by Jurrien Timmer, Director of Global Macro, Fidelity Global, Fidelity Investments Canada, @TimmerFidelity

FEBRUARY 2018

Two Roads the Market May Follow

Glimpsing the potential direction of stocks from the market’s current secular trend.

Key Takeaways

• A historical analysis of prior secular bull markets suggests that the current bull market could continue in the years to come.

• One counterargument against this rosy secular outlook is that, over the long term (at least 10 years), high starting valuations tend to lead to lower future returns.

• That said, there are plenty of times when the market’s price action is a function of more than just starting valuations.

• Despite the mixed signals, both scenarios imply that the bull market could continue into 2019.

Looking beyond 2018 and 2019, there are two diverging paths the stock market could potentially follow. One is a continuation of the current secular bull market; the other is a valuation-driven decline in market growth.

Secular Super-Cycles

Five years ago I wrote a report “Are We at the End of the Secular Bear Market for Stocks?” At the time the evidence was still inconclusive, but I was hopeful that the bear market had indeed ended. Now, with five more years of history under our belt and following the market’s epic run in 2017, it is worth revisiting this question.

To recap, secular trends are “super-cycles” or very long trends in which the stock market generates a return stream that is either well above-trend (secular bulls) or well below-trend (secular bears). The secular trend is like a pendulum that oscillates around the stock market’s “central trend” (the market’s historical average annual growth rate), either by moving away from it or toward it.

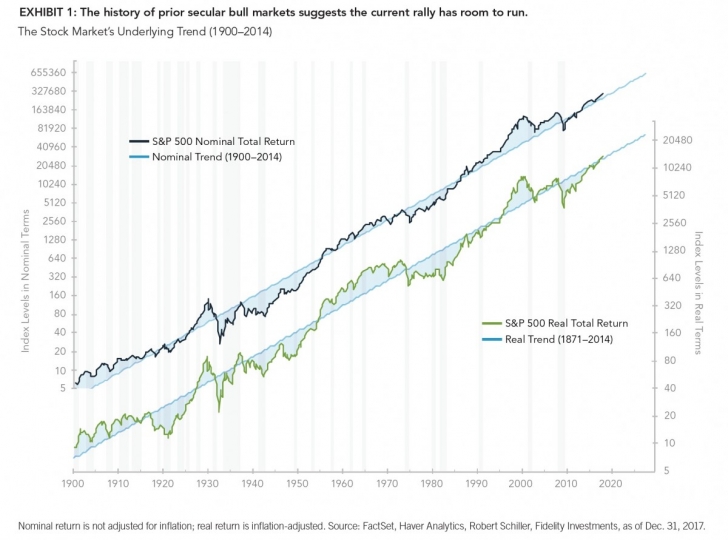

From 1928 through 2017, the central trend for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P 500) was roughly 10% in nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) terms and 7% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.1 These secular trends tend to persist for one to two decades and span multiple shorter market cycles. For instance, the 1949–1968 and 1982–2000 periods were secular bull markets, whereas the 1929–1948 and 1968–1982 periods were secular bear markets.

When I wrote the report five years ago the question was relevant because investors had just suffered through more than a decade of sideways-to-down returns (including two 50%-plus declines), and finally the stock market was approaching its old highs again of around 1,550 for the S&P 500. The 2000s was a secular bear market that included first the dot-com bubble and later the global financial crisis. It left many investors traumatized and underinvested

Nominal return is not adjusted for inflation; real return is inflation-adjusted. Source: FactSet, Haver Analytics, Robert Schiller, Fidelity Investments, as of Dec. 31, 2017. in equities, and seeking shelter in cash and bonds. So, asking the question of whether that secular bear was transitioning to a secular bull was important from an asset allocation perspective, considering that the prospect of outsized returns was on very few people’s radar.

The Secular Bull Market Road Map

The history of secular trends may help to figure out the market’s current regime. When looking at the market’s central trend and the secular trends that oscillate around it, it prompts two questions: First, how far and for how long does the secular pendulum swing away or toward that rising trend-line before a super-cycle is complete; and second, how does that compare to the post-2009 trend? The answer is that the S&P 500 tends to fall about 50% below its trend line at secular lows, and rises to about 100% above trend at secular peaks. From bottom to top this period tends to last 18 years; from top to bottom it tends to last about 13 years.

