by Benjamin Streed, CFA, Raymond James

The past week brought with it the first concrete signal that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), more commonly known as “the Fed”, would likely begin to taper the size of its massive ~$4.5 trillion balance sheet sometime in the future. The details of the Fed’s March meeting, in which they hiked rates by 25 basis points with only one dissenting vote, included a basic roadmap for how this will likely materialize.

A reduction of both Treasury and mortgage securities was always understood to be an inevitability, but the real question revolved around when it would begin (likely later this year), how quickly it would commence and how the central bank would communicate with the markets as it heads into uncharted waters yet again. At this juncture, the summary appears to be the following: they will allow bonds to “roll off” and it will be done gradually over a long period of time. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President John Williams said it may take five years to shrink the balance sheet to a more normal size (not entirely eliminate it). Williams also said officials would likely move slower on future rate increases and the reduction of the balance sheet if both measures are utilized together.

Interestingly enough, some Fed officials have even made remarks that the normalization/reduction of their holdings could be implemented instead of another hike in the federal funds rate, thereby replacing their primary monetary policy tool with an entirely new one. As a result of this announcement, bonds rallied on Wednesday signaling that markets were anticipating some sort of communication on this topic and the idea of a “taper instead of a hike” change in language was initially seen as somewhat dovish.

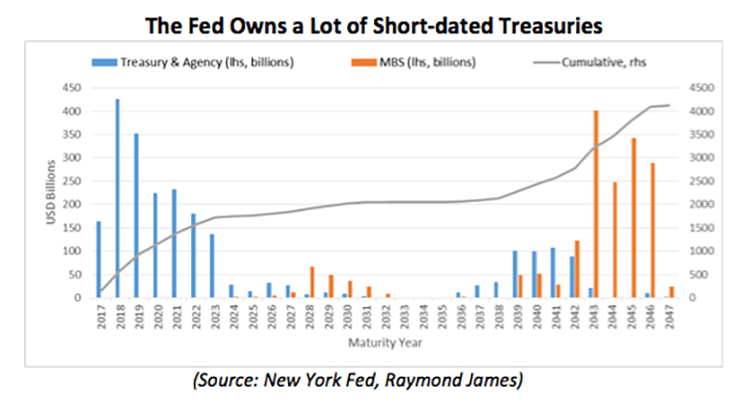

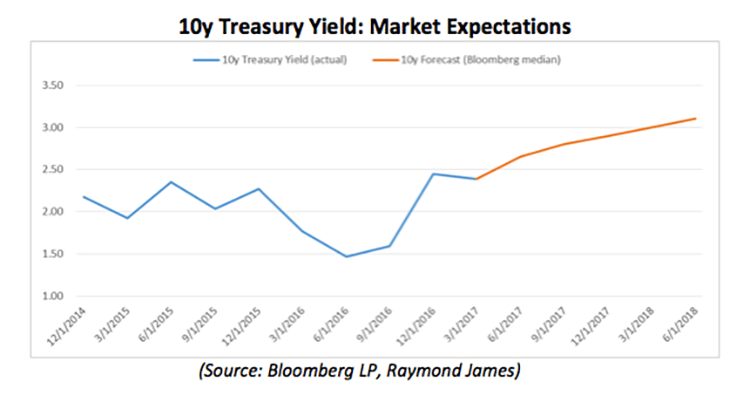

The chart above details the state of the Fed’s balance sheet as of the end of March, and worth a reminder that a significant portion of their overall holdings are short-term Treasuries due in less than five years. For example, should the Fed undertake a “roll off” approach, by 2022 a cumulative $1.5 trillion of securities would vanish representing roughly one third of the total. Despite this additional color on the Fed’s plan, market expectations for the yield on the 10-year Treasury haven’t moved meaningfully. The chart below details the median expected yield (orange) of 55 economists surveyed by Bloomberg. Interestingly, the yield curve flattened on the announcement and bonds saw further strength after the weak payrolls report on Friday morning.

So where does this leave the markets? On one hand, we saw the 10-year Treasury yield fall below 2.30% for the first time in 2017 due to the Syrian airstrike which pushed us to 2.29%. The payrolls report saw further declines in yields to roughly 2.27%, yet both times markets resisted a move much lower, potentially establishing a resistance level in the 2.30% area. Markets are pricing in a strong possibility of yet another Fed rate hike in June (yet very little chance in May). June odds now sit at 66% according to Bloomberg data, and we could find ourselves in the 2.30-2.40% trading range unless something comes along to upset the applecart. Market expectations for increasing yields have been something of a “broken record” in the post-recession world and 2017 is once again showing that there is a very real struggle between expectations and reality.

Copyright © Raymond James