by Carl Tannenbaum, Asha Bangalore, Northern Trust

SUMMARY

- Beware of Larger for Longer

- The Case for Fiscal Expansion

- Emerging Market Central Banks Have Grown the Right Way

When our first child arrived, we knew the first months would be chaotic. Once the baby’s cycle stabilized, we told ourselves, we’d be able to get back to normal. Well, it took longer than we thought; more than 25 years. But we’re finally close to returning to our pre-child equilibrium.

Business cycles were disrupted by the chaos of 2008. To respond, central banks have extended themselves in an effort to reach a more settled equilibrium. Conventional wisdom was that central banks would eventually return to normal by unwinding these extraordinary measures. Yet some scholars are recommending a new approach to monetary strategy that keeps balance sheets much larger for much longer. This approach, however, comes with significant financial and political risks, and its efficacy is far from clear. Before central banks lock up assets and throw away the key, they should reflect very carefully on potential consequences.

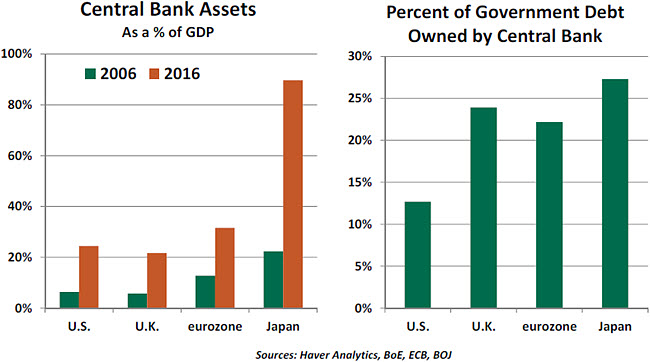

Monetary authorities in the developed world have added significantly to their balance sheets in the last decade through quantitative easing (QE) programs of various sizes and styles. The U.S. Federal Reserve ceased new asset purchases almost two years ago, but the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the Bank of England and the European Central Bank (ECB) are all still expanding their QE efforts.

Committing to a QE program is essential to shaping market psychology. If investors anticipate that the effort is transitory, it won’t have the desired effect. Nonetheless, the widespread belief has been that central bank balance sheets would eventually recede to pre-crisis levels. In her keynote remarks at this year’s annual Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Fed Chair Janet Yellen reiterated the Fed’s intent to follow this course.

But during a subsequent panel in the symposium, Jeremy Stein, a former membfer of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, proposed an alternative strategy. He suggested central banks should keep large balance sheets long after interest rates have moved away from zero. Stein argued that such a policy could curb the tendency of financial companies to fund short and lend long, a strategy that leaves them (and the financial system) vulnerable to liquidity and interest-rate risk.

Ben Bernanke, who attended the Jackson Hole symposium for the first time since leaving the Fed, seemed to endorse the maintenance of large balance sheets in a recent blog. Bernanke notes that high levels of excess reserves held by banks have changed the dynamic of managing interest rates at both the short and the long ends of the yield curve. Keeping the balance sheet large, he argues, could improve the transmission of monetary policy to the broad economy.

There are, however, several reasons why central banks should be very cautious about turning unconventional policy into business as usual.