How does this compare to today’s market? Let’s look at Exhibit 1 (see page 2). As shown in the chart at the March 2009 low, the S&P 500 was 47% below its central trend line in real terms, and today it is 14% above its trend line. That’s a 61 percentage point roundtrip in real terms. This is very consistent with past secular bulls, especially the ones that started in 1949 and 1982. If we simply compare where the S&P 500 is currently trading just nine years after the 2009 low to where it was at that same point following the start of these two previous two secular bull markets (1949–1968 and 1982–2000), we find that the analog is almost perfect. That suggests that, at least superficially, the market’s outsized 18% annual gains since the 2009 low may well continue for years to come.

One statistical shortcoming of looking at secular trends is that, by definition, there haven’t been many of them. After all, if we have an observable (i.e., chartable) market history of 100–150 years, and each secular trend spans 14–18 years, then there will only be so many observations on which to base our analysis. That’s not statistically robust. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t look at market history and price analogs in an attempt to learn from the past. Market behavior is a subset of human behavior after all, and history does tend to rhyme.

Valuation Road Map

One counterargument against the rosy secular bull analog is firmly rooted in market history. Over the long term (at least 10 years), high starting valuations—as measured by price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios—tend to lead to lower future returns; conversely, low starting valuations often lead to above-average returns. Valuations have little bearing on future returns in the short to medium term.

In a way this pattern makes sense, because the market’s P/E tends to mean-revert around a central value of around 15x. Again, it’s like that pendulum, only this time it’s a level instead of a growth rate. Therefore, if someone begins investing when the market’s P/E is at 30x instead of 15x, there will likely be a “valuation payback” over the long term, as the investor is ultimately penalized for this high starting valuation.

Looking at the market’s total return of the past 10 years shows that it has had a high correlation to the market’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio from 10 years ago. Let me repeat: Historically, the market’s current return profile may be explained by its valuation a decade earlier. For the valuation I’m using the S&P 500’s 10-year cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE), and for the return I am using its 10-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

Let’s call this the CAPE model.

Ten years ago in late 2007, the 10-year cyclically adjusted P/E was 29x, which at the time projected that today’s 10. year CAGR would be 8%. The actual 10-year CAGR as of November 2017 was 8.2%.2 Of course, it doesn’t always work this well (nothing does), and there are at least two limitations with the CAPE model. First, no matter how accurate, a 10-year CAGR isn’t going to tell us what will happen over the next year or two. So this model has its limits for active allocation and may be more useful for strategic allocation purposes.

Second, and more importantly, this model’s only explanatory factor is its starting valuation, and there are plenty of times when the market’s price action is a function of more than where valuations were a decade earlier. For instance, the dot-com bubble was not predicted by the CAPE model, because 10 years earlier (in 1990) the market wasn’t cheap enough (at 20x) to warrant such high returns in 2000. Plus, it was a bubble, which by its very definition means valuations were neither justified nor predictable by any fundamental measure. Similarly, the CAPE model did not predict the low returns of the 1970s, because valuations were not high enough during the 1960s to produce such an outcome. The CAPE was indeed high during the 1960s (25x at the 1968 secular top) and, therefore, directionally correct in predicting the weak returns a decade later, but it was not high enough to capture the magnitude of the very poor returns of the 1970s.

So, the CAPE model should be merely one of many inputs to consider when investing, especially for anyone who is not anchored to a single starting point (which would be the case for anyone who is dollar-cost-averaging). Nevertheless, I think this is a good model to keep handy for strategic asset allocation purposes, and conceptually I think the idea makes sense, in that an expensive starting point acts as a headwind for future returns, while a cheap starting point creates a tailwind. I bring up this model because it’s been predicting that the current 10-year CAGR of 8% will accelerate to 18% by early 2019, but then will start to decline before ending at around 4% in 2028. That’s not consistent with the secular bull market road map I described earlier, which suggests the market will just keep going higher. The reason for the acceleration and subsequent drop-off is the fact that by early 2009 the CAPE had fallen to 11x, predicting an outsized CAGR over the subsequent 10 years. And now, in 2017, the CAPE is 30x, predicting sub- par returns over the coming 10 years.

