by Carl Tannenbaum, Asha Bangalore, Northern Trust

SUMMARY

- The View from Far Away

- Will Bank Deregulation Help U.S. Growth?

Many years ago, during one of my first trips to Australia, I met a man who observed that traveling is all about meeting people. I didn’t understand his message at first; when I was away from home, I was primarily interested in local sights, local sounds, and the smells that came from local kitchens.

But over time, I have come to embrace his meaning. Encounters with local residents provide a rich window into the soul of a place as well as a perspective on ourselves that we might not get at home. Both were offered in copious quantities during my visit last week, just after the U.S. election, to New Zealand and Australia.

The two countries are more than 6,000 miles from the west coast of the United States, and a world apart economically. Nonetheless, the events of November 8 (November 9 down there) were closely followed by everyone from investors to schoolchildren. There was a certain level of disbelief at the outcome that has since given way to concerned calculus.

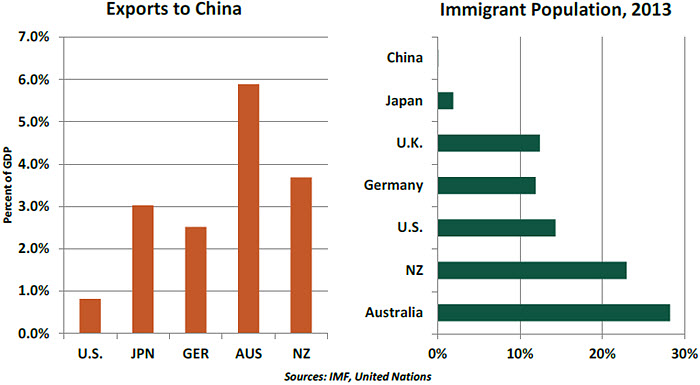

One client summed it up best: the region may be torn between its biggest ally (the United States) and its biggest trading partner (China). Both Australia and New Zealand sell significant amounts to China, and both would therefore be vulnerable to any threat to the pace of Chinese economic growth. On one hand, the prospect of a new U.S. infrastructure program would be beneficial; Australia’s mines supply minerals used by China to make steel and cement.

On the other hand, the prospect of heightened tariffs, domestic content requirements and other trade restrictions that the U.S. administration might enact is a significant source of anxiety in the region. The first order effects would be challenging enough (China might be at risk for a hard economic landing), but commenters noted that China would hardly sit still if America acted. The situation could escalate quickly to include commercial, financial and strategic consequences that would harm both the antagonists and their economic partners.

As we discussed in our post-election analysis, it is not immediately clear what benefit the United States would derive from instigating a trade battle with China. If a 45% tariff were implemented, importers would either have to pass along the surcharge to customers or find alternative sources (which could easily be more expensive). Either way, U.S. prices would rise; this would have a regressive impact, hindering those of modest means disproportionately.

As we discussed in our post-election analysis, it is not immediately clear what benefit the United States would derive from instigating a trade battle with China. If a 45% tariff were implemented, importers would either have to pass along the surcharge to customers or find alternative sources (which could easily be more expensive). Either way, U.S. prices would rise; this would have a regressive impact, hindering those of modest means disproportionately.

Some have expressed hope that protection would lead to a renaissance for U.S. manufacturing workers. But this could take time; American capacity in many industries is limited, and aged. Retaliatory measures from China or others could hinder American farmers and American corporations, resulting in an offset to any factory jobs gained. The ultimate outcome of the contretemps would be very uncertain.

Australia and New Zealand rank among the world’s most popular destinations for immigration. You see it in the streets and in the statistics; steady growth in the labor force is among the reasons that Australia hasn’t endured a recession in 25 years. Residents of Australia and New Zealand have the same anxieties about newcomers that citizens of other nations do; an Australian proposal to limit certain work visas was being debated while I was there. But one does not encounter the depth of anti-immigrant sentiment that is present in the United States and Europe.

Australia and New Zealand have small, open economies for which international commerce is essential. The growing trend toward economic nationalism threatens the business model they have embraced. The wish often expressed in conversations was that harsh rhetoric on globalization would give way to measured engagement. Of course, this may not satisfy President-elect Trump and his supporters.

After a busy week exchanging views and concerns, it was nice to take refuge in the Mornington Peninsula and the Yarra river valley on the weekend. And it was fun to invade the kitchens of two families to indulge my passion for cooking. The sights and smells were wonderful, but it was the connection with people that made the trip special.