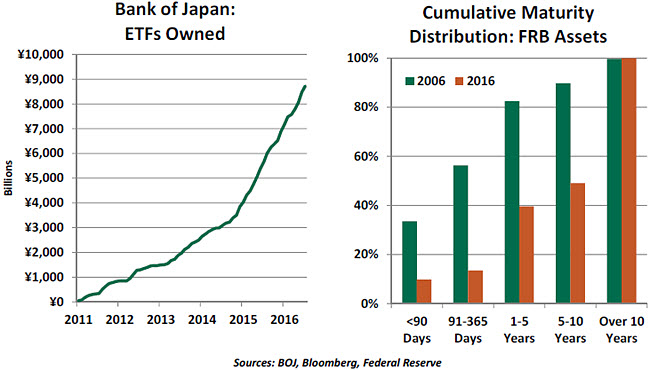

First, it seems that central banks are extending themselves into areas that had been the province of private-sector financial institutions. They have become primary creditors by investing in non-sovereign debt, and some have become investors by extending into equity markets. The BoJ, for instance, holds more than half the total volume of Japan’s outstanding exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Central bank balance sheets typically have short-term funding, but most have lengthened the maturity of their assets significantly over the past decade. The printing press is the ultimate safeguard against the risk presented by this mismatch, but using it might ease credit just as policy should become more restrictive.

New capital and liquidity requirements have reduced the level of credit extension and maturity transformation among private-sector financial firms. As central banks move to take up some of the slack, their balance sheets are exposed to heightened levels of credit, market and (in some cases) currency risk. It is not clear that central banks have the infrastructure to measure or manage these risks to the same standard that regulators require from private-sector firms.

Losses taken on those positions can be rationalized (hopefully) by the better economic outcomes that often result from quantitative easing. But losses invite additional political scrutiny, which could ultimately erode central bank independence. The choice of which assets to buy may favor some sectors or countries over others, which might bring the central bank additional criticism.

Second, central bank asset ownership has a profound effect on pricing and liquidity in markets. QE programs mandate a certain scale of asset purchases, regardless of risk or return. Private investors in those markets must live with uncertainty surrounding the amount and composition of the central bank’s portfolio. That may hinder financial stability, not help it.

Finally, if the central bank does hold a big balance sheet permanently while the sovereign carries high levels of debt (which is currently the case in most developed countries), it raises questions about whether the debt is being monetized. Some see the outlines of covert “helicopter money” strategies in some markets, Japan being the primary example.

I appreciate that large central bank asset holdings aid the conduct of monetary policy. But I haven’t concluded that markets or private financial institutions have proven incapable of fulfilling their traditional roles as intermediaries. If monetary authorities want cleaner translations of their actions into results, some modest regulatory relief might be a better path forward. That would allow monetary and supervisory policy to reach a productive new normal.

The Danger of Deleveraging

There is a common thread running through discussions about how to stimulate economic growth in advanced economies. Surprisingly, it is about fiscal policy. Central bank rhetoric now typically mentions the limitations of monetary policy and the need for fiscal policy to work as a constructive partner. Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, reiterated this view at a press conference on September 8.

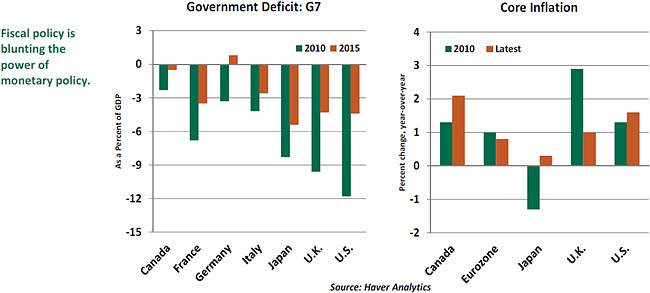

The ECB and the BoJ are currently making monthly asset purchases of €80 billion and ¥80 trillion, respectively, to stimulate economic activity. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy, stands at 0.8% and 0.3% in the eurozone and Japan, respectively. Low oil prices explain a large part of the subdued overall inflation trends. Both institutions aim to meet the 2.0% inflation goal in the quarters ahead. The United States is in a different situation, with core inflation closer to the target, but reaching that target has proven challenging.

The environment under which monetary policy works is critical for central bank policy to achieve price stability and full employment targets. A central bank’s monetary policy actions can support demand, stabilize prices and manage inflation expectations. But fiscal policy influences the speed with which the economy can return to its potential capacity. Monetary policy is more effective if fiscal policy is working in the same direction.

