by Corey Hoffstein, Newfound Research

This blog post is available for download as a PDF here.

- Modern portfolio theory provides a way for investors to identify the efficient frontier: the set of portfolios that maximize return per unit of risk.

- Taken to its logical conclusion, modern portfolio theory states that all investors should invest in the same global market portfolio and increase or decrease risk through the use of leverage or cash, respectively.

- In practice, investors appear to exhibit aversion to both leverage and cash. While leverage introduces operational hurdles, the aversion to cash appears to be merely behavioral.

- Overcoming these behavioral biases may be prudent as we may be doing a disservice to conservative investors by not utilizing a blend of a riskier portfolio and cash.

- We find that given today’s market outlook (using J.P. Morgan’s 2017 capital market assumptions), increasing the cash allocation does not meaningfully change results for conservative investors as the Sharpe optimal portfolio is highly conservative already.

In his 1952 article “Portfolio Selection,” Harry Markowitz outlined the foundations of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). The biggest breakthrough of MPT was that it provided a mathematical formulation for diversification.

While the concept of diversification has existed since pre-Biblical eras, it had never before been quantified. With MPT, practitioners could now derive portfolios that optimally balanced risk and reward. For example, by combining risky assets together, Markowitz created the efficient frontier: those portfolio combinations for which there is the lowest risk for a given level of expected return.

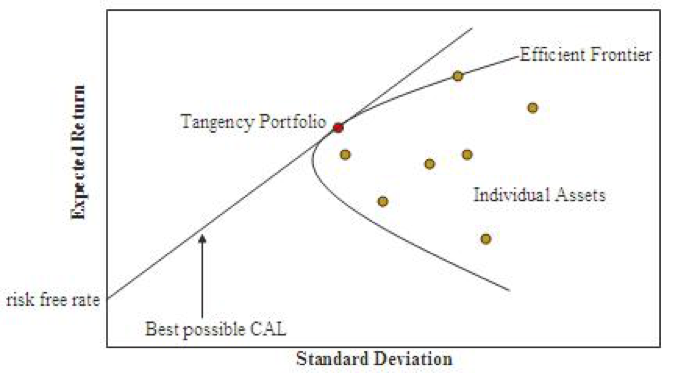

By introducing a risk-free asset, the expected return of any portfolio constructed can be linearly changed by varying the allocation to this risk-free asset. In a graph like the one below, this can be visualized by constructing a line that passes through the risk-free asset and the risky portfolio (called a Capital Allocation Line or CAL). The CAL that is tangent to the efficient frontier is called the capital market line (CML). The point of tangency along the efficient frontier is the portfolio with the highest Sharpe ratio (excess expected return divided by volatility).

Image Source: Wikipedia

According to MPT, in which all investors seek to maximize their Sharpe ratio, an investor should only hold a mixture of the Sharpe optimal portfolio and the risk-free asset. Increasing the allocation to the risk-free asset decreases risk while introducing leverage increases risk.

Note: In this commentary, while we will refer to the risk-free asset as “cash,” we really mean U.S. Treasury Bills – or T-Bills – which are U.S. government bonds issued in 3-, 6-, and 12-month maturities. In brokerage accounts, cash is often swept into a money market fund, which usually hold a high percentage of T-Bills.

The fact that any investor should only hold one portfolio has a very important implication: given all the assets available in the market, all investors should hold, in equal relative proportion, the same portfolio of global asset classes.

Holding anything but a combination of the tangency portfolio and the risk-free asset is considered sub-optimal.

In practice this means that if a portfolio like the “60/40” is Sharpe optimal, then conservative investors should hold a blend between the 60/40 and cash, while more aggressive investors should apply leverage.

Yet rarely have we ever come across an investor who actually invests in this manner. Instead we see two common behaviors:

- An aversion to the use of leverage. In practice, instead of using leverage, investors appear to prefer increasing portfolio volatility through the use of higher volatility assets. In fact, this preference is posited as being one of the primary reasons for the existence of the low volatility anomaly.