Reconciling the Two Road Maps

The way I reconcile the different potential outcomes beyond 2018–2019 is by recognizing that valuations are much higher today than they were at this point in the previous two secular bull markets. Nine years into the 1949–1968 secular bull market the CAPE was at 15x, and nine years into the 1982–2000 bull it was at 20x. Today’s valuation is much higher at 30x; therefore, there may be more of a payback down the road.

Why is the CAPE so high? I think it has to do with monetary policy and the resulting suppression of risk premium. In my view, the unconventional global easing cycle since 2008 is in large part responsible for the collapse in the term premium3 in the bond market, which in turn has inflated the valuation of everything (given the role that the risk-free rate plays in valuing assets). This makes the CAPE model and its negative implications past 2018 a particularly relevant one to keep in mind in the coming years as the global easing cycle goes in reverse, possibly taking with it the bond market’s low term premium and elevated valuations.

For this reason, my guess is that the CAPE model will beat out the secular price analogs once we get past 2018 or 2019. But for now the two road maps agree that the bull market could continue into 2019. That’s consistent with the robust earnings picture and the fact that the Federal Reserve Board has not raised interest rates nearly enough to derail the business cycle.

Author

Jurrien Timmer | Director of Global Macro, Fidelity Global

Asset Allocation Division Jurrien Timmer is the director of Global Macro for the Global Asset Allocation Division of Fidelity Investments, specializing in global macro strategy and tactical asset allocation. He joined Fidelity in 1995 as a technical research analyst.

For Canadian investors

For Canadian prospects and/or Canadian institutional investors only. Offered in each province of Canada by Fidelity Investments Canada ULC in accordance with applicable securities laws. 1. Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., as of Dec. 31, 2017.

2. Source: Haver Analytics, Robert Shiller, Fidelity Investments, as of Nov. 30, 2017.

3. An asset’s risk premium is a form of compensation for investors who tolerate the extra risk—compared to that of a risk-free asset—in a given investment.

Unless otherwise disclosed to you, any investment or management recommendation in this document is not meant to be impartial investment advice or advice in a fiduciary capacity, is intended to be educational, and is not tailored to the investment needs of any specific individual. Fidelity and its representatives have a financial interest in any investment alternatives or transactions described in this document. Fidelity receives compensation from Fidelity funds and products, certain third-party funds and products, and certain investment services. The compensation that is received, either directly or indirectly, by Fidelity may vary based on such funds, products, and services, which can create a conflict of interest for Fidelity and its representatives. Fiduciaries are solely responsible for exercising independent judgment in evaluating any transaction(s) and are assumed to be capable of evaluating investment risks independently, both in general and with regard to particular transactions and investment strategies.

Information presented herein is for discussion and illustrative purposes only and is not a recommendation or an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities.

Views expressed are as of the date indicated, based on the information available at that time, and may change based on market and other conditions. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions provided are those of the author and not necessarily those of Fidelity Investments or its affiliates. Fidelity does not assume any duty to update any of the information.

Investment decisions should be based on an individual’s own goals, time horizon, and tolerance for risk.

Nothing in this content should be considered to be legal or tax advice, and you are encouraged to consult your own lawyer, accountant, or other advisor before making any financial decision.

Stock markets, especially non-U.S. markets, are volatile and can decline significantly in response to adverse issuer, political, regulatory, market, or economic developments. Foreign securities are subject to interest rate, currency exchange rate, economic, and political risks, all of which are magnified in emerging markets.

Investing involves risk, including risk of loss. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Diversification and asset allocation do not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss.

All indices are unmanaged. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Index definitions

Standard & Poor’s 500 (S&P 500®) Index is a market capitalization–weighted index of 500 common stocks chosen for market size, liquidity, and industry group representation to represent U.S. equity performance. S&P 500 is a registered service mark of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., and has been licensed for use by Fidelity Distributors Corporation and its affiliates. Third-party marks are the property of their respective owners; all other marks are the property of Fidelity Investments Canada ULC.

Cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) is a valuation measure usually applied to the U.S. S&P 500 stock market. It is defined as price divided by the average of 10 years of earnings, adjusted for inflation.

Compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is the mean annual growth rate of an investment over a specified period of time longer than one year.

© 2018 Fidelity Investments Canada ULC. All rights reserved. CAN: 832511.1.0 U.S.: 831022.1.0