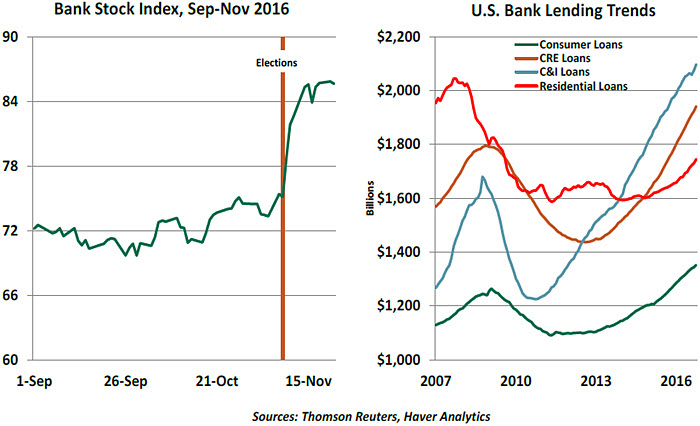

Re-De-Regulating Ahead

U.S. bank stocks rallied after the outcome of the U.S. election, partly in anticipation of reduced bank regulation. A series of new bank regulations were put in place after the Great Recession, and some think that these strictures have hampered bank lending activity and held back economic growth. If this claim is true, the new U.S. administration’s platform to dismantle major pieces of banking law could be viewed bullishly. But it is not clear that rolling back regulation or dialing back bank supervision will add measurably to the rate of expansion.

In general, the goal of the regulatory framework is to ensure safety and soundness of the financial system, maintain adequate capital of banking organizations, and to protect consumers from improper financial practices. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (DFA) expanded requirements in each of these areas. This key legislation is what the new administration aims to dismantle.

The Trump campaign platform is short on details, but Jeb Hensarling (currently the Chairman of the House Financial Service Committee, and on the short list to become the new U.S. Treasury secretary) introduced The Financial Choice Act (FCA) earlier this year, which may foreshadow how DFA will fare under the new regime. The impetus for the FCA stems from the belief that financial regulation has become complex and detrimental to growth.

The interconnectedness of non-bank financial institutions with the banking sector and their capacity to destabilize the U.S. economy was visible in the 2008 financial crisis, and oversight gaps were identified. The DFA was designed to address these gaps by identifying “systematically important” institutions (SIFIs) through its 15-member Financial Stability Oversight Council.

The interconnectedness of non-bank financial institutions with the banking sector and their capacity to destabilize the U.S. economy was visible in the 2008 financial crisis, and oversight gaps were identified. The DFA was designed to address these gaps by identifying “systematically important” institutions (SIFIs) through its 15-member Financial Stability Oversight Council.

SIFIs can be any kind of financial firm, raising the potential of additional oversight to insurers, asset managers, and others. The FCA would retroactively repeal the authority of this council to designate systematically important institutions.

The DFA also established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to protect consumers and educate them about financial products such as mortgages and credit cards. Its activities included investigating consumer complaints and identifying risks. CFPB rules govern banks, credit unions, and non-bank financial institutions offering consumer financial products. The FCA aims to change both name of the CFPB and its function. The new bureau would have a dual mission of consumer protection and competitive markets, which most assume would result in lighter regulation. Instead of a single director, a five-member committee would lead the agency.

The DFA set up the Volcker rule that limits deposit-taking banks from engaging in risky activities and restricts the types of relationships they may cultivate with hedge funds and private equity funds. The FCA would repeal these provisions.

The DFA has had a significant impact on the financial services industry. Financial institutions have increased payrolls for staff dedicated to following the rules set out in the DFA, including the annual stress testing exercise of banks. Complaints from community banks about regulatory costs are noteworthy. Loan underwriting standards have changed from the pre-crisis period, which can be viewed as both positive and negative.

The DFA has had a significant impact on the financial services industry. Financial institutions have increased payrolls for staff dedicated to following the rules set out in the DFA, including the annual stress testing exercise of banks. Complaints from community banks about regulatory costs are noteworthy. Loan underwriting standards have changed from the pre-crisis period, which can be viewed as both positive and negative.

There is a fundamental change in capital requirements following the passage of the DFA. Banks hold more capital, reducing the vulnerability of the financial system. The systemically important institutions are writing “living wills’ as part of regulation related to the DFA. Proponents herald reduced risk of financial contagion, and the incentive for the biggest banks to get smaller. Detractors suggest that if a new crisis were to arise, we might still see institutions and markets under significant stress.

If direct regulatory costs were punitive, credit expansion would be adversely affected. But bank lending continues to advance and support economic activity. Business loans, commercial real estate loans, mortgage loans and consumer loans have each posted meaningful gains in the current expansion. And if they have been hindered in any way, it is more likely the result of a desire for balance sheet repair and deleveraging among consumers and businesses.

One does not have to look far into the past to find examples of financial misbehavior and potential threats to the stability of the financial system. (See: Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank.) While there may certainly be opportunities for mid-course correction in post-crisis legislation, rolling regulation back to where it stood ten years ago would be dangerously short-sighted.

Copyright © Northern Trust