- An aversion to the use of cash. In our experience, financial advisors feel pressure to maintain a full investment profile for their clients, with cash being viewed as undeployed capital rather than as a risk ballast.

While the introduction of leverage also comes with operational hurdles, an aversion to the use of cash appears to be merely a behavioral issue.

If the only thing preventing us from doing this is a behavioral bias against cash, are we doing ourselves a disservice by not trying to overcome it?

Is Cash Worth It Today?

To test the opportunity cost of ignoring cash in today’s environment, we will utilize J.P. Morgan’s recently released 2017 capital market assumptions to create mean-variance optimal portfolios.

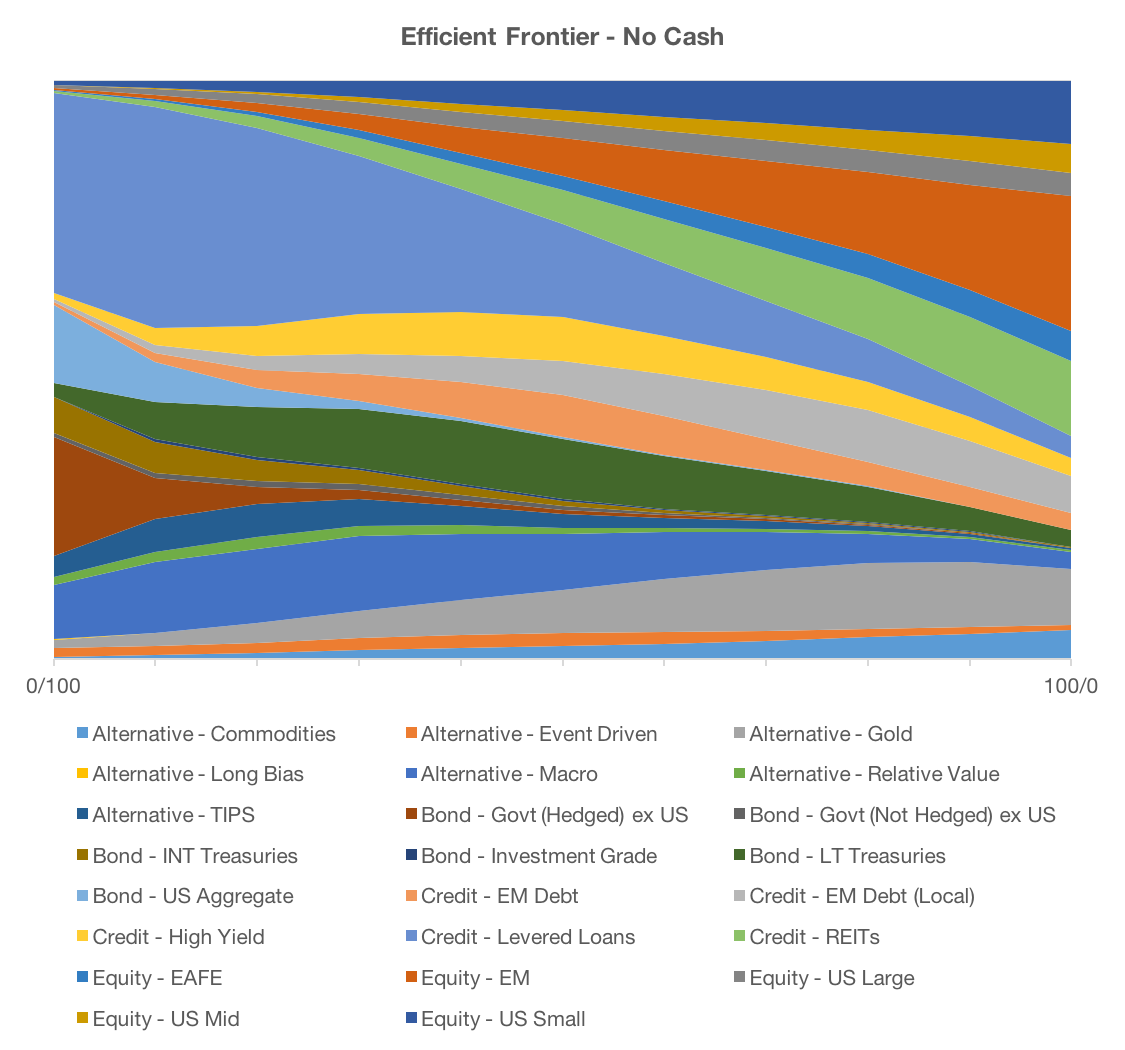

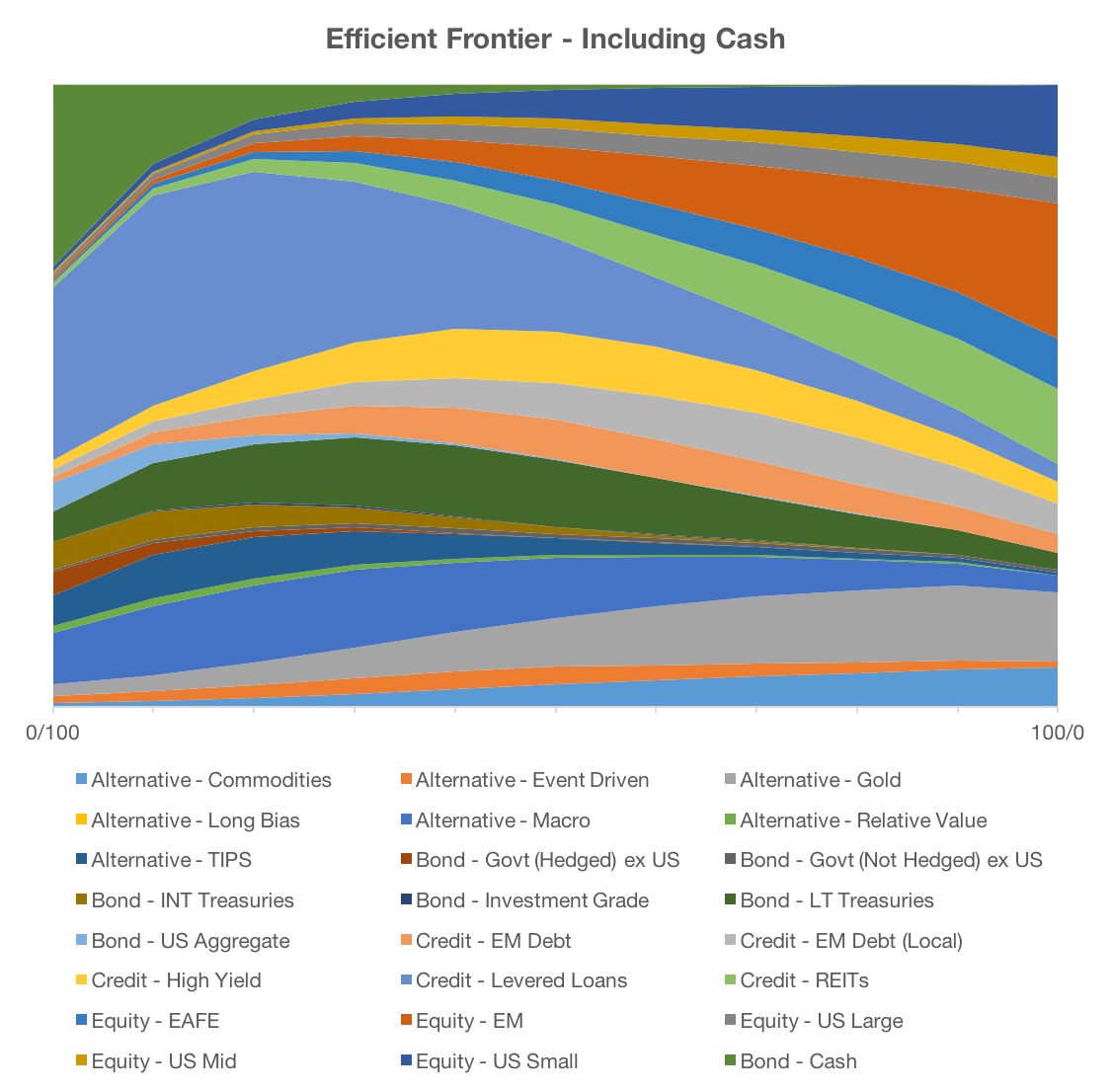

First, we will build the efficient frontier assuming long-only exposures with no cash or leverage permitted.

