum wage increases for workers in 18 U.S. states and 20 American cities.

Wage growth could rise in other parts of the world as well as pressure points develop:

- South Korea’s minimum wage will rise by 16.4% to 7,530 won (U.S.$6.65) an hour this year – the biggest wage hike since 2000.11 The target minimum wage by 2020 is 10,000 won, which constitutes an increase of 55% in total.12 This would elevate South Korea’s minimum wage to approximately 70% of its median wage – a much higher level than in other major economies.13

- In December, Japan enacted new corporate tax cuts that are tied to incentives such as wage growth; specifically, corporate taxes will fall to 25% for those companies that raise wages by 3%.14

- A number of provinces in Canada are also experiencing minimum wage increases. While most will be modest, Ontario’s minimum wage will rise more than 20% this year, which represents the largest minimum increase in more than 40 years, and Alberta’s minimum wage is planned to increase more than 10%.15

Summary

In short, there are a number of growing risks that could potentially lead to a global growth slowdown, lower corporate revenues and pressure on profits. We have to keep in mind that expensive asset classes are particularly vulnerable and need to be supported by fundamentals. In either a higher wage growth or a lower revenue growth scenario, weakness in earnings could cause a re-rating of these asset classes. And of course there is a particular risk of equities re-rating as rates rise. Finally, as we assess risk scenarios, we can’t ignore the interconnectedness of asset classes and regions, increasing the possibility of contagion if one area experiences turbulence.

Therefore, we need to be cognizant of the risks to what is a positive base case scenario for 2018. This includes a sensitivity to valuations and attention to hedging the risks of rising inflation through inflation-hedged securities, commodities such as gold, and real estate. This also includes an emphasis on broad diversification and downside mitigation, including alternative asset classes that have low or negative correlation16 to stocks. 2018 is likely to be a very different market environment than 2017.

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog