by Jean Boivin, PhD, Head of Economic and Markets Research at the BlackRock Investment Institute

Reflation means different things to different people. Jean explains some of the reasons why reflation (as BlackRock defines it) has room to run.

The phrase “reflation trade” gets bandied about even though it is poorly defined, meaning different things to different people. Right now, “reflation” is being used to refer to everything from inflation to economic expansion to U.S. President Donald Trump’s tax and deregulation plans.

We believe the economic reflation story needs to be separated from the many “trades” tied to it, as my colleagues and I write in our new Global Macro Outlook Benchmarking Reflation.

Rapid market repricing on a brighter growth and inflation outlook unfolded over just a few months in late 2016, largely because investors were quickly reassessing their views after having been overly downbeat about growth prospects due to the energy and commodity price shock. China’s pick-up, thanks to heavy stimulus, also played a role in helping emerging markets bounce back. We believe that reassessment is largely over. However, this doesn’t mean economic reflation is over too. We believe the global reflation dynamic has more room to play out.

We see U.S. growth holding at a slightly above-trend pace that should keep intact reflation as we define it: rising wages feeding stronger nominal growth, allowing lingering slack from the last recession to be gradually eliminated in a way that stirs broader inflation pressures.

We see two factors as being supportive of economic growth: Households are in much better shape to sustain spending after a historic deleveraging following the 2007-08 financial crisis, and corporate investment should reinforce growth rates. We see some risks that the current political drama in Washington D.C. could keep businesses cautious. But at this point in the economic cycle, corporate investment has been unusually weak—both in the U.S. and Europe. A change could be ahead.

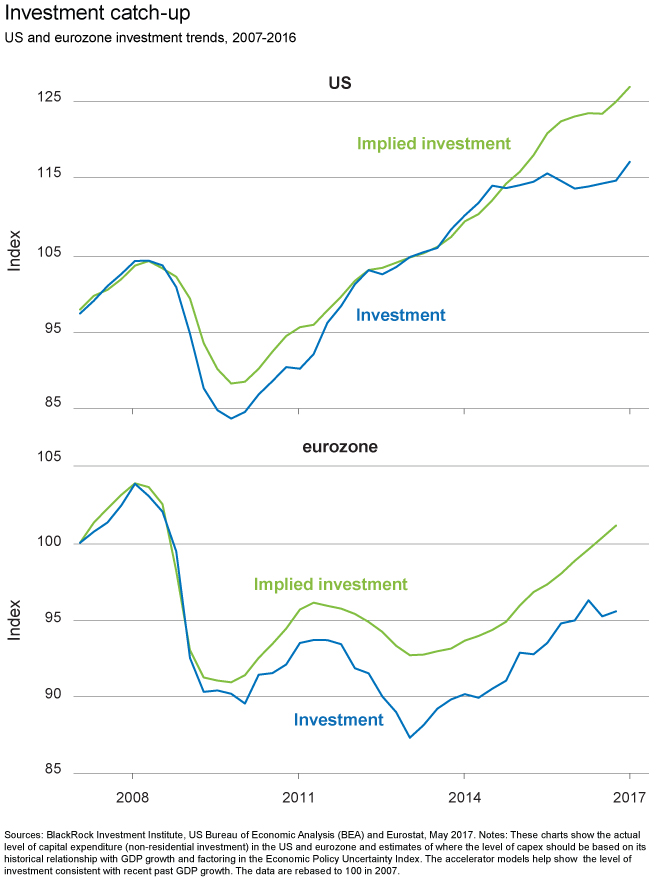

U.S. capex overshot to the downside in the wake of the 2008–09 financial crisis, deviating from its past relationship with gross domestic product (GDP) growth. The upper chart below shows the level of non-residential investment—from computers to buildings, government projects, and intangibles such as research and development—implied by U.S. and eurozone GDP.

In the U.S. case, investment eventually caught up to a level consistent with the modest growth environment and higher corporate uncertainty. Then the energy shock struck. Central banks were feared to be out of ammunition, heightening worries about deflation. The investment gap reopened. This underscores how corporate investment has been something of a missing ingredient over the past few years, softer than it should be even when we account for lower potential growth. In Europe, the investment gap is very far from being closed. See the lower chart above. Greater investment in Europe could reinforce its sturdy recovery.

In general, our analysis shows that these investment gaps tend to be corrected. This would happen as companies gain enough confidence to unleash spending once economic conditions stabilize—and the proverbial “animal spirits” kick in. Corporate guidance in earnings updates suggests a reluctance to spend. Yet the Philadelphia Federal Reserve’s survey of manufacturer investment intentions shot up to a 17-year high in April. U.S. first-quarter business investment growth was its strongest since 2013, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Bottom line: Stronger corporate investment would reinforce growth rates, just one of the reasons we believe reflation has legs. Read more economic insights in our latest Global Macro Outlook.

Jean Boivin, PhD, is head of economic and markets research at the BlackRock Investment Institute. He is a regular contributor to The Blog.

Copyright © BlackRock