Second, we will build the efficient frontier assuming long-only exposures and no leverage, but allowing cash to be utilized.

It is worth noting that while above we were discussing barbelling cash with the Sharpe optimal portfolio, in theory by introducing cash as a potential asset class, we should achieve the same results for portfolios with a risk level below the risk level of the Sharpe optimal portfolio.

Note: In effort to account for parameter uncertainty in the capital market assumptions, our optimization process will use a simulation-based approach. This tends to lead to smoother asset allocation profiles over the frontier. Furthermore, while we take steps to account for parameter uncertainty, this research assumes that the J.P. Morgan outlook is directionally correct. Results could be meaningfully different if your views on risk and return deviate significantly from those presented by J.P. Morgan.

Below we present our results for the first frontier (long-only, no cash, no leverage):

Source: Capital market assumptions from J.P. Morgan. Optimization performed by Newfound Research using a simulation-based process to account for parameter uncertainty. Certain asset classes listed in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions were not considered because they were either (i) redundant due to other asset classes that were included or (ii) difficult to access outside of private or non-liquid investment vehicles.

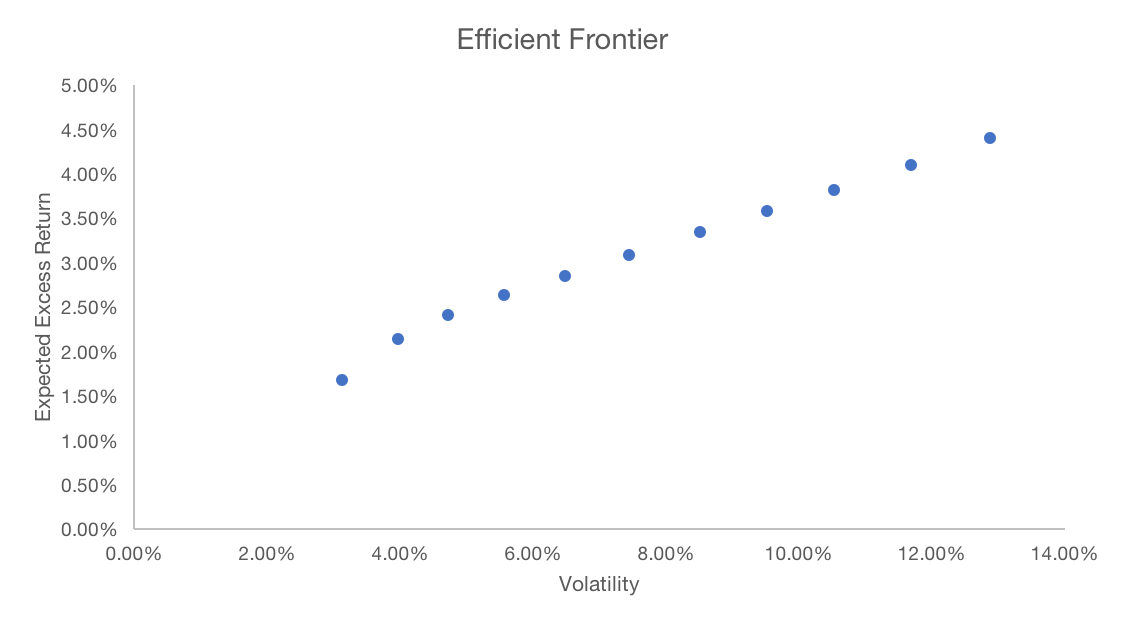

Transforming these portfolios into a risk-return frontier:

Source: Capital market assumptions from J.P. Morgan. Optimization performed by Newfound Research using a simulation-based process to account for parameter uncertainty. Certain asset classes listed in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions were not considered because they were either (i) redundant due to other asset classes that were included or (ii) difficult to access outside of private or non-liquid investment vehicles.

Further calculations show that the Sharpe Ratio increases from 0.53 to 0.54 in the leftmost (least risky) portion of the frontier, only to then decline to 0.34 at the far right (most risky) portion of the frontier.

This tells us that in our current environment, the Sharpe optimal portfolio is highly conservative. Risky assets, quite simply, are not offering a whole lot of expected bang for the risk buck.

Note: Much like we showed for the 2016 capital market assumptions, the 2017 assumptions still imply a large overweight towards credit assets like Bank Loans, High Yield Bonds, EM Debt (both USD and local currency), and REITs. If you are interested in seeing how we implement exposures like these in a portfolio, you can explore our model research portfolios. Or if you are interested in a strategy to access these asset classes, please see our Multi-Asset Income strategy.

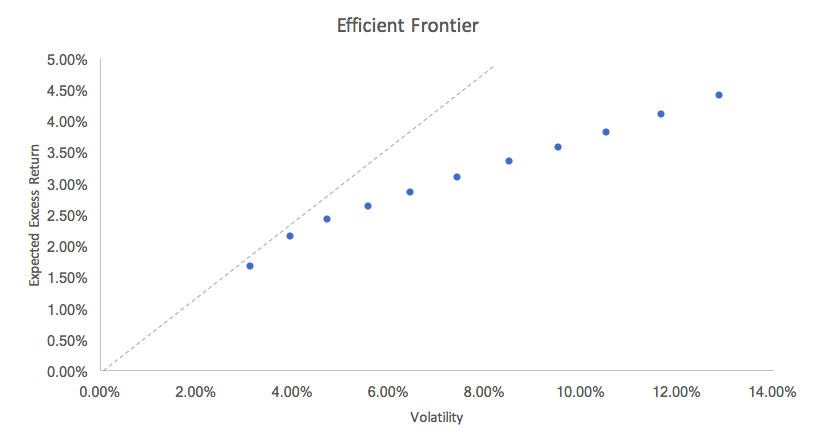

The implication of the highest Sharpe ratios being found in the most conservative portfolios is that even before we perform the optimizations that include cash, we can likely guess the result: cash will really only help in hyper conservative portfolios. Consider that in today’s environment, the capital allocation line will look something like this:

Source: Capital market assumptions from J.P. Morgan. Optimization performed by Newfound Research using a simulation-based process to account for parameter uncertainty. Certain asset classes listed in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions were not considered because they were either (i) redundant due to other asset classes that were included or (ii) difficult to access outside of private or non-liquid investment vehicles.