At the Jackson Hole symposium, Nobel Prize winner Christopher Sims described the importance of fiscal policy to monetary policy effectiveness. His argument ran as follows: Government debt is one of the many assets in private-sector portfolios. If fiscal austerity implies a lower government deficit in the future, government securities will be seen in a positive light, firms will change their asset allocation to favor government debt and investment expenditures will suffer and reduce aggregate demand. The solution Sims proposed is expansionary fiscal policy to maintain aggregate demand.

Within the context of quantitative easing programs of the advanced economies, fiscal policy has not always worked in tandem with monetary policy. In the eurozone, fiscal policy was contractionary after the debt crisis of 2010. Fiscal consolidation through tax increases prevented a strong recovery. Germany has been in a favorable fiscal position, but given the nation’s anxiety over its total debt levels, the government has been unwilling to use fiscal policy to spur growth.

Japan’s most recent experience with the monetary and fiscal policy mix also illustrates Sims’ argument. The BoJ undertook aggressive monetary policy easing beginning in 2013, but imposed a consumption tax in 2014, defeating the purpose of monetary policy. Japan’s Inflation remains below target and growth is lackluster.

The BoJ will take a comprehensive look at monetary policy at its meeting later this month. BoJ Governor Kuroda indicated in a speech earlier in the week that one of the factors holding down inflation in Japan is “greater-than-expected downward pressure after the consumption tax increase.” The Abe administration, in fact, postponed the second leg of consumption tax hike to 2019; it was originally planned for April 2017.

The pace and time span of economic recovery has lasting macroeconomic consequences. If the fiscal and monetary policy mix are unfavorable, real gross domestic product will continue to remain below potential capacity, and the unemployment rate will fail to shrink rapidly. Without coordination of monetary and fiscal policy, fiscal policy will take away what central banks offer.

Central Bank Growth Isn’t All Bad

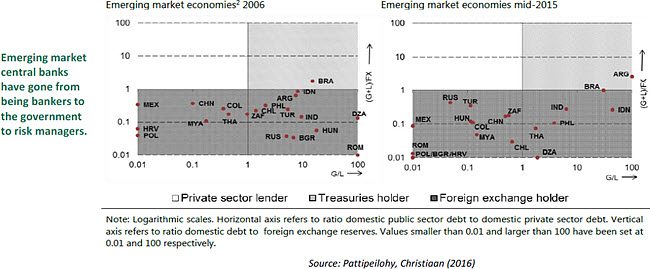

Even as the bulging size of central bank balance sheets in the developed world has come under (mostly unfavorable) scrutiny, the increase in emerging market central bank balance sheets has attracted relatively little attention.

It has been a fairly benign expansion, driven by a buildup of foreign exchange reserves (precautionary savings and resources for exchange rate intervention) and lending to commercial banks to mitigate financial instability. The following set of graphs on the composition of emerging market central bank assets illustrates this.

A rightward shift along the horizontal axis reflects increases in lending to government (G) versus the private sector (L), while a bottom-to-top shift along the vertical axis reflects an increase in the holding of domestic assets (G+L) relative to foreign assets (FX). Most emerging markets lie in the bottom left quadrant, indicating the dominance of foreign and private assets on their balance sheets.

This signifies a marked change in the role of these central bankers, who have essentially gone from being “bankers to the government” to risk managers. Until a couple of decades ago, it wasn’t unusual for central banks in developing economies to monetize a sizable chunk of the fiscal deficit — basically printing money to finance government spending. However, by the end of the 20th century, most major economies had passed some kind of legislation prohibiting or restricting direct central bank lending to the government. Emerging markets’ embrace of economic orthodoxy was a bid to attract global capital and business by escaping a history of high inflation, currency fluctuations and economic volatility.

This stands in stark contrast to the ongoing policy debates in developed economies. Politically unable to confront deep seated structural problems, countries either seem to be moving towards populism, or policy makers are being forced to explore unorthodox options. This may be one area where emerging markets can teach their more mature relatives a lesson.

Copyright © Northern Trust