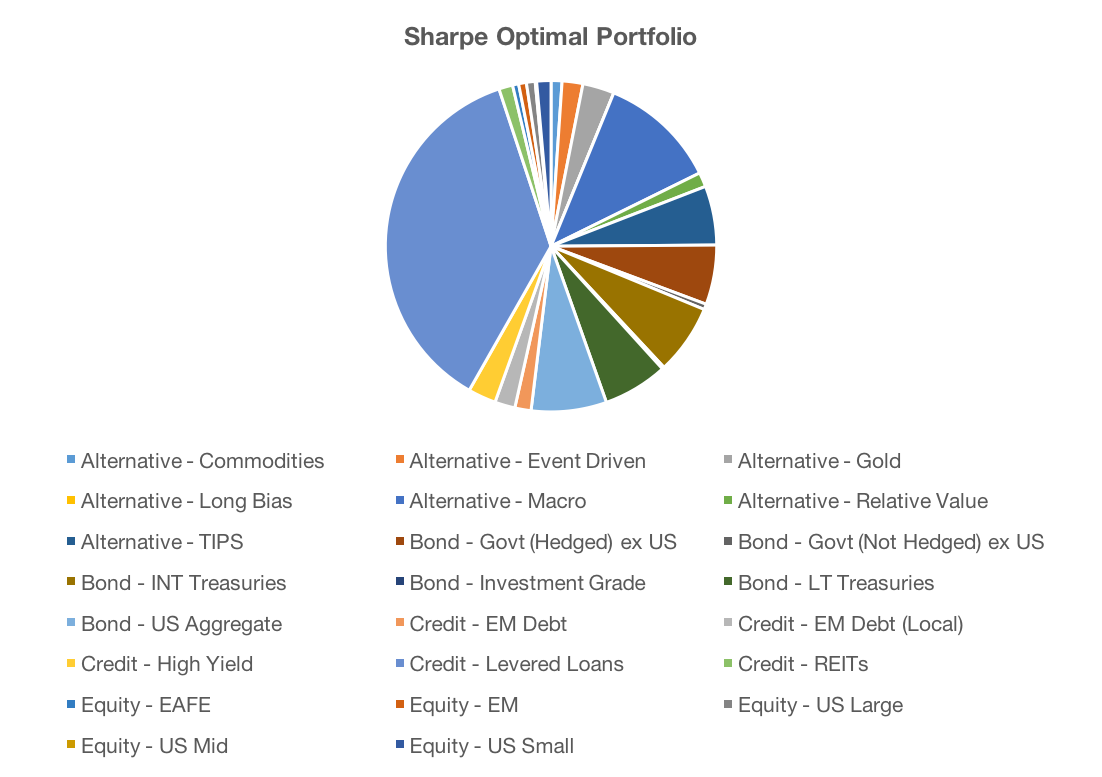

Explicitly solving for the Sharpe optimal portfolio, we see that it is highly conservative in nature (depending, of course, on your definition of “conservative”):

Source: Capital market assumptions from J.P. Morgan. Optimization performed by Newfound Research using a simulation-based process to account for parameter uncertainty. Certain asset classes listed in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions were not considered because they were either (i) redundant due to other asset classes that were included or (ii) difficult to access outside of private or non-liquid investment vehicles.

The volatility profile of this portfolio? Just north of 4%. For a point of comparison, in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions, U.S. aggregate bonds are expected to have a volatility profile of 3.5%. The expected excess return of the portfolio? Just north of 2%.

Given this framework of capital market assumptions, the Sharpe optimal portfolio finds itself in such a conservative profile (similar to a 10/90 style portfolio), buffering in cash will likely provide little advantage.

Indeed, when we perform the actual optimization that includes cash as an explicit asset class, we can indeed see that our guess is accurate: cash really only finds a roll in the lowest risk profiles.

Source: Capital market assumptions from J.P. Morgan. Optimization performed by Newfound Research using a simulation-based process to account for parameter uncertainty. Certain asset classes listed in J.P. Morgan’s capital market assumptions were not considered because they were either (i) redundant due to other asset classes that were included or (ii) difficult to access outside of private or non-liquid investment vehicles.

What we find is that in the most conservative portfolios, the allocation to cash is nearly 30%, with a reduction in International Government Bonds (Hedged), U.S. Aggregate Bonds, and Levered Loans.

By in large, however, the majority of capital that moved towards cash was from International Government Bonds (Hedged), which J.P. Morgan has as being the asset class with the closest risk/return profile to cash. In other words, it appears that in lieu of cash in the first optimization, the process sought out the asset class that looked the most like cash.

Conclusion

Portfolio theory tells us that investors may be doing themselves a significant disservice by not considering the use of leverage and cash within their portfolios.

While leverage introduces operational hurdles, the aversion to cash appears to be merely behavioral. This behavioral bias may be worth combatting, as avoiding cash may be doing a considerable disservice to conservative investors who may be much better off with a blended portfolio of high-risk assets and cash.

To test this theory, we utilized J.P. Morgan’s recently published 2017 capital market assumptions, running an optimization process first without cash, then introducing cash as a potential asset.

We find that in today’s market environment, cash adds little value except in the most extreme cases, as the current Sharpe optimal portfolio is highly conservative in nature.

Nevertheless, we believe that should we return to a more normalized interest rate environment, or should the expected returns of risky assets increase, the value of cash as a strategic asset may also increase considerably.

Copyright © Newfound Research